In this century, entire worlds of seemingly certain knowledge have crumbled. Time and matter were once the foundation, precisely measurable, weighable, computable, the most certain things . Our understanding of the world was founded on them, all processes of perception were based on them. Today, theoretical physics is confronted with the ruins of what once were time and matter.

Ever since Einstein — since his special theory of relativity (1916) — we are aware of the illusory, "crutchlike" character of time. Now we know there are events that seem to be taking place simultaneously from one vantage point, while from other viewpoints they appear as successive phenomena, progressing from the past over the present and into the future. The concept of time in modern physics is remarkably similar to the "eternal presence" that flows into many different directions, a concept inherent to the philosophy of Hinduism for thousands of years.

Let us imagine we are observing a distant spiral nebula out in the depths of space (a routine observation in modern astronomy)–say, somewhere in the region of Cassiopeia, five hundred million light-years away. What happens when we think we see Cassiopeia? What do we see? Obviously something that was there 500 million years ago. Maybe Cassiopeia doesn't even exist any more. But quite obviously we are looking at it "now," Without a doubt, we are looking backwards, from the present into the past; and both are "now."

The farthest known systems in outer space are five billion light-years away. When we observe them we are observing something "now" that existed before the earth was even formed.

This train of thought shows that space can turn into time and time can turn into space. A light-year is the distance that light travels in one year. In one second, light travels 186,000 miles; in one minute, it travels 186,000 x 60 miles. In one hour, this sum is multiplied by 60; in one day, that sum is multiplied by 24; in one year, this sum again is multiplied by 365 — all in all, the unimaginable distance of six trillion miles. Thus the light-year is a working metaphor for a distance whose spacial extension, even more than its temporal aspect, is beyond all "normal" imagination. We will find that in terms in physics are "metaphors," including those that play a central role in the present chapter: time and matter.

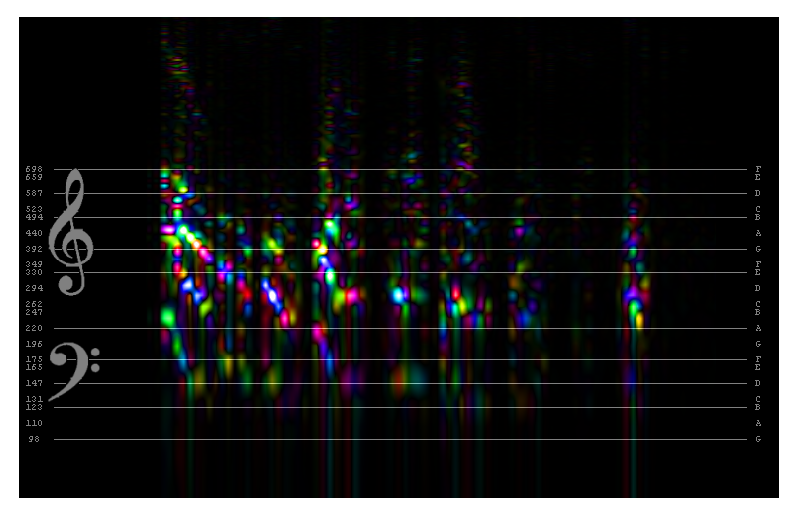

Obviously, space and time are related to each other also in the smaller dimensions of our earth. We simply fail to notice it. Here's a simple example: The longer the string (the larger the spacial aspect), the lower the resulting tone when the string is plucked, that is, the slower the vibrations of the string (which means: the larger the temporal aspect). The resulting rule was formulated by Hans Kayser: "As the spatial aspect, the string length diminishes, the temporal aspect, the number of vibrations, increases, and vice versa."

The modes of time (past, present, and future) can seamlessly turn into spacial concepts. Under certain circumstances temporal concepts can define things normally expressed as spatial concepts — distance, extension, or length.

For all practical purposes, there is no difference between space and time in certain computations in theoretical physics. The words space and time have lost their separate meanings. It is of no relevance to their mathematics whether the two concepts are used interchangeably, treated as equal or as a unit, or are kept strictly separate in the conventional way.

The great nineteenth-century mathematician Bernhard Riemann already tended to mathematically change time into space. In the course of the years, it became more and more untenable that the one dimension of time and the three dimensions of space perceived by our senses should be sufficient as the base of a realistic picture of the world. As it became increasingly reasonable to assume that our world has at least four, if not many more dimensions, the most diverse theories were proposed, based, for instance, on two temporal and three spacial dimensions (by the British physicists Arthur Eddington and Adrian Dobbs), or on the assumption that time is nothing but a misinterpreted spatial dimension. In mathematical terms, worlds with five, six, or more dimensions function flawlessly; in fact, some physicists have pointed out that their mathematics work better than those of the system of three dimensions that our optical and tactile senses perceive. In this regard, P.D. Ouspensky reminded us in Tertium Organum that it is impossible to find a mathematical foundation for our system of three dimensionality:

How shall we understand that mathematics does not feel dimensions — that it is impossible to express mathematically the difference between dimensions? It is possible to understand and explain it by one thing only — namely, that this difference does not exist…[In this way we see] that no realities whatever respond to our concepts of dimensions…The representation of dimensions by powers is perfectly arbitrary.

When trying to make the "illusory" nature of our concept of space and time understandable, it has become customary to postulate the existence of two-dimensional beings as a sort of "mental bridge." While we cannot imagine a world with more than three dimensions, we can approach it to a certain degree by picturing the world with less than three dimensions. Imagine, then, a creature that lives on one plane only, say, on a table top. It knows only two dimensions, height and width. For such a creature, as Ouspensky points out, "a circle or square, rotating around its center, on account of its double motion will be an inexplicable and incommensurable phenomenon, like the phenomenon of life for a modern physicist." When a multicolored cube is passed through the surface on which the two-dimensional creature lives,

…the plane being will perceive the entire cube and its motion as a change in color of lines lying in the plane. Thus, if a blue line replaces a red one, then the plane being will regard the red line as a past event. He will not be in a position to realize the idea that the red line is still existing somewhere….For the being living on the plane, everything above and below…will be existing in time, in the past and in the future…Therefore, though not conceiving the form of his universe, and regarding it as infinite in all directions, the plane being will nevertheless involuntarily think of the past as situated somewhere at one side of all, and of the future as somewhere at the other side of this totality. In such manner will the plane being conceive of the idea of time. We see that this idea arises because the two-dimensional being senses only two out of the three dimensions of space; the third dimension he senses only after its effects become manifest upon the plane, and therefore he regards it as something different from the first two dimensions of space, calling it time.

We know that the phenomenon of motion or the manifestations of energy are involved with the expenditure of time, and we see how, with the gradual transcendence of the lower space by the higher, motion disappears, being converted into the properties of immobile solids; and biological phenomena — birth, growth, reproduction, death — would be regarded as phenomena of motion.

Thus we see how the idea of time recedes with the expansion of consciousness.

We see its complete conditionality.

We see that by time are designated the characteristics of a space relatively higher than a given space — i.e.., the characteristics of the perceptions of a consciousness relatively higher than a given consciousness….

In other words, the growth of the space-sense is proceeding at the expense of the time-sense. Or one may say that the time-sense is an imperfect space sense (i.e.., an imperfect power of representation which, being perfected, translates itself into space-sense, i.e., into the power of representation in forms).

If, taking as a foundation the principles elucidated here, we attempt to represent to ourselves the universe very abstractedly, it is clear that this will be quite other than the universe which we are accustomed to imagine to ourselves. Everything will exist in it always.

This will be the universe of the Eternal Now of Hindu philosophy — a universe in which will be neither before nor after.

"To put it differently," writes Lama Govinda, "we do not live in time, but time still lives within us….Space is eternalized, objectivated time, time projected outward. Time…is internalized, subjectivated space….Time and space are related to each other as the inside and outside of the same thing."

A similar view is held by German philosopher Jean Gebser: "The body…is nothing but solidified, coagulated, thickened, materialized time." Gebser postulates the "integral man" who has become "free of time."

When interpreting certain scattering processes in quantum mechanics, it can happen that a particle will be moving forward in time in one process, while in the immediately adjacent process it will be moving backwards in time. In fact, time may progress forward for a particle interpreted as a positron, and backwards for the same particle interpreted as an electron. Both interpretations are physically conclusive and both are mathematically "correct."

Only ten years ago, physicists thought that such phenomena were limited to the field of quantum physics, with its unimaginable small dimensions. In the meantime, however, they have computed that certain situations are thinkable ( must be thinkable from a logical point of view) wherein processes of the microworld also appear in macrophysics. In fact, Ilya Prigogene, a Soviet-born physicist living in Belgium, was awarded the 1977 Nobel Prize not least for this very discovery.

Werner Heisenberg has shown that field equations for electromagnetic fields can be solved mathematically not only for events in the past but also for future events. In many respects, all these words — past, present, future, cause, and effect — have taken on a ring of absurdity, much like closed control loops of cybernetics in our excursion into logic.

The interpretation of time as a spatial dimension that our senses are unable to perceive opens possibilities for explaining countless psychic phenomena so well-documented that even skeptical scientists do not doubt them (such as precognition, prophecy, clairvoyance, and deja vu). One example is the frequently observed fact that in the event of a forest fire or an earthquake, animals leave the danger zone before the actual disaster takes place — a particularly impressive sight at the eruption of Mount Saint Helens in the state of Washington in 1980, or during a wave of forest fires in northern Germany in 1973. Very few animals lost their lives in these disasters; most of them had fled as if they had sensed what was about to happen. Only the human beings stayed at the scene. Quite obviously, animals (and surely also, as Jean Gebser supposes, "archaic" man of prehistoric times) have a gift that among us rational and "mental" human beings is limited to a few especially blessed (or cursed?) individuals — the gift of being able to perceive time as a spatial dimension, simply as a distance stretching before us that we can "see." This is the sense in which time and again great clairvoyants of all ages have described their special gift as seeing into a distance opening up in front of them — as distance and as space. As I have mentioned, the mathematical realization of this concept offers no problems; it is "correct."

I have structured the present chapter in such a way that the concepts of time and matter of both modern physics and the thinking of Asia merge together, patchwork fashion, into one. Lama Govinda writes:

When speaking of the perception of space in meditation, we are dealing with a wholly different dimension…where temporal succession becomes simultaneity, where spatial parallelity becomes a fusion of one into the other, where fusion becomes a living continuum beyond existence and nonexistence in the merger of space and time.

As much as seven hundred years before theoretical physics, the famous Japanese Zen master Dogen realized: "Most people believe that time passes. In reality, it stays where it is. The concept of the passing of time is false, because man, limited to experiencing time only as passing, does not understand that it stays where it is." And D.T. Suzuki, the contemporary communicator of Buddhism, comments:

"In the spiritual world, there is no such thing as past, present, and future." Einstein meant precisely the same thing when he stated: "For a believing physicist like myself, the seperation of past, present, and future has the value of a mere, albeit stubborn illusion."

It is clear that there is no contradiction between the interpretations of time by modern physics, on the one hand, and by Buddhism and mysticism, on the other. In fact, the further physics progresses the more similar these two conceptions become. We shall return to this point later on.

Most of us would agree that when time becomes endless, it becomes eternity. In the thinking of most people, time as succession of past, present, and future is nothing but a section of eternity. Yet does not such an interpretation represent the —unconscious— attempt to dispel eternity as much as possible from our human life and consciousness, into an endlessly distant past on the one hand and into a just-as-endlessly distant future on the other? The point here is not to reflect upon the psychological implications of such an attempt — as interesting as that might be — but to remind ourselves that over the centuries the spiritual wisdom of both East and West has known eternity is now: in this moment. Suzuki: "Eternity is the absolute present."Saichi, one of the masters of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism, said: "Being reborn means this present moment."

The same knowledge had also existed in European mysticism, because Buddhism and Christian mysticism actually speak "merely two dialects of the same language," as Erich Fromm put it. A key word in the thinking of the great thirteenth-century German mystic Meister Eckehart was "Now." This "Now" means both the present moment and eternity, because "the now-moment in which God made the first human being, and the now-moment in which the last human being will disappear, and the now-moment in which I am speaking are all one in God, in whom there is only one now." The power of the Soul "knows no yesterday or day before, no morrow or day after (for in eternity there is no yesterday or morrow): therein it is the present now; the happenings of a thousand years ago, a thousand years to come, are there in the present and the antipodes the same as here."

The same is meant by modern "mystic," the twentieth-century writer Franz Kafka: "Only our concept of time makes us call the Last Judgment by that name, actually it is martial law."

Characteristic of martial law is that the deed, the apprehension, the judgment, and its execution fall together so narrowly that the time between them no longer exists.

Projecting the "Last Judgment" into the future (especially into an unimaginably distant future) is literally what the word means, a projection in the sense of psychoanalysis. The fault always lies with the other person. He is responsible. In this case, we enshroud the future with a fog as densely as possible. Nothing is "foggier" than eternity, which is so far removed from us that we can rest assured that nothing can happen to us.

An ancient Zen mondo tells of the knowledge that eternity is "now"; this mondo has been handed down to us in the most diverse forms and is attributed to various Zen masters, which indicates that it has become common wisdom:

It is springtime. The Zen master and his pupil work in the garden. There, a flock of birds in the sky! The pupil says to the master: "Now it will turn warm, the birds are coming back." The master answers: "The birds have been here from the beginning."

You can feel that Buddhism — Zen in particular — and European mysticism essentially are of one mind. As Professor Gorbach of the University of Copenhagen writes:

Basically, mystics throughout time have expressed the same thing; in fact, they are in such agreement they often use the same words and images. Certain scriptural passages from ancient India, thousands of years before our civilization began, are almost identical with those written by European monks during the late Middle Ages; and even creations of modern poets are reminiscent of ancient scriptures. The reason for this agreement is that they all share a common experience that is as clear and convincing as what the average person perceives in his material world. There is no room for dreams and fantasy here. The mystic is dealing with an experience that shapes his whole life.

All these quotations — do they not express a certain glimpse of freedom? We are all slaves of time, of its inescapable motion. "The birds have been here from the beginning." The man who said that is free of the tyranny of time.

At this juncture, a phenomenon from the days of the French Revolution may be highly illuminating. According to several unanimous eyewitness reports, on the evening of the first day of fighting in July 1789, revolutionaries in various sections of Paris destroyed the church clocks, independently of one another and without prior agreement. Spontaneously they became aware of the clocks as symbols for the tyranny to which they had been subjected. In this truly "clairvoyant" moment, time and tyranny had become synonymous for them. Now, everyone had his own time. Just as Salvadore Dali's paintings, there is no need for clock hands. The time is now. "The birds have been here from the beginning."

Freedom from time, as Jean Gebser once put it, is freedom per se. Clocks have to do with lack of freedom. Just consider how quickly medieval Europe covered itself with a network of clocks as soon as that became technologically feasible. This was done so eagerly and unnoticeably that the chroniclers could hardly keep up with the process. Thus we do not even know exactly who invented the first mechanical clock for a church tower. Perhaps it was Pacificus, the archdeacon of Verona (d. 846); perhaps it was Gerbert of Aurilac (c. 950 – 1003), who constructed the famous clock in Magdeburg in 966 and who later became famous himself as Pope SylvesterII; perhaps it was the abbot Wilhelm of Hirschau (d. 1091). This knowledge has been lost in the fog of history. The only thing that we know for sure is the fact that it was the clergy who saw to it that the mechanical clock became a functioning timepiece.

After Paris got its first public clock around the year 1300 and Milan got one in 1306, followed by Caen, Padua, Nuremberg, Strasbourg and other cities, the fourteenth century became the " century of the mechanical clock." Before the close of the fifteenth century, it was almost a matter of course all over Europe that even the smallest church had a clock in its steeple, even when several other churches were built close by. Each of these clocks had its own hourly toll, insisting on time every sixty minutes. Soon there were clocks striking every thirty and every fifteen minutes, so that even those who could not see the face of the clocks were constantly reminded of the admonishing finger of time and its tyranny. Hardly a stroke of the bell sounded but that it was answered (a few seconds or minutes earlier or later) by some other church within hearing range, intensifying the general insistence on time. The chiming of the clocks in the cities was carried into the suburbs from there across the land into the villages, and from one village to the other. From Sicily to Scandinavia and from Great Britain to Poland and Russia, Europe had donned a gigantic hood of church clocks and bells. In the improbable case that some sleeping citizen was not aware of the time, night watchmen in the cities wandered through the streets reminding everyone with their dreary singsong: "Ten o'clock and all's well." No other culture has anything comparable. The call of the muezzin a few times a day from the mosques in the Islamic world is nothing in comparison with the constant reminder in the cities and villages in Europe. And here we should bear in mind that it was the monks and priests, the institutions of Christianity, who cast the net of time along with their teachings over the continent, as if the clocks could help them (which they did) to keep countrymen, citizenry, and nobility under close scrutiny, in a never-ending, flagrant insult of their Lord and God whom they profess to be "free of time" : "A thousand years in they sight are but as yesterday when it is past, and as a watch in the night" (Psalm 90:4)

Most philosophers of time differentiate between "lived" time and "measured" time, between "subjective" and "objective" time. Measured time is considered to be steadfast and precise, the same time and obligatory for all people. Lived time is the professional time of each single individual, passing by much too fast during moments of bliss and much too slowly in the hour of suffering. According to what we know today, however, anyone who takes the theory of relativity and the principle of uncertainty to their logical conclusions must judge the value of these two kinds of time almost in total contradiction to what was upheld two or three generations ago: Lived time, which only recently was called "relative," now seems to be much more dependable than the kind of time that just as recently was considered to be "objective" and that has been relativized so much that little of it is left to be "objectivized." At least we can feel our personal, "lived" time, whereas the physicists have to admit that "objective" time cannot even be measured dependably and that nothing certain should be said about it.

Even the ancient Greeks have been "unconsciously conscious" of the difference between measured and lived time. They had two gods of time: Chronos and Kairos. Chronos, the archfather, was the god of absolute, "eternal" time. For Kairos, however, the youngest son of Zeus, time simply meant the favorable moment, the "right time." Penelope Shuttle and Peter Redgrove have shown that Kairos has a more female approach to time while Chronos has more male elements.They found the male element to be rigid, proud of its "objective" measurement of time, and the female element to be relative, "waxing or waning," just as women are subject to natural cycles: "In the female consciousness, time is subject to the Kairos and less to the Chronos of the male consciousness, although both can be experienced by the same person."

The "most lived" of all times is the female cycle. The woman lives it each month. More than anything else, this cycle is her "inner" clock. In fact, certain scholars are of the opinion that primeval man first experienced time through the female cycle. That was the actual primal meter — and there we have it: the Greek word metra originally meant "uterus." It was the measure, there was no other one. Metre, the Ionic original form, has no plural, that is, no different measures. Mater ("mother") is related to the word. Almost all words expressing "measure" (including this word itself) come from this root: mensuration, immense, dimension, meter, diameter, parameter, thermometer, meteor, and so forth, across all languages, even in Sanskrit. There, matri is the mother and matra is the measure. Even though it is almost unimaginable for modern rationalistic man, let us try to become aware that the term "germ cell" for all these different words is in metra, the uterus. It brought forth — measure! It was — measure. By coming forth from the uterus, man emerges from measure to become mater-ial!

Rationalistic Western civilization has suppressed its Kairos. Its time is taken with clocks and watches, with (take note of the word) chronometers. Its time comes from archfather Chronos, the patriarch. It is male, patriarchal, rational, and functional. In the more archaic cultures, however, as in those of the African continent, even today the time of Kairos is more important than clock time, which is "primal time" only for male-dominated thinking.

Meanwhile, we have discovered the ironic (and even somewhat "Ionic") fact that modern particle physics, although unthinkable without measurements and clocks (i.e., without Chronos), is no longer quite as far from Kairos as it previously appeared to be. As we said, for Kairos time is the right moment, the favorable hour, the good opportunity, sensitivity to the right measure and the fitting relationship. And that is just what time is for quantum theory and Heisenberg's principle of uncertainty. For photons and electrons and for quarks and leptons, time exists only as a "good opportunity" or as "right moment," but certainly not as clocked time and even less as the supposed "primal time" of Chronos

.

To make Kairos the son of Zeus, indeed his youngest son, and to attribute measured time to the archfather Chronos — from a logical point of view as well as in terms of physics and the history of evolution, this must be counterfeit, a reversal of the way things really proceeded. For doesn't the actual sensation of time begin by someone perceiving the right moment? First came the measure set by the uterus, the female time; first came lived time, the right moment. Only then came the measured time of Chronos, the patriarch, who according to the ancient Greeks mated expressly with Ananke, the goddess of coercion in the sense of "necessity" but also that of violence and suppression. One can well imagine that he must have loved her! (Haven't we seen that time loves tyranny?) The fact that the descendants of Chronos "murdered" Kairos so effectively that today he is virtually unknown by anyone but classical philologists is a truly "oepidal" crime whose analysis is long overdue. The whole scheme, as I have said, is counterfeit, and it is obvious at what point in time it must have been made: during the era of transition from the original matriarchal society to patriarchal society. There is an aspect of Ionic-Greek humor in this forgery, as if someone were sitting behind it trying to hide his roguish Odyssean grin — just like Ulysses and his men in one of their bits of knavery (and indeed it is a forgery that could have been devised only by males). I could propose a headline for the story: "The Greek's Prank With Time."

Now to matter. Under the influence of modern physics, matter has become almost more radically frayed than time. And yet it used to be so for Western society: There is nothing more certain than this chair on which I sit, and this desk at which I work, this typewriter on which I hammer all night long….Now, however, the nuclear physicists verify what Buddha and the sages of Asia have said all along: Matter is emptiness. Material is "not."

Let us begin this section on matter with a quote from The Silent Pulse by George Leonard, a book that I recommend highly to anyone wanting to know more about the present context:

The electron microscope allows us these perceptions of the body , a beautiful and terrible place, seemingly as spacious as the sea….As the magnification increases, the flesh does begin to dissolve. Muscle fiber now takes on a fully crystalline aspect. We can see that it is made of long, spiral molecules in orderly array. And all these molecules are swaying like wheat in the wind, connected with one another and held in place by invisible waves that pulse many trillions of times per second.

What are these molecules made of? As we move closer, we see atoms, tiny shadowy balls dancing around their fixed locations in the molecules, sometimes changing position with their partners in perfect rhythm. And now we focus on one of the atoms; its interior is lightly veiled by a cloud of electrons. We come closer, increasing the magnification. The shell dissolves and we go on inside to find…nothing.

Somewhere in that emptiness, we know, is a nucleus. We scan the space, and there it is, a tiny dot. At last, we have discovered something hard and solid, a reference point. But no — as we move closer to the nucleus, it too begins to dissolve. It too is nothing more than an oscillating field, waves of rhythm. Inside the nucleus are other organized fields: protons, neutrons, even smaller "particles." Each of these, upon our approach, also dissolves into pure rhythm.

Scientists continue to seek the basic building blocks of the physical world. These days, they are looking for quarks, strange subatomic entities, having qualities which they describe with such words as upness, downness, charm, strangeness, truth, beauty, color, and flavor. But no matter. If we could get close enough to these wondrous quarks, they too would melt away. They too would have given up all pretense of solidity. Even their speed and position would be unclear, leaving them only relationship and pattern of vibration.

Of what is the body made? It is made of emptyness and rhythm. At the ultimate heart of the body, at the heart of the world, there is no solidity. Once again, there is only the dance.

Lao-tzu once said: What makes a wheel a wheel is the emptyness between the spokes. In this sense, what makes an atom an atom, is the emptiness between the elementary particles. An atom, enlarged to the size of the Empire State Building, would have a nucleus about as big as a grain of salt. This, then, is how we have to imagine matter — so empty: a grain of salt whirling through the Empire State Building at a speed of approximately thirty-six thousand miles per hour. Or the other way around: A human being, compressed into those parts which can truly be called "matter," would be invisible to the naked eye; he would be the size of an atom. One more metaphor as an aid to the imagination — this one borrowed from Isaac Asimov: If one wanted to fill out the entire volume of one atom with nuclei, one would have a thousand trillion atomic nuclei.

Upon closer inspection, however, the "nucleus" itself dissolves into smaller and smaller particles, into more and more "empty" dimensions! For half a century, this has been going on: Whenever a "final," smallest, "indivisible" nuclear particle is discovered, it doesn't take more than a couple of years before an even smaller one is found.

In the beginning was the atom (from the Greek átomos, which means "the indivisible" but also, interestingly enough, "that which is sacred to the gods," in this latter sense originally understood not materially but harmonically as the smallest musically meaningful interval, 45:46). Then came electrons, neutrons, and protons (from the Greek word for "the first," because this too was believed to be the "first" and smallest of all particles), and then a breathtaking series of smaller and smaller particles all the way to the photons and quarks, hadrons and leptons, gluons, tions and myons, and more recently on to the weakons, the Z zeros, the rishons, the tohus and vohus. The last three particles were discovered by physicists in Israel in 1980. Two are named for the biblical phrase "tohu va-vohu" (Genesis 1:2), meaning "without form and void," that is, the state of the world before God put it into order. In Hebrew, rishon is what proton is in Greek: the most original, very first entity.

In the meantime, more than two hundred such entities have been discovered. Many physicists are aware of the fact that the word "elementary particle" can only be used in an ironic sense. Indeed, nothing is less "elementary" than what we are accustomed to call "elementary particles." Many of these are not very "elementary" particles exist for minute fractions of a second before they disintegrate into even smaller particles or into waves or energy. As we mentioned, they move from past to future as well as backward, from the future to the past. What used to belong to the realm of folktales and myths really exists after all: a life moving backward, from that which is to come to that which has already been. What has been "tomorrow," will be "yesterday."

Since each of these particles has its antiparticle, we also know that there is "antimatter" and, thus, an "anti world," In it, each particle has the opposite charge of its counterpart in our "real" (impossible, not to put this word in quotation marks) world. Scientists have already succeeded in producing antimatter, even though only for fractions of a second and in smallest amounts. Physicists are now asking the question: "Where is the antimatter that must have come into existence together with matter at the beginning of the universe? Maybe there are entire galaxies consisting of nothing else but antimatter" (Isaac Asimov).

Fritjof Capra, author of The Tao of Physics, has made the following remarks: "The creation and destruction of material particles is one of the most impressive consequences of the equivalence of mass and energy….The classical contrast between the solid particles and the space surrounding them is completely overcome….Particles are merely local condensations of the field; concentrations of energy dissolving into the underlying field."

As early as the second decade of the twentieth century, one of the founders of modern nuclear physics, Niels Bohr, was among the first to understand the implications of the disintegration of matter "into nothing": "For a parallel to the lesson of atomic theory….[we must turn] to those kinds of epistemological problems with which already thinkers like the Buddha and Lao-Tzu have been confronted."

Let us remember that the concept of zero was first developed by Hindu mathematicians, as early as the sixth century. From the mathematics of India, the zero was adopted in Arabia; and there European mathematicians "discovered" it and adopted it. Without zero, all Western mathematics (the foundation of modern physics) would have been impossible. The preoccupation of Hindu philosophy with the "void," with "nothing," was the original impetus, for the Hindu scientists derived their mathematical concept of zero from the philosophical and spiritual understanding of "nothing." This is the source of the rule in differential calculus that the result of zero divided by zero can be any number — zero, one, or infinity. Because the "nothing" created everything. Just as it does in modern physics.

As early as the fourteenth century, Zen seers developed the formula "Shikisokuseku": "Matter is void" and "Void is matter."

Capra has pointed out that the two foundation stones of twentieth century physics, quantum theory and the theory of relativity, force us to look at the world much as a Hindu, a Buddhist, or a Taoist would see it. Capra quotes a famous sutra attributed to Buddha himself: "Form is emptiness, and emptiness is indeed form. Emptiness is not different from form; form is not different from emptiness. What is form that is emptiness; what is emptiness that is form."

There has been tension — even hostility — between the natural sciences and the institutions of the Christian church for centuries. Galileo, Bruno, Kepler, and other great scientists were persecuted, incarcerated, burned at the stake; Darwin and Einstein were discriminated and fought against. Between the natural sciences and the concept of the world in Asia, however, there is basic concurrence. Thousands of years before Einstein formulated his theories concerning time and before the discoveries of quantum physics about matter, the Buddha said the same things, only in different words. In fact, even before the Buddha, the philosophy of Hinduism referred to space as akasha (from the Sanskrit root kash, "to shine, to appear"). And every student of Hindu and Buddhist thought is familiar with the term shunyata —the void, a void that is fuller than wealth, which again leads us to the dictum: "Void is plentitude" and "Plentitude is void."

On trips to Asia, many modern physicists have experienced the parallels between their own findings and those of Asian spirituality. When Neils Bohr was in China in 1937, he was impressed by the notion of complementariness as an essential part of the Chinese worldview. And when he returned home to Copenhagen, he added the Chinese yin-yang symbol ti his family coat of arms.

Capra has shown that the findings of the theory of relativity and those of quantum mechanics sound as if they were Zen koans, the seemingly absurd meditation tasks given by Zen masters to their pupils. He feels that quantum theory may be the ultimate koan of our times.

The British physicist James Hopwood Jeans has concluded:

There is broad agreement today, bordering on unanimity in the avenue of physics, that the stream of knowledge is flowing toward a non-mechanistic reality; the universe is beginning to look more like a mighty idea than like a machine. The spirit no longer seems to be a casual trespasser in the territory of matter. We are starting to presume that we should rather welcome it as a creator and rector in the field of matter.

In 1964, the Swiss physicist J.S. Bell pointed out that "no theory of reality compatible with the quantum theory can proceed from the assumption that spatially separate events are independent of each other." Anyone raised in the spiritual tradition of Asia will stop short in amazement here, because this tenet — which has acquired worldwide acceptance in theoretical physics as "Bell's theorem" — means exactly the same as that which the sages of Asia have always known: Nothing in the cosmos, how ever wide its boundaries may be, is separate from anything else. "Everything is one." "Tat twam asi."

Let me present another quote from the works of George Leonard:

For quantum theory to really work, to put it into everyday language, each electron has to "know" what all the other electrons in the universe are doing in order to "know: what it's to do. It's as if at every point in every electromagnetic field there were a tiny supercomputer that was constantly figuring out everything that's going on in the universe….In such a universe, information about the whole of it is available at its every point.

These implications of quantum theory resonate with the deepest intuition of the ages, the direct experience of the most revered spiritual masters, and the thought of such philosophers as Leibniz and Spinoza and Whitehead.

Ilya Prigogine has remarked that Darwin's theory of evolution was an early step in this direction, implying as it does that all forms of life are connected with each other. "The expanding universe implies that all things in the cosmos are interconnected." Exactly the same thing was said by the Chinese Zen master Ch'an-sha Ching-ts'en in the ninth century: "The whole universe is in your eye. The whole universe is your source of light. The whole universes within your own source of light. In the whole universe, there is nobody who is not your own self."

Here one is reminded of the famous pearl of Lord Indra, which reflects all other pearls in the world and which at the same time is contained in every other pearl in the world. For the ancient Brahmans, it was a symbol of the universe. Wise men in India use it as a meditation task: Penetrate the absurdity of Indra's pearl; it reflects all the pearls in the world and yet lies within every other pearl. Grasp this!

To the rationalist, the pearl may be a metaphor (physicists also have only metaphors!), but the metaphor corresponds precisely with the theories of quantum mechanics and the more recent findings of particle physics, which has developed theorems like the following: "Each particle consists of particles." Or: "Each particle helps produce other particles, which in turn produce the particle itself." These read as though they were Buddhist sutras, but in fact they are theorems of modern particle theoretical physics.

The actual point of Heisenberg's principal of uncertainty is something the Buddha and Zen masters have always been certain about, the fact that only our perception of things makes them what they are. A particle is a wave if I want to look at it as a wave. It is matter if I want to look at it as matter. The particle may be on the moon, but when I consider it as a wave, it is a wave. If someone else up on the moon were (simultaneously) to consider it as matter, it would be matter. If I look at it as a positron, it is a positron. If I look at it as an electron, it is an electron (and the direction of time is reversed). My observation is thus able to reverse time, past into future and vice versa, positive into negative and vice versa. That is the actual point of the principle of uncertainty. Whatever we may say about the world, we ourselves are in the middle of it. We cannot leave it. We are "in" things, in the smallest particles, in the "core of the pearl."

Heisenberg's principle of uncertainty is more than half a century old and yet is still acknowledged only by physicists. The rest of us look upon it as something exotic, like a message from a distant star, although it should long ago have revolutionized our entire attitude toward the world. Only then could our thinking really be called "modern." As long as we do not understand the message of the new physics, our way of thinking is antiquated, premodern, a school of thought from the nineteenth century. One example is traditional medicine. Without consideration of the principle of uncertainty, it becomes a "medicine of uncertainty" — which, in fact, it is.

With his principle, Heisenberg discovered a fundamental concept that is valid not only in microphysics. Let me repeat: Observe a particle as a wave, and it is a wave. Observe it as matter, and it is matter. So the principle of uncertainty is a principle of the point of view. If we were not so deceptively sure of the "objectivity" of our point of view, we humans would have noticed a long time ago that we have been living with the principle of uncertainty from the beginning of our evolution. Almost all of us have had the following experience: You see things from your point of view, and no doubt, you consider your point of view correct. Someone else, however — your father or your friend or your lover — looks at the problem from a different angle and comes to the opposite conclusion, which for that person is just as undoubtedly correct as yours is to you.

Thus it is our point of view, the way we look at reality, that makes reality the way it is. In the nineteenth century, most people in the Western world were aware of the idea of "the survival of the fittest." The nations of the small continent of Europe had subjugated the greater part of the world and were ruthlessly exploiting it. Year after year, the process of exploitation was making headway. Nations were exploiting nations, capitalists were exploiting workers, workers were exploiting their wives, families were exploiting their children. Education was directed from the first — not just by the schools — at establishing those patriarchal and authoritarian structures in society that helped legitimate the general process of exploitation. Industrialism and capitalism led to fantastic profit margins. It all worked marvelously, and it was obviously all based on exploitation. Exploitation was inevitable. Everyone is everyone else's enemy. Everybody fights against everybody else. The more ruthless the struggle is, the more rapid the progress. Darwin's theory of the survival of the fittest and the interpretation of the evolutionary theory that most of us were taught in school fit perfectly into this picture. There was a need for this kind of theoretical foundation so science furnished it.

In the meantime it had become clear that the concept of evolution by struggle, destruction, exploitation, and the survival of the fittest is a matter of point of view. That idea stood in precise correspondence to the way the people in Europe (especially in Britain) thought and behaved at that time. Today many scientists realize that what the old biology explained as parasitic exploitation was in fact symbiotic cooperation. We have to understand that parasitic types of relationships are not characteristic of nature. The opposite is true: symbiotic aid is part of the idea of evolution. We know that the majority of all living creatures have "understood," each in its own way, that all living things are connected with each other and that the death of a partner (even of an enemy) or the extinction of a race (again, even of an enemy) also means danger for all other partners or races, danger for the entire system of life. We have learned that those predatory relationships that our grandfathers (and even our fathers) tried to teach us as "typical in nature" are exceptions; that, in comparison to the billions of cooperative and symbiotic relationships in nature, there are not very many "murderous" ones; and that we have noticed the "murderous" ones precisely because they are so rare. Now we realize that human beings distorted the partner roles that are naturally dominant in creation, turned them into those of a predatory relationship as justification for their own behavior. They projected themselves onto nature — and those who overly "project" need therapy.

Nineteenth-century science "celebrated" the "survival of the fittest," because down deep it wanted to celebrate the "fittest" — the human being. The new biology, by contrast, "celebrates" the bonds between all living creatures, because now more important than the "celebration" of the human being is the survival of life (including human life) on this planet.

I have cited this example in such detail not only because it illustrates the new consciousness with which this book deals, but also because it shows so clearly that the phenomena prevalent in particle physics are not limited to the microcosm. Not only in physics, but also in other sciences (in biology, for instance) is "certainty" relative to the point of view or the level of consciousness.

If we could only acknowledge that this holds true even for the areas of religion and spirituality, we would become more tolerant. Westerners pray to one God as the Christian God, to Jesus Christ, the Lord Almighty. Arabs pray to one God as Allah of Islam, the Lord Almighty. Indians pray to Brahma as Lord Brahma, the Creator and Lord Almighty. Whatever the religion, it is always the almighty God ( or an almighty principle, or the almighty nothingness ). There is no way of deciding who is right. All are right. In every culture there are people who have experienced beyond a doubt that they are right.

Is this a relativistic point of view? Is it even a denial of the divine principle?Is it not rather the opposite? The absolute certainty that the believers are right in not only one of those religions and cultures but in all of them? We do not deny a particle if we look at it as a wave here and matter as there. The particle exists. And yet it is dependent on us. God exists in the same sense. But He also is dependent on us. The great mystics of all cultures have known it as long as mankind can remember: He is within us.

The discovery of the laser beam led to the development of holography, a kind of photography with laser waves. Surprisingly, a "picture" produced by holography cannot be divided. If it is divided, it "jumps" back to form the full picture. Divisions or detail sections cannot be produced. Even a smaller format shows the holos, the whole (from the Greek word ˀólos, "whole"), although somewhat less brilliant. Theoretically, one could go on dividing down to microscopic dimensions; a detail section would never be produced. The picture remains itself, even if the picture itself should become an elementary particle. Which means that in each elementary particle there is the whole, the entire universe. Physicists working with holography could easily subscribe to the Buddha's realization that "everything is one."

From this angle, too, we have reached a point that became visible in the first part of the chapter when we talked about time. Physicists today are asking whether the so-called psi-phenomenon of parapsychology might not be seen as "natural" from the vantage point of quantum mechanics — phenomena such as precognition, materialization, dematerialization, and telekinesis. If everything is one, even the most distant things must be here and now.

In an article on physics and parapsychology, Wolfgang Büchel writes:

Even though psi-phenomena apparently do not fit into the present categories of physics, certain analogies between parapsychology and modern physics are unmistakable….Leading quantum physicists such as Jordan or Pauli have reached a point where they no longer deny psi-phenomena a priori as something impossible, but rather take an unbiased look at the question of their reality. They are truly interested in the epistemological and philosophical questions posed by these phenomena. The fact that clairvoyance and precognition cross the categorical barriers of space and time, in any case, can no longer be accepted as sufficient reason to deny the possibility that the psi-phenomena may fit into a future body of physical categories.

To sum up: That which only recently appeared as the most unshakable and certain — time and matter — has become illusory. Instead, we have been given (and I use the word "given" quite deliberately) a new, more certain realization: that the cosmos and earth, organic and inorganic things, plants and animals and human beings are sound. Of course, you may say that they are vibrations; but in the overwhelming majority of cases they are vibrations in whole-number relationships. Vibrations in whole-number relationships, however, sound — whether within the human hearing range or above or below it.

In the second chapter, we became familiar with this ancient Zen koan:

If you blot out sense and sound — what do you hear?

Now we can vary the koan as follows:

If you blot out time and matter — what do you hear?

That is the actual question. We will do better ( and have a higher chance of success ) to try to solve it as a koan than to expect the solution from intellectual considerations. Take a look at the passage quoted from Chang-tzu on the epigraph page at the front of this book:

" The universe and I exist together, and all things and I are one. As all things are one, there is no need for further speech. But since I just said that all things are one, how can speech be not important?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Behind the divisible there is always something indivisible. Behind the disputable there is always something indisputable. You ask: What? The wise man carries it in his heart."