The Myths Were Right: God Created the World From Sound – Joachim-Ernst Berendt

HAFIZ, the great Sufi poet of fourteenth-century Persia, told the following legend:

God made a statue of clay in His own image, and asked the Soul to enter into it; but the Soul refused to be imprisoned, for Its nature is to fly about freely and not to be limited and bound to any sort of capacity. The Soul did not wish in the least to enter into this prison. Then God asked the angels to play their Music, and as the angels played the Soul was moved to ecstasy, in order to make the Music more clear to Itself, It entered his body.

Hafiz is said to have added: "People say that the Soul, upon hearing that Song, entered the body; but in reality the Soul Itself was the Song." And Hazrat Inayat Khan comments:

This is a beautiful legend, and much more so to its mystery. The interpretation of this legend explains to us two great laws. One is that freedom is the nature of the Soul, and for the Soul the whole tragedy of life is the absence of that freedom which belongs to Its original nature; and the next mystery is that this legend reveals to us that the only reason why the Soul entered the body of clay or matter is to experience the Music of life, and to make this Music clear to Itself.

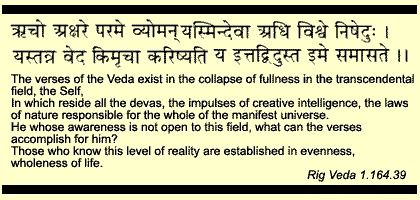

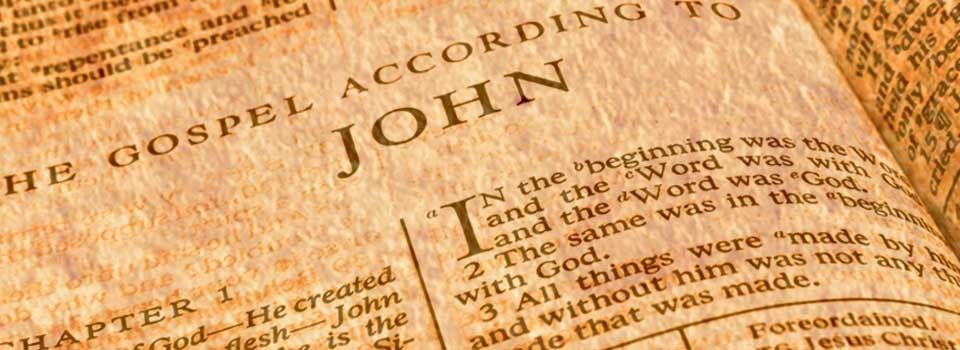

In the beginning was the Sound, the Sound as Logos. If you remember, God's command "Let there be…" at the beginning of the biblical story of creation was first tone and sound. For the Sufis, the mystics of Islam, this is the core of things: God created the world from sound.

Many of the world's cultures have passed down sagas and myths, legends and tales in which the world has its origin in sound, from the Aztecs to the Eskimos, from the Persians to the Indians and the Malayans. In fact, there is such a wealth of these myths that only a few can be mentioned here (in fact, others have been mentioned in earlier chapters).

In Egypt, the "singing sun" created the world with its "cry of light." In ancient Egyptian scripture it is written that through "the tongue of the creator…all Gods and everything in existence were born…Atum and everything divine manifest themselves in the thought of the heart and in the sound of the tongue." The symbol for "tongue" in Egyptian hieroglyphics can also mean "word"; it is the tongue that forms the sound that in turn carries the word. Thus the flowing transition from mantric sound to spoken word (which I spoke of in chapters 2 and 3) can still be detected in the early stages of the art of writing. In another Egyptian tradition, Thoth, the god of the word and of scripture, of dance and music, creates the world by repeating his "laughing word" seven times.

Here is another version:

Inaudible and motionless, says the mythology of the Aztecs of Mexico, was the creator. An iceberg! Silent as stone. One day, however, he cast off the iceberg and broke his silence, as he was no longer able to resist his deepest wish to create the world and mankind. He sang: "This world shall be!" And the world came into being.

For almost all nations of the world, music and the divine are closely connected. Many ragas (the scales of Indian music) have a religious meaning; some of them refer directly to certain gods and their reincarnations. It is similar with the rhythms of most African cultures. The rituals of the West African Yoruba, for instance, have remained alive in Brazil in the widespread Macumba and Candomblé cults, their music forming the basis of the Brazilian samba and carnival rhythms. Even today, many Brazilian drummers and percussionists — even those working in television and recording studios — know which rhythm belongs to which "god." That's the way they put it: The rhythm "belongs" to a god. In the mid-sixties, when I was recording the Brazilian percussionists Rubens and Georghingho, suddenly they both began to call out the names of those deities who were being evoked by the particular rhythms they were drumming: first Xango, the great god of thunder and war, the Jupiter in the celestial spheres of the Yoruba; then Nana, the goddess of love, whose name was pronounced by Georghingho with particular tenderness; after that Ogumthe god of the jungles and forests; and finally Omulu, the god of the ill ( who Rubens called To-to). I was shocked by the intensity with which they did this. Everyone in the studio sensed that it was important to them. It had to happen right then and there. It was a ritual, albeit a miniature one, almost like the cipher of a Macumba rite, which they needed right now, at least as a cipher. After that, they swiftly proceeded with the recording work like the professionals they are, although in a much more relaxed manner.

In India, the Vedic creator-god Prajapati was himself hymn and song. "The rhythms," it is said, "are his limbs," the limbs, that is, of the god who created the world. "The first sacrificial offerings and the first gods were meters, and the seven archfathers of mankind were also rhythms." In the Aitareya-Upanishad, rhythms are compared to horses: As one travels with horses or oxen to reach a terrestrial goal, one needs rhythms and meters to reach heavenly goals. Of Brahma it is said: "He meditated a hundred thousand years, and the result of his meditation was the creation of sound and music."

Thus the first act of creation was the creation of sound. Everything else came after and through it.

Plato, in his famous dialogue Timaeus, tells that the creator constructed the world-soul (which to Plato means the idea of the cosmos) according to musical intervals and proportions. And with his music, the divine singer Orpheus was able to cast formless matter into form (which for the Greeks meant; into structured beauty).

In Polynesia, on Samoa, Tahiti, Hawaii, there were originally — before all other deities were added — three great gods. The three of them (another trinity!) — Tane, Tu, and Rongo (Lono on Hawaii) — created the world, and all three have to do with sound. Tane's symbol was the horn, Tu's the triton shell, and Rongo was the actual god of sound and tone who (consequently!) despised human sacrifice and was considered the mildest and best loved of the gods.

In the thinking of many cultures of the world, it was God ( or several gods ) who originally created music and somehow handed it down to humankind, usually by way of an especially gifted medium, for instance, through Orpheus in ancient Greece. For the African Ibuzo tribe in Nigeria, this medium was a singer called Orgadié. Having lost his way in the jungle, he heard the music of the spirits and gods of the trees there. They were making music on twigs and branches and stems, on blades of grass, on the tree leaves and vines. Hidden in the bush, Orgadié listened, trying not to forget anything, and later brought it all back home to his village.

Following the account of an old Brahman priest, Swiss ethnologists Theo Meier and Ernst Schlager tell the following Balinese legend:

Lord Shiva once sat on Mount Meru…Out of the distance, he heard soft tones of a kind he had never heard before. He summoned Narada, the wise man, sending him to the Himalayan hermitages to find out where the tones were coming from. Narada went on his way and finally reached the hermitage of the sage Dereda. There the tones sounded stronger. He entered the hermitage. The hermit told him that the wondrous tones were, indeed, coming from his land. The hermitage was surrounded by a bamboo grove. Dereda had made holes in the bamboo canes to tie them together. Now, when the wind blew through the holes, the most diverse tones would be sounded. Dereda said he had been so delighted by this discovery that he had tied a bunch of bamboo canes with holes together and hung them up in a tree (creating a sound box like an aeolian harp), for no other reason than to produce a continual, pleasant sound.

Narada returned to Lord Shiva to report to him what he had learned. Shiva decided that these bamboo harps were to form the basis of all music on Bali, because humans had thereby received the ability to pay their reverence to the gods and to please them in a new way. Whereas music had been in a state of chaos before, Lord Shiva provided it with an orderly system.

A particularly moving legend about the way sound, music, and dance bring order and harmony to the chaos resulting from the creation of the world comes from Japan. It relates how Amaterasu, the sun goddess, sought recluse in a cave. There was no sunlight, everything was dark and desolate. Then Izanagi, the creator-god, took six giant bows and tied them together, creating the first harp. On it he played wonderful melodies. Lured by them, the charming nymph Ame no Uzume appeared. Enraptured by the harp music, she began to dance — and finally to sing. Amaterasu, the sun goddess, wanted to better hear the music that had reached her ear from far away. For this reason she glanced outside her cave — and in the same moment the world was showered with light. The sun came out to be seen and felt, flowers and plants and trees began to grow. Fish and birds, animals and humans entered the light-filled earth. The gods however, decided to cultivate music and dance so that the sun goddess would never return to her cave again, because they knew: It was the sun that had produced life, but without the harp music of the six great bows and without the singing of the nymph Ame no Uzume, the sun goddess Amaterasu would never have taken up her place on the heavenly throne. She would have stayed in her cave for all eternity. So it was sound, music, and dance, with which the world began.

Since God created the world from sound, and since sound and music were given to humankind by the god(s), you will find that in most cultures it is music whose sound discloses God's will and the deepest secrets of creation to man. In China, there is the story of the great Taoist Huan Yi, who was not only an enlightened sage but also a gifted flute player. A Taoist dignitary had heard that Huan Yi would come to that particular area on his travels. The dignitary sent an envoy to Huan Yi, asking him to pay a visit and share his wisdom with him. Then Huan Yi "descended from his coach, seated himself on a chair, and played the flute three times. Thereupon he entered the coach again and drove off." The two did not exchange a single word, but legend has it that the dignitary was an initiate from that time on.

There is also a Zen version of this story. When Kakua, one of the early pioneers of Buddhism in Japan, returned from a voyage to China, the emporer asked him to tell about all the wisdom he had brought back from China. Kakua took out his shakuhachi (bamboo flute), played a melody, took a polite bow, and walked off. The emporer, however, was enlightened in that moment.

There are certain ceremonial rites in Islam that do not permit any kind of music. Hazrat Inayat Khan tells of a wonderful experience from the lifetime of the saintly Khwaja of Ajmer. To visit this saint, Khwaja Abdul Qadir Jilani, a great master who was also an advanced Soul, came to him from Baghdad. Now the saint was very strict in his religious observance and would not have any music. His guest, of course, wanting to respect this rule, had to sacrifice his daily musical practice. He did continue his daily meditation routine, however. But when he started to meditate, the Music began to sound by Itself, and everybody listened. It continued this way for some days. Qadir Jilani did not touch his instrument, but whenever he started to meditate, the music began. Hazrat Inayat Khan comments: "Music is meditation and meditation is music. The enlightenment which we can find in meditation we can experience in music, too."

There is another similar story, also told by Hazrat Inayat Khan, about the Mogul emporer Akbar and Tansen, a famous musician at his court:

The Emporer asked him, "Tell me, O great musician, who was your teacher?" He replied, "Your Majesty, my teacher is a very great musician, but more than that. I cannot call him 'musician,' I must call him 'music'!" The Emperor asked, "Can I hear him sing?" Tansen answered, "Perhaps, I mat try. But you cannot think of calling him here to court." The Emporer said, "Can I go to where he is?" The musician said, "His pride may revolt even there, thinking that he is to sing before a king." Akbar said, "Shall I go as your servant?" Tansen answered, "Yes, there is hope then." So both of them went up into the Himalayas, into the high mountains, where the sage had his temple of music in a cave, living with nature, in tune with Infinite. When they arrived the musician was on horseback and Akbar walking. The sage saw that the Emperor had humbled himself to come hear his music, and he was willing to sing for him. And when he felt in the mood for singing, he sang. And his singing was great; it was a psychic phenomenon and nothing else. It seemed as if all the trees and plants of the forest were vibrating; it was a song of the universe. The deep impression made upon Akbar and Tensen was more than they could stand; they went into a state of trance, of rest, of peace. And while they were in that state, the Master left the cave. When they opened their eyes he was not there. The Emporer said, "O, what a strange phenomenon! But where has the Master gone?" Tansen said, "You will never see him in this cave again, for once a man has got a taste of this, he will pursue it, even if it costs him his life. It is greater than anything in life."

When they were home again, the Emporer asked the musician one day, "Tell me what raga, what mode did your master sing?" Tansen told him the name of the raga, and sang it for him, but the Emporer was not content, saying, "Yes, it is the same music, but it is not the same spirit. Why is this?" The musician replied, "The reason is this, that while I sing before you, the Emporer of this country, my Master sings before God; that is the difference."

"Master of the tone" was the name given to a wise old man whom Alexandra David-Neel encountered in a remote monastery somewhere in the Himalayas near the Sino-Tibetan border. In a temple of the monastery, the old master (whose real name was Bönpo) played the chang,the ancient Tibetan cymbal whose edges are bent upward. All of a sudden, "an unearthly sound, similar to a confused screaming, shook the hall and pierced my brain." The peasants and escorts of the European voyagers cried out in horror — and there was not one among them who was not totally sure he had seen a fiery snake: "The snake came out of the chang when the Lama struck it," one of them said, and the others agreed with that. Afterwards, the Lama told the voyagers:

I am the master of the tone. With the tone, I can kill living things and revive dead things….All creatures, all things, even the seemingly lifeless ones, give off tones. Each being, each thing produces a special, characteristic tone which, however, changes as the states of the being or thing by which it is produced change. Why? Beings and things are conglomerations of smallest particles, the so-called rdul phra; they dance, and with their movements they produce tones.

This is what the teachings say: In the beginning was the wind. With its whirl, it created gjatams, the primordial forms and the prime base of the world. This wind sounded; thus it was the sound which formed matter. The sounding of these first gjatams brought forth further forms which, by virtue of their sounds, in turn created new shapes. That is by no means a tale from days long passed, it is still that way. The sound brings forth all forms and all beings. The sound is that through which we live.

To our Western mind, legends and myths hail from ancient times, but the only reason they do so is because we have banished them there. In reality, they are now. They have come into existence because people need them. The rationalist believes he can do without myths. He doesn't want to be made uncertain of his "belief" that the rational mind is omnipotent. But perhaps this, too, is part of the change of consciousness we are witnessing: Contemporary man has a need again for myths and mythical things. One indication of this is the worldwide success of such authors as J.R.R. Tolkien, the enthusiasm with which young people devour his books. And, of course, there is a mythical core in the better Western and fantasy films and comic strips. Some of them are pure myth.

In Tolkien's Silmarillion, sound plays a decisive role in crucial passages. In the very first pages of the book, the world begins with a "song." When the patriarch Ilúvatar assigns to the Ainur — the elves and forefathers of mankind — the "fair regions" of "the Void" as their place of residence, he says:

"Behold your music! . . . Of the theme that I have declared to you, I will now that ye make in harmony together a Great Music. And since I have kindled in you the Flame Imperishable, ye shall show forth your powers in adorning this theme, each with his own thoughts and devices, if he will. But I will sit and hearken, and be glad that through you great beauty has been wakened into song."

Then the voices of the Ainur, like unto harps and lutes, and pipes and trumpets, and viols and organs, and like unto countless choirs singing with words, began to fashion the theme of Ilúvatar to a great music; and a sound arose of endless interchanging melodies woven in harmony that passed beyond hearing into the depths and into the heights, and the places of the dwelling of Ilúvatar were filled to overflowing, and the music and the echo of the music went out into the Void, and it was not void. Never since have the Ainur made any music like this music, though it has been said that a greater still shall be made before Ilúvatar after the end of days. Then the themes of Ilúvatar shall be played aright, and take Being in the moment of their utterance, for all shall then understand fully his intent on their part, and each shall know the comprehension of each, and Ilúvatar shall give to their thoughts the secret fire, being well pleased.

In Tolkien's world, evil also manifests itself musically at first; in fact, in the end it is musical dissonance that causes dissonance in creation:

But now Ilúvatar sat and hearkened, and for a great while it seemed good to him, for in the music there were no flaws. But as the theme progressed, it came into the heart of Melkor to interweave matters of his own imagining that were not in not in accord with the theme of Ilúvatar; for he sought therein to increase the power and glory of the part assigned to himself….

Some of these thoughts he now wove into his music, and straightway discourse rose about him, and many that sang nigh him grew despondent, and their thought was disturbed and their music faltered; but some began to attune their music to his rather than to the thought which they had at first. Then the discord of Melkor spread ever wider, and the melodies which had been heard before foundered in a sea of turbulent sound. But Ilúvatar sat and hearkened until it seemed that about his throne there was a raging storm, as of dark waters that made war upon another in an endless wrath that would not be assuaged.

Another great author of modern myths is Michael Ende. His Momo relates the beautiful story of a "glittering pendulum" that brings forth ever new buds and blossoms and flowers, more and more beautiful with each swing of the pendulum. The actual force, however, that drives the "glittering pendulum" and the "shaft of light" beaming down from the dome of the heavenly vault, is a sound:

At first it reminded her of wind whistling in distant treetops, but the sound swelled until it resembled the roar of a waterfall or the thunder of waves breaking on a rocky shore.

More and more clearly, Momo perceived that this mighty sound consisted of innumerable notes whose constant changes of pitch were forever weaving different harmonies. It was music, yet it was also something else. All at once, she recognized it was the faraway music she had sometimes faintly heard while listening to the silence of a starry night.

But now, as the sound became ever clearer and more glorious, she sensed that it was the resonant shaft of light that summoned each bud from the dark depths of the lake and fashioned it into a flower of unique and inimitable beauty.

The longer she listened the more clearly she could make out individual voices — not human voices, but notes such as might have been given forth by gold and silver and every other precious metal in existence. And then, beyond them, as it were, voices of quite another kind made themselves heard, infinitely remote yet indescribably powerful. As they gained strength, Momo began to distinguish words uttered in a language she had never heard before but could nonetheless understand. The sun and moon and planets and stars were telling her their own, true names, and their names signified what they did and how they all combined to make each hour-lily flower and fade in turn.

Since God created the world from sound, all music is directed back to God and the gods. That is why all music, first and foremost, is praise of God. This idea can also be found in the music concepts of almost all cultures of the world.

Ancient Indian mythology says that "the carriage of the sun had a shaft consisting only of songs of praise." In the Rig-veda of ancient India, the primordial rhythm and the primal sounds are fused into a "rustling song of praise" that "encouraged creation to grow and prosper."

The most beautiful expression of this thought, however, has been created by those singers who stand at the outset of Christian and Jewish poetry (and music!): the psalmists. Thousands of years ago, in the four final hymns of the Psalms (from Pslam 147 to 150), they created the following verses, which have inspired musicians and composers (from John Sebastian Bach to Duke Ellington) time and time again in the course of centuries to musical settings filled with thanks and praise:

Sing unto the Lord a new song….

Let them praise his name in the dance: let them sing praises unto him with the timbrel and harp.

(Psalm 149)

Praise ye the Lord.

Praise God in his sanctuary: praise him in the firmament of his power.

Praise him for his mighty acts: praise him according to his excellent greatness.

Praise him with the sound of the trumpet: praise him with the psaltery and harp.

Praise him with the timbrel and dance: praise him with a stringed instrument and organs.

Praise him upon the loud cymbals: praise him upon the high sounding cymbals.

Let everything that hath breath praise the Lord. Praise ye the Lord

(Psalm 150)