Submitted by Krishna on

Submitted by Krishna on

Derivative Images

According to John Powers - Professor of Religious Studies, Deakin University:

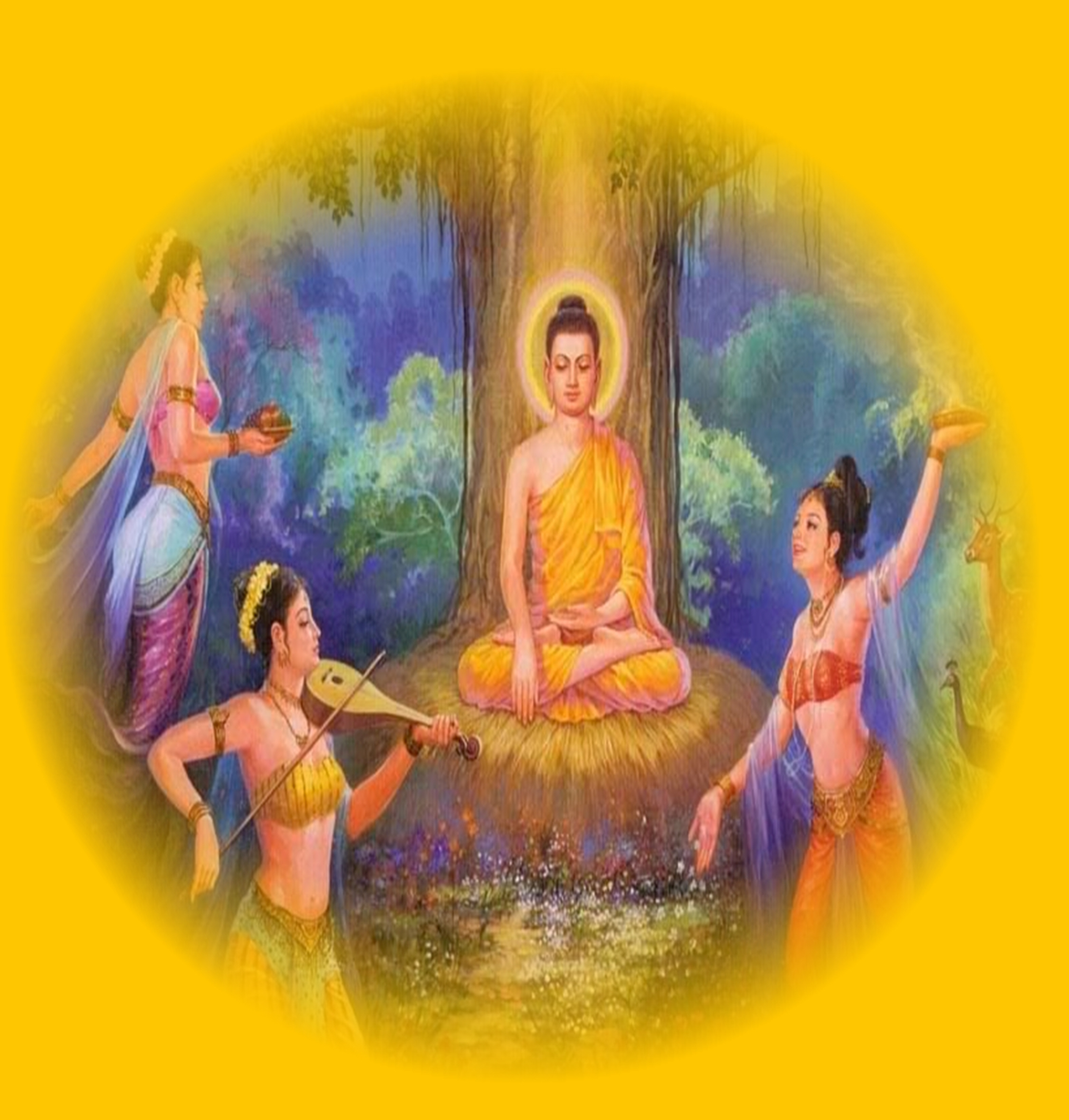

"Despite the fact that Prince Siddhārtha Gautama would grow up to become a religious leader and found a monastic order that enjoined strict celibacy for its members, during his teens he is commonly depicted as residing in the women’s quarters of his father’s palace and enjoying sensual pleasures with a large harem of beautiful women. His father, King Śuddhodana, feared that his son might be inclined toward religious pursuits, and so he provided an environment rich in physical enjoyments: sporting activities, archery contests, and alluring women skilled in music and lovemaking. The Deeds of the Buddha (Buddha-carita) describes the setting: “the women delighted him with their soft voices, enticements, playful intoxications, sweet laughter, curvings of eyebrows and sidelong glances. Then a captive to the women, who were skilled in the arts of love and tireless in sexual pleasure, he did not descend from the palace to the ground, just as one who has won paradise by his merit does not descend to earth from the heavenly abodes.” (Buddha-carita: 16)

The Extensive Sport claims that this was necessary because all past buddhas also had large harems, and part of the narrative sequence of a future buddha’s life is a period in the women’s quarters during which he engages in prodigious amounts of sexual activity. Behind this is a common notion in ancient Indian sources that celibacy is a core component of the path to liberation, and a voluntary decision to abstain from sex results in great merit and psychic power. But only those who are fully capable of performing sexually can reap such benefits. Moreover, it is important for the story’s conceptual logic that the future Buddha fully experience the best of what cyclic existence has to offer, so that when he decides to renounce the world it is not because of misfortune or some inadequacy on his part, but rather a clear-eyed realization that even the best life situations are ultimately unsatisfactory and lead to continued rebirth and suffering. He must also prove that he is a sexual “stallion” who satisfies many women and who is the object of female desire.

Śuddhodana’s plan to entice his son to embrace his kingly heritage and the enjoyments it offered hit a snag when others began to question whether or not the boy fulfilled the ideal of a warrior kṣatriya. The prince’s apparent preference for the company of women led Daṇḍapāṇi, father of the beautiful Yaśodharā, to wonder if such a pampered boy was fit to rule a kingdom and subdue enemies in battle: “It is the custom of our family to give our daughters in marriage only to men skilled in the worldly arts, and your son has grown up in luxury in the palace. If he does not excel in the arts, does not know the rules of fencing or archery or boxing or wrestling, how could I give my daughter to him?” (Lalita-vistara: 100).

Siddhārtha rarely engaged in these activities, but training was unnecessary because his physical skills were so extraordinary that he could easily best all his contemporaries. Śuddhodana arranged a contest to which the most outstanding examples of kṣatriya manhood were invited, and Siddhārtha easily outshone all of them in “archery, fighting, boxing, cutting, stabbing, speed, and feats of strength, use of elephants, horses, chariots, bows, and spears, and argument” (Mahāvastu: II.73–74).

After witnessing this display, Daṇḍapāṇi happily assented to have his daughter marry Siddhārtha. The prince also had a harem of “beautiful, faultless, loving women, with eyes bright as jewels, with large breasts, resplendent white limbs, sparkling gems, firm and fine waists, soft, lovely, and black-colored hair, wearing bright red mantles and cloaks, bracelets of gems and necklaces of pearls, ornaments and rings on their toes, and anklets, and playing music” (Mahāvastu: II.147). Several narratives of this period also insert an interesting detail: he engaged in prodigious sexual activity, but he was not really interested. He knew that this was part of the narrative repertoire expected of an incipient buddha, and so he performed his part in the drama. After he had produced a son—which served to fully certify his masculine bona fides—he decided to leave his wife and harem, renounce his royal heritage, and pursue the life of a wandering ascetic seeking liberation. Although he wore coarse robes fashioned from cast-off rags, his body remained supremely attractive; the Deeds of the Buddha recounts that when women saw him in monastic garb, they were sexually attracted to him. They “looked up at him with restless eyes, like young deer, as their earrings, swinging back and forth, touched their faces, and their breasts heaved with uninterrupted sighs. [The Bodhisattva], bright as a golden mountain, captured the hearts of the best of women and captivated their ears, limbs, eyes and beings with his voice, touch, beauty and qualities respectively” (Buddha-carita: 69). Men were also struck by his physical perfection. When he visited the meditation master Ārāḍa Kālama, the sage exclaimed: “Look at the man who approaches! How beautiful he is!” His disciples responded: “We see him; he is indeed wonderful to behold!” (Lalitavistara: 174).

After several years of meditative training with various teachers, Siddhārtha succeeded in attaining advanced states of absorption, but they could not provide release from cyclic existence. He engaged in extreme ascetic practices, fasting for extended periods of time and reducing his sublime body to a state of emaciation, but this too proved incapable of providing the liberation he sought. So he set forth on his own to find the path to cessation, and after six years of meditative training he succeeded in attaining awakening in Bodhgaya. Following this experience, he began his ministry and taught others what he had realized. Many succeeded in becoming arhats, meaning they would attain nirvana after death.

In spite of his achievements, however, he could not overcome the limitations of physical existence. In his later years, he suffered from chronic back pain that was only relieved when he immersed himself in meditative trances. He told his cousin and attendant Ānanda that his body was like an old cart that is held together by cords, and he hinted that the time for his departure from physical existence was imminent. Even the body of a buddha is subject to change, as is true of all material things."

QUOTED EXERPTS posted for informational/educational purposes only.

- 677 reads