Hermeticism

The Historical Background of Hermeticism

Hermes & Thoth![]()

Hermeticism takes its name from the God Hermes Trismegistos or Thrice-Greatest Hermes. Trismegistos, in turn, was so-called because of His identification with the great Egyptian God of Wisdom and Magic, Thoth. Thôth is a Greek attempt to phonetically render Tehuti, the late antique form of the very ancient Egyptian name Djehuti. In an effort to express Tehuti’s majesty, when writing His name Egyptian scribes would often append the epithet Ao, Ao, Ao (literally "Great, Great, Great," meaning "Greatest"). Greeks and Greek-speaking Egyptians translated the Egyptian epithet as Trismegistos, also using it for ‘their’ Thoth — Hermes.![]()

![]() Just as Thoth was considered the all-wise font of sacred knowledge and author of all sacred books in Egypt, so in the Græco-Roman world, and later, in Renaissance Europe, Hermes Trismegistos was considered to be an unimpeachable authority on things sacred and author of the influential body of literature known as the Hermetica.

Just as Thoth was considered the all-wise font of sacred knowledge and author of all sacred books in Egypt, so in the Græco-Roman world, and later, in Renaissance Europe, Hermes Trismegistos was considered to be an unimpeachable authority on things sacred and author of the influential body of literature known as the Hermetica.![]()

Hermetic Syncretism![]()

Hermetism (the original Hermetic source from which the broader tradition of Hermeticism derives) was one of the many products of the meeting of the ancient Hellenic and Egyptian cultures in the centuries surrounding the beginning of the Common Era. Hermetism, described most simply, combined Egyptian and Greek theology, philosophy, and spiritual practice. But of course, it was not that simple.![]()

![]() Perhaps the principle reason the origin of Hermetism is complex is that it found its most fertile home in the great syncretic Græco-Egyptian metropolis of Alexandria, when that city was the cultural capital of the Mediterranean under the Pax Romana. Religious and philosophical wisdom flowed from many cultures into the city, the great spiritual Krater or Mixing Bowl which gave birth to the new synthesis of religion, philosophy, and practice which was Hermetism. Nominally Egyptian, and attributed to the Egyptian God Thoth in the guise of an enlightened ancient master, the Hermetic elixir was composed of ingredients from all the great Traditions active in Alexandria. To the millennia-rich stock of Egyptian religion, philosophy, and magic were added many elements from Greek Paganism (itself influenced throughout its development by Egypt, Anatolia, Phoenicia, and Syria), particularly the Mysteries and the philosophical schools of Platonism, Neo-Platonism, Stoicism, and Neo-Pythagorism; Alexandrian Judaism, with its Angelology, Magic, and deep reverence for the sacred Book; the many forms of Christianity (Gnostic and otherwise); Persian Zoroastrianism, with its deep concern with good and evil; as well as the new developments springing up alongside Hermetism and cross-fertilizing with it, such as Alchemy and Iamblichan Theurgy.

Perhaps the principle reason the origin of Hermetism is complex is that it found its most fertile home in the great syncretic Græco-Egyptian metropolis of Alexandria, when that city was the cultural capital of the Mediterranean under the Pax Romana. Religious and philosophical wisdom flowed from many cultures into the city, the great spiritual Krater or Mixing Bowl which gave birth to the new synthesis of religion, philosophy, and practice which was Hermetism. Nominally Egyptian, and attributed to the Egyptian God Thoth in the guise of an enlightened ancient master, the Hermetic elixir was composed of ingredients from all the great Traditions active in Alexandria. To the millennia-rich stock of Egyptian religion, philosophy, and magic were added many elements from Greek Paganism (itself influenced throughout its development by Egypt, Anatolia, Phoenicia, and Syria), particularly the Mysteries and the philosophical schools of Platonism, Neo-Platonism, Stoicism, and Neo-Pythagorism; Alexandrian Judaism, with its Angelology, Magic, and deep reverence for the sacred Book; the many forms of Christianity (Gnostic and otherwise); Persian Zoroastrianism, with its deep concern with good and evil; as well as the new developments springing up alongside Hermetism and cross-fertilizing with it, such as Alchemy and Iamblichan Theurgy.![]()

![]() Modern Hermeticism maintains this spiritual eclecticism, exploring and assimilating what is compatible and valuable from the Traditions with which it comes into contact, and sharing its own insights with other Traditions.

Modern Hermeticism maintains this spiritual eclecticism, exploring and assimilating what is compatible and valuable from the Traditions with which it comes into contact, and sharing its own insights with other Traditions.![]()

Hermetic Philosophies![]()

There was almost certainly not a single late antique Hermetic School; the conspicuous philosophical diversity in the surviving Hermetic treatises seems to preclude this. Instead the writings of the early Hermetists display the same independent spirit we recognize among members of the alternative spirituality community today. Probably they studied together in small groups, often with a single teacher and a group of students, on the model of the Hellenic philosophical schools. Some Hermetists, inspired by the Divine, inevitably added their own new insights and revelations to the Hermetic teachings. As do modern Hermeticists, the ancient Hermetists considered their Tradition a living, evolving Path, changing to reflect the results of their search for Divine Truth — not merely as an abstract philosophical concept, but as a very real, very personal part of their spiritual lives.![]()

Hermeticism Banished — and Returned![]()

When Christianity was adopted as the official state religion of the Roman Empire, Hermetism was suppressed along with the whole vast range of non-Christian religions, cults, sects, and schools that had flourished in the Empire, as well as the many forms of Christianity now perceived as competitors with the wealthy and powerful Church of Rome.![]()

![]() Yet, against all odds, some few of the Hermetic books dealing with philosophy, mysticism, and particularly those dealing with Alchemy, were preserved through the long Middle Ages by scholars and collectors in Greek Byzantium.

Yet, against all odds, some few of the Hermetic books dealing with philosophy, mysticism, and particularly those dealing with Alchemy, were preserved through the long Middle Ages by scholars and collectors in Greek Byzantium.![]()

![]() The group of texts now known as the Corpus Hermeticum finally returned to the Latin West during the Italian Renaissance when the Florentine philosopher prince Cosimo de Medici obtained a set of manuscripts from one of his agents in the Greek East and commissioned the scholar, priest, magician, and philosopher Marsilio Ficino to translate the Corpus into Latin.

The group of texts now known as the Corpus Hermeticum finally returned to the Latin West during the Italian Renaissance when the Florentine philosopher prince Cosimo de Medici obtained a set of manuscripts from one of his agents in the Greek East and commissioned the scholar, priest, magician, and philosopher Marsilio Ficino to translate the Corpus into Latin.![]()

![]() Yet these were, after all, Pagan texts. How was it that these Pagan scriptures could be even passably acceptable in the very Christian world of Renascimento Italy? The solution was in the form of a fortuitous mistake. Two centuries before the advent of European textual criticism, Ficino and the other Renaissance philosophers, magicians, and artists who studied the Hermetic texts accepted the largely legendary pseudo-historical milieu claimed for themselves by the Hermetica (much as Biblical scholars for centuries uncritically accepted late pseudepigraphic texts as ancient history) and believed that the Hermetic texts were far more ancient than they actually were. Ficino therefore believed that Hermetic philosophy was an ancient forerunner of Christianity rather than its contemporary. So when the Hermetic texts showed influence from Jewish or Christian myth, this was understood not as the syncretism of a late age, but as the prophetic prefiguring of an earlier one. As such, the Hermetica could be viewed as predicting the supposed triumph of Christianity and their obvious Paganism forgiven, just as the Hebrew "Old Testament" could justifiably, in spite of its Judaism, be studied by Christians for its Messianic prophecies, all of course applied to Jesus by the Church.

Yet these were, after all, Pagan texts. How was it that these Pagan scriptures could be even passably acceptable in the very Christian world of Renascimento Italy? The solution was in the form of a fortuitous mistake. Two centuries before the advent of European textual criticism, Ficino and the other Renaissance philosophers, magicians, and artists who studied the Hermetic texts accepted the largely legendary pseudo-historical milieu claimed for themselves by the Hermetica (much as Biblical scholars for centuries uncritically accepted late pseudepigraphic texts as ancient history) and believed that the Hermetic texts were far more ancient than they actually were. Ficino therefore believed that Hermetic philosophy was an ancient forerunner of Christianity rather than its contemporary. So when the Hermetic texts showed influence from Jewish or Christian myth, this was understood not as the syncretism of a late age, but as the prophetic prefiguring of an earlier one. As such, the Hermetica could be viewed as predicting the supposed triumph of Christianity and their obvious Paganism forgiven, just as the Hebrew "Old Testament" could justifiably, in spite of its Judaism, be studied by Christians for its Messianic prophecies, all of course applied to Jesus by the Church.![]()

![]() Because of this mistaken assumption of prophetic antiquity, conjoined with the self-proclaimed Orphic Ficino’s simultaneous re-interpretation of Magic in a much brighter and less controversial form than that of the Mediæval period (which itself contained many clandestinely preserved elements of Hermetism), the new figure of the Hermetic Renaissance Magus entered the cultural consciousness of the era. Ficino’s ‘Natural Magic’ moved out of the shadows of the grimoires and once more into the light of general philosophical and theological consideration. A student at Ficino’s Florentine Platonic Academy, the brilliant and daring enfant terrible Count Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, added the crucial catalytic element of the Jewish Qabalah to the new Pagan-Christian Hermetic amalgam, and transformed Hermetism forever. It is here that Hermeticism was born of ancient Hermetism, once more entering into a syncretic union, this time with Christianity, Renaissance Neo-Classicism and Humanism, Natural Magic, and Qabalah.

Because of this mistaken assumption of prophetic antiquity, conjoined with the self-proclaimed Orphic Ficino’s simultaneous re-interpretation of Magic in a much brighter and less controversial form than that of the Mediæval period (which itself contained many clandestinely preserved elements of Hermetism), the new figure of the Hermetic Renaissance Magus entered the cultural consciousness of the era. Ficino’s ‘Natural Magic’ moved out of the shadows of the grimoires and once more into the light of general philosophical and theological consideration. A student at Ficino’s Florentine Platonic Academy, the brilliant and daring enfant terrible Count Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, added the crucial catalytic element of the Jewish Qabalah to the new Pagan-Christian Hermetic amalgam, and transformed Hermetism forever. It is here that Hermeticism was born of ancient Hermetism, once more entering into a syncretic union, this time with Christianity, Renaissance Neo-Classicism and Humanism, Natural Magic, and Qabalah.![]()

![]() The resulting vigorous Hermetic influence spreading out from the court of the Medicis and the Academy of Ficino clearly served as one of the most potent inspirations for the spiritual, artistic, and scientific renewal of the Renaissance.

The resulting vigorous Hermetic influence spreading out from the court of the Medicis and the Academy of Ficino clearly served as one of the most potent inspirations for the spiritual, artistic, and scientific renewal of the Renaissance.![]()

Hermeticism as Western Esoteric Tradition![]()

In addition to the religious and philosophical traditions already mentioned, Hermeticism has of course included the beauty of Rosicrucianism since the 17th century, and has illuminated the symbolic ritual of Freemasonry since the 18th. It was the motivating force behind the foundation of the most influential esoteric schools of the fin de siecle — Theosophy, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and the Martinism of Papus — and the great Occult Revival to which they gave birth, and has strongly influenced the 20th-century Pagan Renaissance.![]()

![]() The profoundly influential work of psychologist C.G. Jung may also reasonably be considered a Hermetic legacy with its Alchemical symbolism, god-like archetypes, and concern with the subtle realms of the psyche. Letters survive in which a correspondent reported to Jung that she had come across the concepts of Animus and Anima in the 18th-century British novel Tristram Shandy, and asked Jung if he had been inspired by the book. He replied that he had been unaware of the occurrence of the ideas in the book and could only assume that Sterne, the author, had been privy to the teachings of the esoteric — probably Rosicrucian — circles of his day, clearly indicating Jung’s acknowledgement of his own indebtedness to the Hermetic Tradition.

The profoundly influential work of psychologist C.G. Jung may also reasonably be considered a Hermetic legacy with its Alchemical symbolism, god-like archetypes, and concern with the subtle realms of the psyche. Letters survive in which a correspondent reported to Jung that she had come across the concepts of Animus and Anima in the 18th-century British novel Tristram Shandy, and asked Jung if he had been inspired by the book. He replied that he had been unaware of the occurrence of the ideas in the book and could only assume that Sterne, the author, had been privy to the teachings of the esoteric — probably Rosicrucian — circles of his day, clearly indicating Jung’s acknowledgement of his own indebtedness to the Hermetic Tradition.![]()

![]() Today, as we draw near the dawn of a new millennium, many groups — such as the Hermetic Fellowship — are the inheritors of the still vibrant Hermetic Current.

Today, as we draw near the dawn of a new millennium, many groups — such as the Hermetic Fellowship — are the inheritors of the still vibrant Hermetic Current.

The Corpus Hermeticum and other Hermetica

Topics Addressed by the Hermetica![]()

Hermeticism has always valued not only oral teaching, but spiritual knowledge passed on by teachers through the medium of books. The original Hermetic books, those attributed to Hermes Trismegistos, are called the Hermetika (usually Latinized as Hermetica). They address a wide range of topics, including discussions of the cosmic principles, the nature and orders of Being and beings, the human yearning to know the Divine, mysticism, magic, astrology, alchemy, and medicine. Scholars generally place the individual texts of the Hermetica, somewhat arbitrarily, in one of two camps: the ‘philosophical’ and religious Hermetica, or the ‘technical’ — that is, magical or theurgic — Hermetica.![]()

Dating of the Hermetica![]()

The main philosophical Hermetic texts which have come down to us are contained in the Corpus Hermeticum, a collection of approximately 17 treatises originally composed in Egypt and written in the Greek language. The exact date for the composition of the texts is unknown, but most scholars place at least the main texts of the Corpus in the second or third centuries CE. Technical Hermetica range more broadly, and are tentatively dated to a period spanning the first century BCE to the fourth century CE. It is quite possible, however, that at least some of the texts were based on significantly earlier models. Inscriptions prove that Hermes Trismegistos was already a name for Thoth at Saqqara as early as the second century BCE.![]()

Other Hermetica![]()

In addition to the texts contained in the Corpus there are many other writings ascribed to Hermes Trismegistos, and as such, are by definition, Hermetica. Among these are the famous Asclepius (originally entitled The Perfect Discourse), which is both philosophical and magical, and texts such as The Ogdoad Reveals the Ennead, which is a philosophical and mystical Hermetic text not in the original Byzantine anthology translated by Ficino, but added to the Hermetic collection after being discovered in the Gnostic library at Nag Hammadi. There are also a significant number of the Græco-Egyptian Magical Papyri said to be the work of Hermes Trismegistos. It may even be, given Thoth’s position as Great Divine Magician, that the first Hermetica were not the philosophical texts such as those in the Corpus Hermeticum and the Nag Hammadi find, but were technical, that is, magical texts. The structure of the Hermetic texts, whether philosophical or technical, are often in the form of dialogues between a teacher and one or more students.![]()

The Hermetica as Sacred Texts![]()

The Hermetica form one of the bases for the philosophy, beliefs, and values of modern Hermeticism, along with many other texts of the Western Tradition. While the Hermetica are considered sacred texts in that they provide important information on matters of a sacred nature and can be extremely profound and valuable guides on the spiritual path, neither they nor any other text are considered infallible or without contradiction.

The Beliefs of Hermeticism

The Perennial Philosophy![]()

The Hermeticism of the Hermetic Fellowship is also called the Western Esoteric Tradition, and embraces that essential outpouring of the Light known as the Philosophis Perennis, the Prisca Theologia, the Wisdom Tradition, and the Ageless Wisdom. Esoteric legend holds that this is a body of spiritual teachings that have been passed down through the millennia from generation to generation, teacher to student. The Tradition is said to have been the inner impetus for the blossoming of arts and sciences in many ages and the common inspiration of that which is truest in the world’s religions.![]()

![]() As we’ve seen even in the extremely brief history above, in the case of Hermeticism, the legend is at least partly true. While Hermeticism came into its own in the first millennium CE, it drew on yet more ancient Egyptian, Greek, and other traditions as its sources. In turn, it passed that knowledge on to most of the major Western esoteric movements of the past two thousand years. Furthermore, Hermeticism truly has inspired both artists and scientists throughout that period, from Botticelli to Dee to Newton to Cezanne.

As we’ve seen even in the extremely brief history above, in the case of Hermeticism, the legend is at least partly true. While Hermeticism came into its own in the first millennium CE, it drew on yet more ancient Egyptian, Greek, and other traditions as its sources. In turn, it passed that knowledge on to most of the major Western esoteric movements of the past two thousand years. Furthermore, Hermeticism truly has inspired both artists and scientists throughout that period, from Botticelli to Dee to Newton to Cezanne.![]()

Characteristics of Hermeticism![]()

The Hermetic Tradition is not a single dogmatic school of thought or one particular spiritual system. Rather, it is a living body of knowledge and practice that springs from a common root while bearing a variety of blossoms. As in the original Hermetic schools, a stimulating diversity of views and experiences may be found in contemporary Hermeticism, although there are some broad characterizations that can be made.![]()

![]() The following particularly apply to the Hermeticism of the Hermetic Fellowship. Each of these characteristics has legitimate historical precedent and would be shared by many, but certainly not all, Hermetic groups operating today.

The following particularly apply to the Hermeticism of the Hermetic Fellowship. Each of these characteristics has legitimate historical precedent and would be shared by many, but certainly not all, Hermetic groups operating today.![]()

Eclecticism![]()

Just as Alexandrian Hermeticism drew on a wide variety of religious and philosophical traditions, so modern Hermeticism explores a broad range of spiritual paths within the Hermetic, or Western Esoteric, Tradition. For the Hermetic Fellowship, these paths include — but are not limited to — the Ancient Mystery Religions, Qabalah, Alchemy, Rosicrucianism, Gnosticism and other types of esoteric Christianity, Theurgy, Wicca and Neo-Paganism, and the Grail Quest.![]()

![]() As a guiding metaphor, the Hermetic Fellowship has adopted the Pharos, the Lighthouse of Alexandria which shone its Light upon all the many different spiritual, magical, and religious paths which came together in that city, cross-fertilizing each other and producing an illuminating spiritual flowering. Accepting this multiplicity means that Hermetics must be able to entertain the paradoxical idea of multiple realities. Spiritual paradox is considered a Mystery to be understood, not necessarily a contradiction to be ruled out.

As a guiding metaphor, the Hermetic Fellowship has adopted the Pharos, the Lighthouse of Alexandria which shone its Light upon all the many different spiritual, magical, and religious paths which came together in that city, cross-fertilizing each other and producing an illuminating spiritual flowering. Accepting this multiplicity means that Hermetics must be able to entertain the paradoxical idea of multiple realities. Spiritual paradox is considered a Mystery to be understood, not necessarily a contradiction to be ruled out.![]()

![]() Although by definition we limit ourselves to exploring the Western Traditions, we honor all spiritual Paths, in so far as each contains a ray of that Divine Light which we seek.

Although by definition we limit ourselves to exploring the Western Traditions, we honor all spiritual Paths, in so far as each contains a ray of that Divine Light which we seek.![]()

Spiritual Curiosity![]()

Hermetics are Seekers — Seekers of Divine Truth, Seekers of Wisdom, Seekers of Understanding, Seekers of Gnosis. Hermetic spiritual curiosity encourages openness and tolerance of the ways and spiritual paths of others. This curiosity may be partially satisfied through books. As a literate and literary tradition, Hermeticism holds that as seekers we can benefit through the recorded experiences and insights of others — as well as through the mediation of a living teacher and/or a group of fellow seekers.![]()

![]() But it is not enough to simply read about the spiritual. We will gain little without genuine, personal experience. Therefore, while we highly recommend personal study and teaching, we also stress the irreplacable value of participation in the spiritual through ritual, meditation, and other spiritual practices. The religious devotion of one’s choice will prove extremely valuable in one’s growth as well.

But it is not enough to simply read about the spiritual. We will gain little without genuine, personal experience. Therefore, while we highly recommend personal study and teaching, we also stress the irreplacable value of participation in the spiritual through ritual, meditation, and other spiritual practices. The religious devotion of one’s choice will prove extremely valuable in one’s growth as well.![]()

Polytheism & Ultimate Monotheism![]()

Since it has its roots in the ancient Pagan traditions, we see Hermeticism as a generally polytheistic approach to spirituality. The Divine makes Itself known by many names and wears many faces. Many Goddesses and Gods — particularly those honored by the cultures that gathered at Alexandria under the Light of the Pharos — are important to Hermeticism. Yet underlying and uniting this polytheism, we posit an ultimate Divine Unity, an ultimate monotheism.![]()

![]() This concept extends to the Hermetic understanding of the Universe. The Universe is multiform and diverse, yet ultimately united in the One. Thus we can seek and discover the hidden connections leading to the revelation of the Unity behind the apparent diversity of the world. Hermetic Qabalah is one model for this: while each of the Sephiroth is an expression of the diversity of the Divine, all emanate from and are united in Kether, which Unity Itself is ultimately an Emanation from the Unmanifest En Soph.

This concept extends to the Hermetic understanding of the Universe. The Universe is multiform and diverse, yet ultimately united in the One. Thus we can seek and discover the hidden connections leading to the revelation of the Unity behind the apparent diversity of the world. Hermetic Qabalah is one model for this: while each of the Sephiroth is an expression of the diversity of the Divine, all emanate from and are united in Kether, which Unity Itself is ultimately an Emanation from the Unmanifest En Soph.![]()

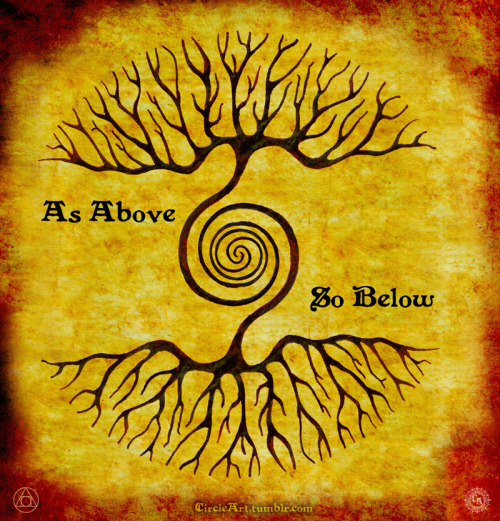

As Above, So Below![]()

Hermetics consider the Divine to be both immanent and transcendent. The Divine is within all things in the manifested Universe (notably including ourselves), and beyond them as well. Because of the interconnection between ‘above’ and ‘below,’ what happens on a spiritual level has consequences in the material. Conversely, what happens in the material can have consequences in the spiritual.![]()

![]() Creating equilibrium between all these things — matter and spirit, body and soul, within and without, night and day, in fact, all polarities — is pivotal to the spiritual Work of the Hermetic. Balance is the key to growth.

Creating equilibrium between all these things — matter and spirit, body and soul, within and without, night and day, in fact, all polarities — is pivotal to the spiritual Work of the Hermetic. Balance is the key to growth.![]()

All is Divine![]()

Since the Divine is in all things, all is Divine. Through contemplation and understanding of the Universe, including ourselves, through prayer, aspiration, and gnosis (or sacred ‘knowing’), human beings can become more ‘god-like’ and eventually come to reunite with the Divine. Many Hermetics do not believe this goal can be achieved during a single lifetime, and some hold that this ideal is not fully attainable while in the physical body. Attitudes toward reincarnation vary.![]()

![]() In the ancient Hermetica, you will find two different attitudes toward the Universe, which may be distinguished (as by Frances Yates) as optimistic and pessimistic. The optimistic attitude posits a Divine and basically good Universe — although it recognizes the many trials we and all things undergo. The pessimistic attitude sees matter as a distraction from spirit and because of this, qualitatively evil. The Hermeticism of the modern Fellowship is decidedly of the optimistic school.

In the ancient Hermetica, you will find two different attitudes toward the Universe, which may be distinguished (as by Frances Yates) as optimistic and pessimistic. The optimistic attitude posits a Divine and basically good Universe — although it recognizes the many trials we and all things undergo. The pessimistic attitude sees matter as a distraction from spirit and because of this, qualitatively evil. The Hermeticism of the modern Fellowship is decidedly of the optimistic school.![]()

Nature Reveals the Divine![]()

To the modern Hermetic, Nature is the Divine teacher, the Revealer of the Mysteries. A Rosicrucian motto puts it this way, "Art is the Priestess of Nature." Thus, in order to accomplish his or her spiritual Art, the Hermetic must also serve Nature as a Priest or Priestess. The physical world is the manifestation or vessel of Divine Power and Love, and we are uniquely entrusted with caring for that vessel.![]()

![]() There is an esoteric tradition that when Adam (i.e.,Humanity) fell, in one sense Nature fell with him. By redeeming Adam through our own spiritual growth and development, we also redeem Nature. The converse is also true: by redeeming Nature, we redeem ourselves. This idea provides one basis for Hermetic environmentalism.

There is an esoteric tradition that when Adam (i.e.,Humanity) fell, in one sense Nature fell with him. By redeeming Adam through our own spiritual growth and development, we also redeem Nature. The converse is also true: by redeeming Nature, we redeem ourselves. This idea provides one basis for Hermetic environmentalism.![]()

![]() In return for our honor and our care, Nature reveals Her Divine Self as an infinitely profound symbol for the spiritual journey. In the rhythms of the Earth and the cycles of the Sun, the Moon, and the Planets, the awesome structure of the Universe, the complementary miracles of birth and death, the Hermetic finds the Divine unveiled — and celebrates.

In return for our honor and our care, Nature reveals Her Divine Self as an infinitely profound symbol for the spiritual journey. In the rhythms of the Earth and the cycles of the Sun, the Moon, and the Planets, the awesome structure of the Universe, the complementary miracles of birth and death, the Hermetic finds the Divine unveiled — and celebrates.![]()

The Will to the Light![]()

Human beings have a unique place in the Divine pattern because of our Will. We have the ability to aspire to the Divine, and this we must do in order to attain to the Divine. A seeker must want to find. A philosopher must desire to know. And furthermore, she or he must use the power of Will to accomplish this. Hermeticism takes an optimistic view of the individual human being as well. Encouraged by Divine Love and through the use of the considerable human power of desire and Will, everyone has the ability to achieve union with her or his Higher Self, and eventually to reunite with the Divine.![]()

Access to the Subtle Realms![]()

Human beings have the ability to access the non-physical realms — the psychic, the mental, the spiritual. Furthermore, this is a natural, innate ability that can be more fully developed through a variety of spiritual techniques. One way to access the non-physical is through the practice of Theurgy, or working with the Divine through ritual. Ritual can be a particularly powerful practice in the Quest, as it can combine a variety of individual psychospiritual techniques into a powerful whole to put us in touch with the non-physical realms. As stated above, working in Theurgic harmony with the Divine, and through the law of As Above, So Below, works in the non-physical affect the physical — and vice versa.![]()

The Great Work![]()

The idea that humankind has fallen away from a previous state in which we were more blessed and more unified with the Divine is common to many religions and philosophies. Versions of the concept are to be found in the Egyptian, Greek, Gnostic, and Hebrew mythologies that are components of the Hermetic Current. Hermetics do not see the fall from unity as evil or as a punishment. Instead, it was necessary for spiritual growth. Just as a young person must leave home and truly experience life in order to grow and mature, so humanity as a whole had to ‘fall’ into experience. But our journey is not complete until we eventually return home and unite with the Divine once more for healing and regeneration.![]()

![]() The work that each Hermetic is called to undertake, though it is sometimes called the Tiqqun,, the Restoration, is not simply regaining our blessed, pre-fall state of Unity; it is the attainment of something new, for we -- and all of reality -- have been metamorphosized by our entry into the great cocoon of incarnation. When we return to Eden, it will not be simply the Garden we once left, but in the midst of the Garden will stand the Holy City, the highest attainment of the human spirit in creative Union with the Divine. This return to a new and transformed Unity with the Divine is the ultimate goal of the Hermetic work. This process is called both the Great Work and the Royal Art. It is the finding of the Stone of the Philosophers, True Wisdom, Perfect Happiness, the Summun Bonum.

The work that each Hermetic is called to undertake, though it is sometimes called the Tiqqun,, the Restoration, is not simply regaining our blessed, pre-fall state of Unity; it is the attainment of something new, for we -- and all of reality -- have been metamorphosized by our entry into the great cocoon of incarnation. When we return to Eden, it will not be simply the Garden we once left, but in the midst of the Garden will stand the Holy City, the highest attainment of the human spirit in creative Union with the Divine. This return to a new and transformed Unity with the Divine is the ultimate goal of the Hermetic work. This process is called both the Great Work and the Royal Art. It is the finding of the Stone of the Philosophers, True Wisdom, Perfect Happiness, the Summun Bonum.![]()

![]() This journey home may be understood as a process of renewing our links with the Divine through a system whose keys are the patterns of Nature. Each link is represented by an initiation. Different schools follow different natural patterns. For example, some might use a series of initiations based on the steps of an Alchemical operation; another might base their initiations on the development of the psyche and spirit; yet another on the cycles of the Moon.

This journey home may be understood as a process of renewing our links with the Divine through a system whose keys are the patterns of Nature. Each link is represented by an initiation. Different schools follow different natural patterns. For example, some might use a series of initiations based on the steps of an Alchemical operation; another might base their initiations on the development of the psyche and spirit; yet another on the cycles of the Moon.![]()

![]() Furthermore, instead of a spiritual journey that rejects all things material in order to re-attain the spiritual, the goal of the Hermetic is to embrace and balance all things. Hermeticism may be described as a poetic rather than an ascetic mode of Attainment. Hermes Trismegistos, quoting the Divine Mind, tells us:

Furthermore, instead of a spiritual journey that rejects all things material in order to re-attain the spiritual, the goal of the Hermetic is to embrace and balance all things. Hermeticism may be described as a poetic rather than an ascetic mode of Attainment. Hermes Trismegistos, quoting the Divine Mind, tells us:![]()

| Make yourself grow to immeasurable immensity, outleap all body, outstrip all time, become eternity, and you will understand God. Having conceived that nothing is impossible to you, consider yourself immortal and able to understand everything, all art, all learning, the temper of every living thing. Go higher than every height and lower than every depth. Collect in yourself the sensations of all that has been made, of fire and water, dry and wet; be everything at once, on land, in the sea, in heaven; be not yet born, be in the womb, be young, old, dead, beyond death. And when you have understood all these things at once — times, places, things, qualities, quantities — then you can understand God. |