Submitted by Oscar on

Submitted by Oscar on

Image by PublicDomainPictures from http://Pixabay.com

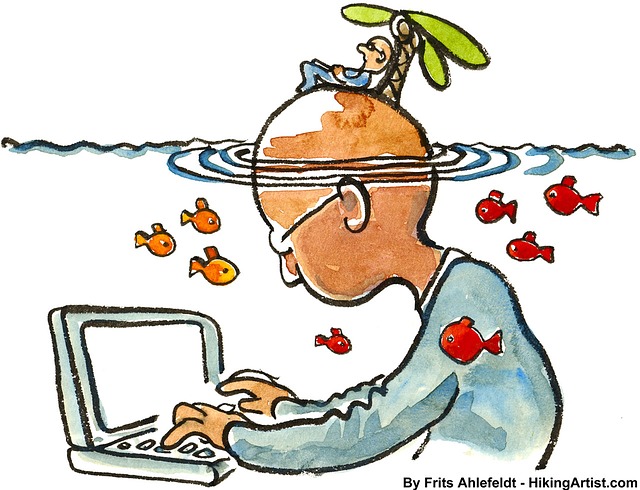

To be human is to procrastinate.

Exceptions exist, but most of us can identify at least one area of our imperfect lives (whether it’s our health, home, work, or relationships), where, for no justifiable reason, we routinely delay doing that thing (or series of small thingys) that would improve the present moment or future.

Procrastination also appears to be as old as we are—academics have traced a history of philosophers grappling with the problem—so relying on a few hacks to deal with it seems naive. People love hacks, but they’re really only handy for treating procrastination as a symptom, the way small nudges—like hiding the cookie jar—can help people stick to a diet, without, arguably, changing their fundamental relationship with food.

Our guide, therefore, combines hacks with suggested tactics for designing your own more holistic approach to beating procrastination, one that examines all the deeper dynamics at work—the fear, the automatic coping strategies, the self-deception—when you put things off. All we ask is you…

1. Take the first (micro) step

Boom. You’ve done it. Not only did you click into this story, but you’ve also begun reading the first “tip,” rather than pinging the link to your Pocket or Evernote list to read later. Making that oh-so-tiny first move is an evidence-backed strategy for beating procrastination; the trick is setting the threshold for completion low—so low that the hedonist in you, who would rather feel good now and deal with real stuff later, won’t put up a fight.

Tim Pychyl, a psychologist and director of the Procrastination Research Group at Carleton University, in Ottawa, Canada, says that his group tested this approach in a small study and “found that once students got started, they appraised a task as less difficult and less stressful, even more enjoyable than they had thought,” he explains in an email to Quartz. “They said things like ‘I don’t know why I put it off, because it’s not so bad,’ and ‘I could have done a better job if I got started earlier.’”

2. Manage your emotions, not only your time

One common harbinger of oncoming procrastination is the belief that you should wait until you’re in the right mood to get something done. It’s a trap.

Joseph Ferrari, a professor of psychology at DePaul University in Chicago, has found that the “I’m not in the mood to do X” argument, which we’re all familiar with, can lead to a vicious cycle. The Atlantic once called it the “procrastination doom loop,” and described the stages: “I’ll do it later!” becomes “Ugh, I’m being so unproductive,” which turns into “Maybe I should think about starting this task…,” leading directly to “but I’m in the wrong mood to do it well,” so “I’ll do it later!” And so on.

The truth is, tossing aside a task because you’re “not in the mood” is actually a way of externally regulating your emotions—perhaps a fear of failure, of disappointing others, of losing some self-esteem, of not being perfect, says Fuschia Sirois, a psychologist and lecturer at the University of Sheffield in the UK. You may believe that procrastination is a time management issue, but really, “it’s just a way of coping with emotions that you’re ill-equipped to cope with,” she says. The dark feelings can be off-putting enough to be paralyzing, to send you looking for anything else you can do besides the task at hand, a reaction that’s often knee-jerk and unexamined.

Sirois suggests reflecting on the real reason that you’re procrastinating, and turning to emotional regulation tactics—which could include reframing the way you see a situation (psychologists call it cognitive reappraisal), or naming the emotion you’re experiencing (labelling)—to deal with the underlying feelings that are triggering procrastination. Research has suggested that people with more developed abilities at regulating their emotions, and in particular those who can tolerate the unpleasant ones, are less likely to procrastinate. In other words, you may need a therapist, or you may need to figure out how to be your own therapist.

3. Name your delay: Is it really procrastination?

One easy solution to cutting down on all the procrastination in your life is to reclassify any delays that aren’t actually procrastination, thus clarifying your perspective on the problem. It could lift some unnecessary weight.

Delays come in all forms, and some are what Pychyl calls “sagacious delays.” They might give a person room to gather more information or get the sleep needed to refresh an overworked mind. Other delays are inevitable and may stem from other more pressing roles you play in your life, says Pychyl.

Consider the taxonomy of delays that Mohsen Haghbin, one of Pychyl’s former students, identified:

- Inevitable delays, arising when one’s schedule is overloaded or a crisis related to an obligation (as a parent, for example) knocks a person off track

- Arousal delays, when a person delays a task because they enjoy the pressure of doing something at the last minute

- Hedonistic delays, when a person chooses doing something instantly gratifying and pleasurable over the task at hand

- Delays due to psychological problems, such as grieving or another mood or mental health condition, whether chronic or acute

- Purposeful delays, when a person needs to, say, think about something before writing about it

- Irrational delays, which are inexplicable to the procrastinator and often fueled by fear and anxiety

In practice, these categories are not mutually exclusive.

Correctly labelling a delay matters, because you can’t defeat an enemy if your image of it is in vague or muddied. Sometimes you may be intentionally pushing something into the future—let’s say postponing your delivery of a creative project— and calling it procrastination, when what you’re actually doing is allowing yourself time to think. But calling it “productive procrastination” could easily lead to real procrastination, Pychel theorizes, because, by its definition, procrastination impedes productivity.

Many people say they have made procrastination work for them, such as Tim Urban, author of the “Wait But Why” blog and a master procrastinator. Arguably, Leonardo Da Vinci did the same. According to the taxonomy above, however, what such people may actually have figured out for themselves is the value of arousal or purposeful delay. All the power to them, but intentional delays can worsen anxiety in those prone to it. Importantly, at least according to Pychyl, they’re not necessarily procrastinators in the truest sense and they likely don’t have to deal with the fallout from real procrastination. At work, for instance, chronic procrastination has been associated with lower salaries and lower rates of employment.

4. Practice “structured” procrastination

In 1996, John Perry, a Stanford University professor of philosophy, gave the procrastinators of the world a gift: a concept called “structured procrastination.” (He has since written a book on the topic.) To procrastinate with structure involves putting the task that’s most daunting and somewhat urgent near the top of your list, but keeping your list filled with other equally valuable tasks that are less daunting to you.

Since procrastinators avoid whatever is near the top of the their list, that’s where he suggests putting your most important task, and taking advantage of your urge to avoid it to tackle all the less important but still-valuable must-dos on your agenda. So, instead of getting next-to-nothing done as you put off writing that first draft of your looming presentation, you attack your messy office desk with cheerful fervor. As a bonus, your inner maverick—the one who wants you not to be such a mindless slave to your obligations— will feel acknowledged.

Perry also suggested padding your list of to-dos with the minor accomplishments you probably would have pulled off anyway, like “make coffee” or “shut off alarm,” just to give yourself those dopamine hits from tiny wins.

He wrote in his original essay on the topic:

Procrastinators often follow exactly the wrong tack. They try to minimize their commitments, assuming that if they have only a few things to do, they will quit procrastinating and get them done. But this approach ignores the basic nature of the procrastinator and destroys his most important source of motivation. The few tasks on his list will be, by definition, the most important. And the only way to avoid doing them will be to do nothing. This is the way to become a couch potato, not an effective human being.

It’s all a mind game you play with yourself, but proponents say it works.

5. Time travel to your future self

When a New Year’s resolution fails, we rarely hold a back-of-the-brain, post-mortem meeting to examine why. If we did, we’d often discover that we’d made a mistake when we imagined the future: we saw it as different from today, free of the burdens that make exercise or organizing our files feel so totally impossible to achieve this week. But we don’t ask why Monday would be any different.

“We believe this future me of tomorrow or next week will have more energy, more willpower to follow through on this task that feels threatening to me,” says Sirois, “but we don’t really change that much in that time frame.” It’s a ruse that only leads to more stress, she adds.

Eve-Marie Blouin-Hudon, a psychology researcher at Carleton University, has developed a guided visualization exercise—to be practiced daily for 10 minutes—to help people feel more connected to their future self, to see that they are largely one and the same, and to thus be kinder to that person. To begin, you would choose the area in which you most need to stop procrastinating. Then begin to imagine yourself at a certain “deadline” time in the future, and get specific about the details: Where are you? What are you wearing? How do you feel? What words do you see in an email to you about this task? Although Blouin-Hudon’s script was written for students, it can serve at a blueprint for a personalized exercise.

We have a wonderful ability to “see” the past, present, and future, so why not use it, says Blouin-Hudon. Her work and that of others have suggested that shoring up one’s sense of “future-self continuity” can lead to less procrastination.

6. Make plans to work around the “The hell with it” effect

Once you’re committed to not procrastinating, you may still encounter moments when, facing an unexpected turn of events, you’ll be tempted to return to your old friend, your trusted escape, procrastination.

For instance, you’re planning to cycle to work, but when you open the garage door, you find that it’s raining, writes Thomas Webb, another psychologist at University of Sheffield, in his Psychology Today blog, “The Road To Hell.” Suddenly your will power is stretched, and your good intention is vulnerable to collapsing under what Webb calls “‘the hell with it’ effect.” As in “The hell with it. I can ride to work tomorrow.”

But, he explains, your intentions will have a fighting chance if you have enacted an “if-then” plan, a specific type of behavior change technique, developed by psychologist Peter Gollwitzer. The “if-then” method ensures that you’ve spent some time thinking about what headwinds you might encounter and how you’ll react to them. Rather than give up when a challenge arises, writes Webb, “the person would quickly and relatively automatically think about how good they will feel about themselves if they cycle and find themselves rolling down the road looking forward to these feelings.”

Behavior change, as a category of study, is loaded with techniques like this, Webb points out. Among the dozens of options, the if-then plan has the most evidence to suggest that it’s durable enough to protect a commitment during a stress test.

It can pay to attend to your physical and mental environment, too, to minimize the number of critical moments that might possibly be encountered. If your mind perceives a silently vibrating phone as a cue to start scrolling through Instagram, turn the appliance off. (Seems obvious, but how often do we do it?) If your colleague’s mood feels contagious and counterproductive, create some distance.

7. Avoid berating oneself

Negative emotions can be motivating, until they’re not. When you’re so immersed in a crappy feeling, like shame or fear, you can’t take an objective view of the situation, says Sirois. “When procrastinators feel bad, they’re feeling bad not just about the things they’re currently procrastinating on, but they’re remembering all the times they procrastinated before,” Sirois explains, “so it feeds back into feeling negative, which feeds back into wanting to avoid whatever the task is all together.”

A range of exercises exist to help a person recognize and become less controlled by self-defeating emotions, she says, whether through forgiveness, or more subtly, self-compassion, her focus of academic research. For instance, you might first recall a past incident when you procrastinated, and life was not okay in the end. Then write a note to yourself, as if you were writing to a friend, reassuring that person that what they did was not immoral or inexcusable. “We’re a lot kinder to other people who are struggling than we are to ourselves,” she adds. “We all default to self-critical.”

Sirois’s experiments suggest that normalizing your past mistakes this way seems to “brings down the threshold of those emotions, so that you can get on with things, rather than having to deal with the way you’re feeling.”

Simply tell yourself, “Look, you were not the first person to procrastinate,” she says, “and you won’t be the last.”

Lila MacLellan

- 425 reads