Show Time – Phil Morimitsu

In the warmer months, t's often a habit of mine to take a walk after dinner. It gives me time to think, to contemplate on the ECK, and, oftentimes, to talk with the Mahanta. One night, I found myself walking farther than I usually did. I was in the downtown theater district, and one of the plays was just letting out. The previously silent street was suddenly bustling and jumping with people, fresh from having a good time. I could feel the vibrancy and light as the people burst out of the theater. I crossed the street to avoid the crowd and turned the corner to a more sedate street. Still, I could hear the laughing and talking of the people from the theater, and, somehow, it made me feel good. Perhaps the good times were rubbing off on me a bit.

The street I was on was dark — a back street, the unseen side of the brightly lit theater district, that nevertheless had to exist, just as the dark side of the moon must exist. There was one building among the deserted warehouses and closed-up shops that intrigued me the way forbidden caves will attract little boys. It was an old, abandoned theater — dead as a lump of cold, wet charcoal. The entranceway doors, once glass, were now just splintered sheets of plywood, and the box office, which had also long since lost its glass, was now serving as a trash bin for empty soft-drink cans and crumpled paper. One of the boarded-up entrance doors was open. The little boy in me was the only excuse or reason I can think of for wanting to go inside. Defying all logic, common sense, and fear that warns one of impending danger, I challenged myself and poked my head into the gaping maw, into the black cavernous lobby of the theater.

I must be out of my mind, I said to myself. But I said this as i stepped into the hallway. I waited for the tinge of warning that would well up in my stomach, but it didn't come. Instead, an unexpected peace came as I found myself — trying not to make any sounds — walking into the theater and up to the doors that led to the seats and finally the stage itself. Unlike the outside of the theater, which showed so many signs of deterioration, the inside was in much better shape. It was as if the last performance had been given only a few nights ago; I could still sense the same kind of joy and liveliness that I'd felt just a few minutes ago out on the street, as the crowd left that other theater. My eyes adjusted to the darkness, and I began to make out the rest of the theater's interior.

The seats were covered in soft, red velvet and were well padded. I moved to the back row and took a seat next to the aisle. As I looked at the barren stage and thought of its past, when it held the magical spell that was the world of theater and drama, the voice of Wah Z floated to me from behind.

"The real show is about to begin."

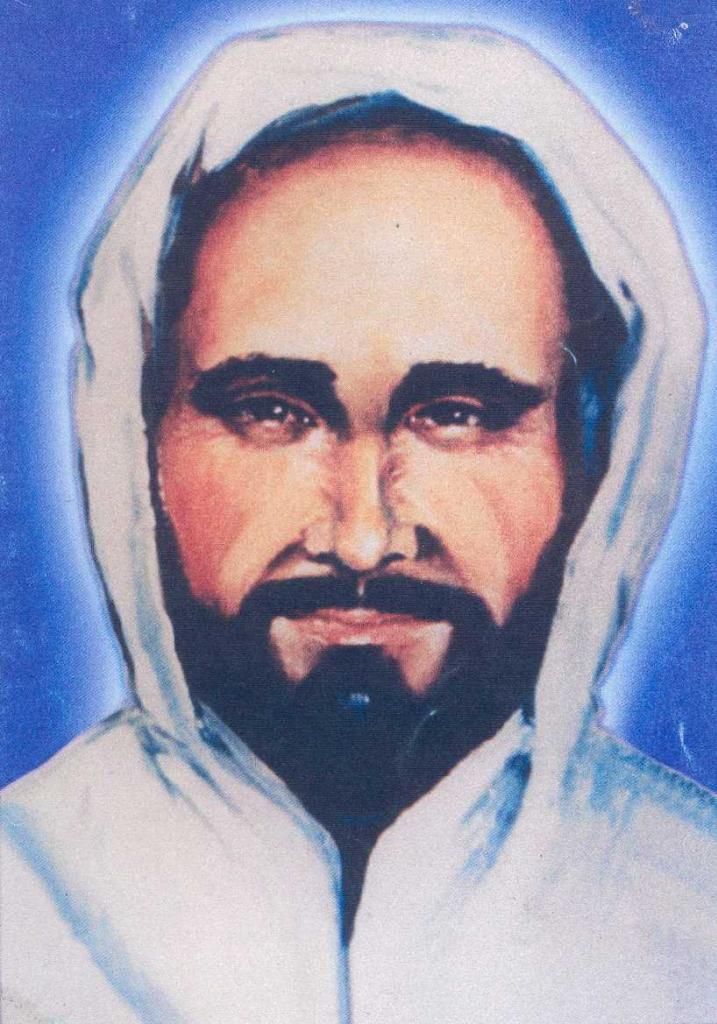

I turned to greet him and was surprised to see not only Wah Z, but also another man standing at the back. The man, about thirty-five or forty, was wearing a white cotton, hooded robe belted at the waist. His black hair was cut short, and he had a short beard and wide mouth with thin lips. His features were dark and swarthy; his eyes were black, which made them look deep and flashing. I guessed that he was Middle Eastern. He was about Wah Z's height, maybe a little shorter (five feet eight or nine inches), and lean. Wah Z introduced him to me.

"I'd like you to meet Sri Zadok of Judea," he said.

The man called Zadok held his hands together in front, near his chest, and bowed his head to me, eyes cast downward. There was a deep reverence about this being, a silent quality that seemed to go with his looks — that of a dark, mysterious figure from the ancient East. I'd known that Zadok was an Essene, from the time of Jesus Christ, and was reputed to have met and taught Jesus during the twenty some years the latter spent wandering and gathering knowledge around the world.

After allowing me a moment to visually take in the stranger, Wah Z spoke again, "Sri Zadok knows something of the theater. Perhaps this is why you were drawn to this place.

I looked at Sri Zadok, and he bowed his head once again, in that slow, reverent manner of the Middle East. But the way he bowed, I didn't get the feeling that he was doing it out of social habit, the way modern Westerners spit out greetings in a half-conscious manner, like, hi-how're-ya-pleased-ta-meet-cha. When he bowed his head, he exhibited genuine reverence and warm respect for me. Then he motioned to the stage, as if to request that I look at what was about to unfold. As I looked at the still empty stage, he began to speak in a low, soft voice.

"The theater, the stage, life in the streets of your metropolis — all are illusory. Yet they serve their purpose, for in their unreality, they bring Soul back to reality — to the ECK!"

With the last words, a single spotlight lit the middle of the stage, where another hooded figure stood in a white robe. I couldn't make out his features, but he began to speak in a narrative manner.

"The illusions man creates on the earth world have no value before Yama, the judge of the dead. There is no argument, there are no delays. Only justice."

The speaker's voice was brusque and formal. His short speech ended, he turned abruptly and walked to the rear of the stage. Just as he was about to exit, he stopped and turned. The spotlight followed his every move.

"But wait. Perhaps upon seeing the play we are about to show you, you will find the court of Yama to be all too familiar, all too commonplace. And perhaps, though accurate and honest, the play would fail to reveal the lesson it must reveal, due to the frequency of your own experiences with Yama. Therefore, may I propose to you a bit of deviance — a bit of novelty — and yes, a bit of unreality to reveal the real. Let there be humor in the form of satire. Begin!"

And with his final word, he snapped his fingers. The spotlight on the man in white disappeared; the stage went black, and a set of lights, just off center of the stage, popped on.

The brightly lit stage now revealed a judge's bench, with a grim, elderly, white haired man seated behind the high stand. He wore a black gown and reminded me of the courtroom judges in nineteenth-century English courts, as Charles Dickens might have described them. Unswerving justice, cold and unmerciful, was the only reason for their existence — to uphold the iron will and unseeing eyes of justice.

Two large, well-built men in modern police uniforms were dragging a wretched-looking man; each held him by the armpits as his feet dragged behind. They dropped him in a heap before the judge, and he groveled miserably on all fours.

One of the policemen stepped back from the groveling man and, with a tone of utter disdain, spat out at him, "Up knave! You are before Yama — judge of all karma of the lower worlds. Stand up and receive your sentence!"

The man on the floor, his head rolling about on his shoulders in woe-is-me fashion, slowly, stumbling, picked himself up off the ground.

With a frown that he looked like he was born with, Yama leaned over the bulky and imposing judge's bench to cast a disparaging glance upon his subject.

"So! Among the many transgressions of your miserable existence on earth, you are a thief! A weak, mewling, petty thief! What have you got to say for yourself, worm?" he bellowed.

The wretch, head hanging, clutched his hands to his chest, nervously rubbing them together. He looked here and there, but was afraid to look Yama straight in the eye.

"I…I…it's true I have been a thief…but I have confessed and asked for forgiveness…and now my sins have been washed away!" he said, not quite so sure of himself as his words would indicate.

Yama leaned forward, with both arms folded, and snarled in a low, ominous voice, "And just who has forgiven you?"

The wretch looked back and forth faster, as if at any moment a pack of wild beasts would come charging out of the shadows to tear him apart. He wrung his hands more and more nervously. "J-J-Jesus C-C-Christ-t-t-t. I have asked J-Jesus for forgiveness, and his dying on the cross has washed my sins away!"

Yama closed his eyes and shook his head in a slow, impatient manner. He murmured in a low tone, almost a whisper. "Imbecile. Weak excuse for a man!" Then his eyes opened wide at the wretch, and he clutched the edge of the bench, and tore into him like a serpent. "How dare you try to pin your transgressions on another! Why should Jesus Christ have to pay for your dirty little messes?"

Then Yama turned to the policemen. "Summon the shopkeeper this worm stole from, and get me Jesus Christ again!"

The policemen nodded and strode purposefully off the stage.

A moment later, they were escorting two men: one a smallish man with rolled-up shirtsleeves, balding, and in his mid-fifties, and the other a small man with short dark hair, in a white cotton robe, much like Sri Zadok's. One of the policemen announced, "Your honor, Jesus Christ and Benny Knatwing."

Yama nodded at the two men standing before him, then to the shopkeeper, Benny Knatwing, he said, "So what did he steal from you?"

Benny, with the indignation of the self-righteous, said, "Your honor, as you know, I run a pharmaceutical shop for the average man of the town…"

Yama interrupted, "You mean a bargain-basement drugstore, right?Listen Mack, forget the embellishments and stick to the facts. Short and sweet. Got it?"

Benny, as if he had a pole up his back, straightened, his demeanor humbled quite a bit. "Y-yes sir. Yessir your honor. A-as I was going to say, the thief stole a very large package of disposable razor blades. Fifteen for $1.59, marked down from $2.39."

Yama turned to the thief who was cowering off to the side. "Is this so?" he roared.

The thief, cringing and working his hands like he was washing them, stammered and mumbled something unintelligible to the floor. Yama leaned over to the thief and in a hiss, slow and deliberate, quiet like a cobra, said, "I can't hear you. Answer 'yes' or 'no'."

Miserable, the thief murmured a weak "yes."

Upon hearing the confession, Yama eased back, a sadistic smile of satisfaction upon his lips, and said, "You will reincarnate in three lifetimes to repay the debt to Benny Knatwing. Now both of you — go!"

Benny Knatwing looked pleased, and smugly started to walk off the stage. The thief scuttled up to him, like a beggar, and tugged at his sleeve.

"Listen, Mr. Knatlegs, I can't wait three lifetimes to pay you back — can't we work out something this next lifetime? I'll make it up to you three times over — honest!"

Knatwing recoiled from the thief and turned his shoulder to him, like he was a leper. "The name is Knatwing…and I don't know what I'm going to be in this next lifetime. And no, you can't pay me back now. You don't have anything to pay me with. You owe me $1.59, and $1.59 is what I'm going to get!" With that he walked off the stage.

Then the thief walked over to Jesus. "Jesus! Jesus! I went to church and prayed — sometimes, anyhow. I was a good Christian. I confessed my sins to you, and you died on the cross and forgave me. Now they say I have to reincarnate another three lifetimes just to repay the debt I owe Mr. Knatlips. Can't you do something about this?"

Jesus looked weary, but compassionate. "I'm afraid there's been some misunderstanding in what I said. I said that it was the Heavenly Father inside each of us that we must ask for forgiveness. God resides in our hearts, in each one of us. I can't repay a debt you incurred two thousand years after I left the earth and the physical plane. All I can do at this point is try to clear up any misunderstandings I've created. Do you want me to pay the $1.59 you owe?"

The thief stopped short for a moment and thought about this. Then, in a burst of emotion, he pleaded, "But what about your forgiving me? Doesn't that count for something?"

Jesus, showing patience, tried to explain again, "Like I said, the Heavenly Father within your heart is the only one that can forgive you for whatever transgressions you've incurred against the world. But the fact remains that you owe $1.59. All the forgiveness in the world will not erase that debt. It must be paid back in like coin. Not in forgiveness, not with pleadings — it must be repaid with $1.59. I don't happen to have any money. And even if I did and repaid the debt for you, there would be some point at which you would have to pay it yourself. I'm sorry. But there's nothing I can do."

As Jesus said this, he shrugged his shoulders, his palms upward in a gesture of helplessness. The thief cocked his head sideways and thought to himself for a second. Then, in a tone of disbelief, as reality hit home, he muttered to himself, "Well how d'ya like that? All those times I was praying for help and relief, and it turns out that I have to pay for all that stuff myself anyhow!" Completely ignoring Jesus and the others, he walked off stage without even a glance back.

Jesus shrugged his shoulders again and looked at Yama, who shrugged his shoulders; then Jesus made his way off stage. The lights went low again, until there was nothing left but the black, empty stage. The show was over.

Sri Zadok walked up behind me. "The man known as Jesus Christ was a contemporary of mine. We met on several occasions while he was preparing for his mission. We talked, but we both knew our missions were different. You see, because of the nature of Jesus's works and words, he must constantly return to the court of Yama until there are no more misunderstandings involving his name — which may very well continue until the end of the yuga, or until all remnants of karmic debt incurred in his name are cleared up. His mission was that of a world savior — and by this, he will be bound to the world."

I was a little puzzled by something though, and wanted to ask Sri Zadok, but was slightly afraid to; yet he picked up on my thoughts. "You have questions? Please ask. I will try to do them justice," he said with a smile.

The manner in which he said it was so unthreatening, that I felt it OK to ask. "Well, from what has been said, I'm not too sure what the ECK Masters mean when they say that their mission is to teach men to do all things in the name of the Mahanta. What's the difference in what Jesus said about the Heavenly Father within, and what the Masters say? Why wouldn't the ECK Masters be bound in the same way that Jesus is, if some chelas started doing outrageous things in the name of the Living ECK Master?"

Sri Zadok seemed ready for my questions and answered with extreme patience. "There are several differences. First, Jesus's teachings became the worship of the personality, for there was no other way to get his message to people in a manner that they would understand.This is the way of the saviors. He took on the karma of making his work known through the power of his personality. And so it is in this form that he must answer for the debts.

"When the ECK Masters lead the chela to the Mahanta, the Inner Master, there is no personality involved. The Outer Master is the teacher who clears up any misunderstandings he can on the outer, but when he leaves the earth, he leaves karma-free. There are no karmic debts attached to his personality, for he has guided the chelas to the Inner Master — the Mahanta.

"Now it is the nature of the Inner Master to teach self-reliance and self-responsibility. Since he is the highest representative of SUGMAD, yet resides in the heart of man, there is no outside agent to pin any blame or guilt on. The Mahanta reveals more of himself to the chela as the chela is able to demonstrate responsibility for his own actions.

"If a chela were to steal something, like the thief in the play, do you think he would ask the Living ECK Master to pay for it? I doubt the Living ECK Master would ever make any kind of payment for a transgression like that. It goes against the teachings of freedom and self-responsibility. Do you think the chela would then turn to the Mahanta to pay for it? Of course not! The Mahanta resides in the heart of the chela. It would be asking himself to pay for something he did. When you do something in the name of the Mahanta, you're acting as an agent of the Mahanta, the highest state of consciousness; it is a karmaless state. The Mahanta takes care of the chela's karma so it can be worked out more quickly. But this by no means is to say that the chela is home free. It means the Mahanta teaches the chela the laws of the lower worlds so he won't break any of them; thus he gains mastery of himself while residing in the lower worlds. Should you break a law, the Mahanta decides how much karma you will have to repay. He will speed things up, so the chela can learn faster than the cumbersome lords of karma would have him learn. He may work it so the chela can handle the payment without going off the deep end in debt, but in all cases the Mahanta will make it so the chela learns the lesson in the most expedient way.

"If the chela persists in breaking the laws or not listening to the Mahanta, there is not much that can be done. The chela must then face the full brunt of the penalties handed down by the lords of karma — slow and uncaring, devoid of love. After facing the lords of karma, the role of the Mahanta is appreciated in full.

"On the other hand, the followers of Jesus believed that he would take care of their karmic debts himself. Those following him dumped all their transgressions on him, doing nobody any good. They didn't learn the lessons of the laws of karma, and Jesus now has to answer for all the things done in his name.

"The only purpose of the Mahanta, the Living ECK Master is to guide the chela back home to SUGMAD. The rest is up to the chela. This is the difference between the world saviors and the Vairagi ECK Masters."

I thought of all saviors, savants and charismatic figures throughout history; it was all a show — like the phantom play Sri Zadok had me watch on the stage. I thought of the Mahanta, the Living ECK Master. There was nothing showy about him. Nothing pretentious, nothing unreal. He was the pure instrument of his mission: to show me and others who desired it, the way back to SUGMAD. This was the only show he was concerned with.

Wah Z stood there for a few moments more, until I understood that he was waiting for me to follow him. I got up from the comfortable chair as one does when he has just noticed that the last act of the play has concluded and realizes he is the last in the theater. Sri Zadok was gone — into the shadows and into infinity, and Wah Z and I were left to exit the theater together.

The dark lobby area didn't seem to be as dark as I'd remembered. In fact, it seemed familiar and friendly. Stepping through the opening in the plywood doorway, we came out onto the deserted street. There was no one else around — the last of the plays had let out long ago — so there were no happy and lively conversations drifting back down the street. Just the monochromatic grays and blacks of the night. But though the crowds had gone home and the night was silent, I felt laughter and light as we stepped into the lonely street, and I couldn't help feeling that this was a taste of what lay ahead in my life. There would be night times and dark, lonely streets — but there would always be the Mahanta beside me. And while he was with me, there would always be laughter and light.

As we walked in silence, I glanced at him from the corner of my eye, and knew that indeed, here, the real show was going on.

From the book, In the Company of ECK Masters © 1987 Phil Morimitsu