Submitted by BRENCIS CYRUS -... on

Submitted by BRENCIS CYRUS -... on

Derivative Images

In Magick Without Tears, Aleister Crowley observed a fundamental similarity between the “Secret Chiefs,” the invisible and inaccessible Masters to whom he professed obedience, and “Captain A. and Admiral B. of the Naval Intelligence Service.” Both, he noted, “keep in the dark for precisely the same reasons; and these qualities disappear instantaneously the moment They want to get hold of you.”1

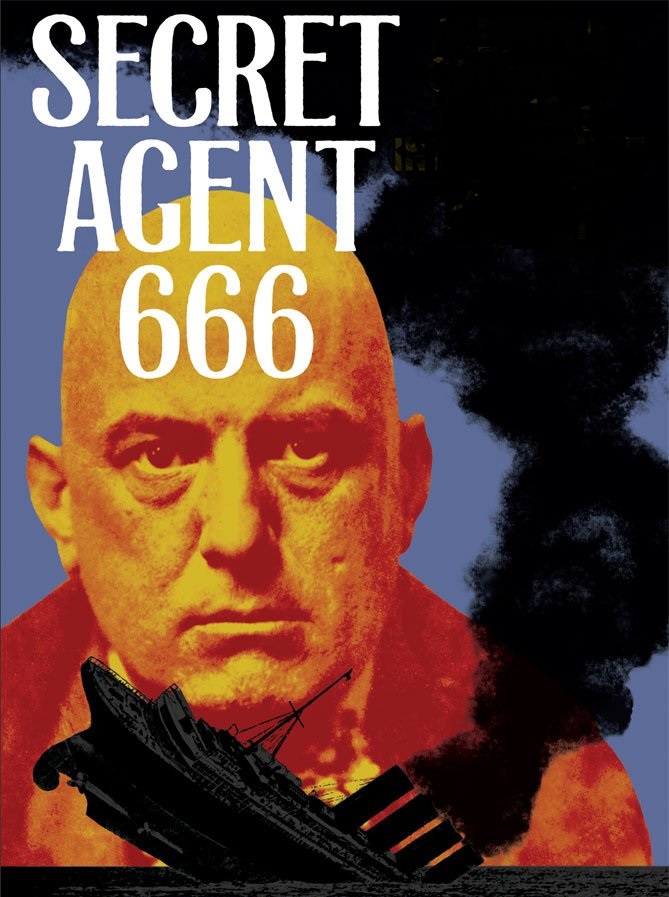

Crowley, arguably the most famous – or infamous – occultist of the last century, spoke from personal experience. Throughout his career, Mr. Crowley, aka “The Great Beast 666” and “the Wickedest Man in the World,” maintained some kind of connection with one or another aspect of British intelligence, most notably the Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence branch. His case is by no means exceptional. Many of his associates in the occult realm, among them Everard Feilding, Theodore Reuss, Hanns Heinz Ewers, and Maxwell Knight, also had links to one spy agency or another.

The inter-connection of occultism and espionage goes back at least to the Elizabethan intrigues of Dr. John Dee, and certainly is much older than that. For Crowley, Dr. Dee was a role-model in more ways than one. Occult orders and spy agencies do share much in common. Both are focused on the acquisition and safeguarding of specialised knowledge and embrace secrecy as a cardinal virtue. They are selective in recruitment and members are bound by oaths of silence and loyalty. They operate, so much as possible, outside public view or even public awareness. The pursuit of occult knowledge provides an excellent training ground for espionage and kindred intrigue, and vice versa. As Crowley’s literary creation Sir Anthony Bowling put it, “investigation of spiritualism makes a capital training ground for secret service work, one soon gets up to all the tricks.”2

What follows is a selective and inevitably brief survey of various persons who were involved in intelligence work and occult pursuits. The common denominator and main object of attention will be Crowley himself.

Crowley makes scattered allusions to intelligence work in his autobiographical writings but never offers any details. Generally, friend and foe have dismissed such claims as flights of fancy. However, far from inventing or exaggerating his clandestine exploits, he deliberately downplayed them or avoided mentioning them at all. A case in point is Crowley’s reference in his Confessions to his involvement in a 1899 conspiracy to foment a rebellion in Spain with the aim of restoring Don Carlos II to the country’s throne.3 Crowley teasingly offered to someday reveal the full and true story of the incident, but he never did.

There was much more involved in this affair than Crowley let on. The key figure in the British-based plot was Lord Betram Ashburnham. He was the leader of a small but determined cabal of British “Legitimists” whose aim was the replacement of Queen Victoria and her line with a restored Stuart dynasty. Ashburnham also reigned as grand master of a neo-Templar outfit dubbed the Order of St. Thomas of Acon. Another leading light among the Legitimists was S. L. MacGregor Mathers, who just happened to be the dominating figure of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (HOGD) and Crowley’s mentor and promoter in that esoteric organisation. The HOGD included a number of persons, among them William Butler Yeats, who were sympathetic to Irish nationalism and Celtic revivalism, ideas actively encouraged by the Legitimists.

Such sentiments inevitably aroused the curiosity of the guardians of the realm. The Spanish plot fizzled when someone, odds are Crowley, betrayed it from within. The Golden Dawn soon splintered as the result of internal rivalries in no small part exacerbated by Crowley’s disruptive antics. This episode represents one of his first forays into clandestine work and reveals the primary roles he played later on: infiltrator, informer and provocateur.

Crowley had good reason to stay mum about such things. First, there was the Official Secrets Act, a legal Sword of Damocles that threatened to come down on the head of anyone who revealed too much. Beyond that, Crowley’s services to the State bought him tolerance and even protection from the temporal powers-that-be. For all his outrageous behaviour, and despite public outcries that he be hanged or worse, the self-proclaimed Beast never ran into any serious legal difficulty in his homeland. Even his apparent treason during WWI was conveniently ignored.

I first stumbled upon Crowley’s intelligence angle while researching British espionage activities in WWI New York. More out of curiosity than anything else, I retrieved a small file from the records of the US Army’s Military Intelligence Division (MID). What immediately jumped out was a September 1918 report from the MID officer at West Point, New York. In this, he noted that as a result of his investigation of a strange Englishman who had been camping out on nearby Esopus Island, he discovered that the subject, one Aleister Crowley, “was an employee of the British Government on official business of which the British Consul, New York City has full cognizance.”4 Moreover, “the British Government was fully aware of the fact that Crowley was connected with… German propaganda and had received money for writing anti-British articles.” Clearly, the Beast’s later claims were not just flights of fancy.

The then British Consul in New York was Charles Clive Bayley, a career diplomat who had encountered Crowley in Russia a few years prior. The Beast’s 1913 visit to Moscow also seems to have included an intelligence dimension. However, the men at the New York Consulate most intimately involved with his clandestine activities were Captain (later Admiral) Guy R. Gaunt and Major Norman G. Thwaites. The first was the Australian-born naval attaché who ran British intelligence operations in New York early in the war. To all outward appearances, he was not the type to look kindly on Crowley or anything smacking of the occult. He cooperated with Crowley with evident reluctance and no doubt on the orders of higher-ups.

Thwaites worked for MI1c, then the operative cover for the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) later best known as MI6. As second-in-command to the station chief, Sir William Wiseman, Thwaites effectively ran the operation from 1917. Regarding things occultish, Thwaites was more open-minded. In his memoirs, Thwaites devotes an entire chapter to “Spiritism” and tells how in New York he used trance mediums and a Ouija board to expose a German plot.5 While he makes no overt mention of Crowley, it does not seem far-fetched to suppose that the Beast might have offered some sage advice.

A better example of the intelligence-occult connection among Crowley’s associates is the man who recruited him for secret work in 1914, his long-time friend, the Right Honourable F. H. Everard Feilding. Feilding was for years the secretary of London’s Society for Psychical Research (SPR) and had much experience in the investigation of mediums and paranormal phenomena. Of course, some in the SPR might argue that their pursuits were scientific, not “occult.” Still, Feilding’s interests definitely veered in the latter direction. In addition to being a longtime chum of Crowley, he was a member of the Beast’s very exclusive and very occult A.’.A.’. order.6

Soon after the outbreak of the war, Feilding nabbed a commission in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR), a common accommodation for intelligence work, and started out serving Admiral Reginald “Blinker” Hall and the Naval Intelligence Division (NID). By 1915, Feilding was in Athens attached to the East Mediterranean Special Intelligence Bureau, another branch of MI6, and spent the rest of the war in intelligence-related posts in Egypt and Syria. Sir Compton Mackenzie, who served with Feilding in Greece, later wrote of him that “his approach to the whole question of intelligence was that of one investigating a house alleged to be haunted.”7

Despite the great distance separating them, Crowley and Feilding kept in touch during the war. Indeed, Feilding received at least some of the Beast’s reports, intervened when Crowley ran into difficulty and overall acted as a kind of remote case officer.

Back in the summer of 1914, Crowley had hoped to land a commission like Feilding’s, but the latter, or his boss Admiral Hall, had something different in mind: an “unofficial” undercover mission in America. Crowley’s secret service in wartime America is a surprisingly complex story, so for now it must suffice that his single greatest accomplishment was the infiltration of a German propaganda ring headed by the German-American writer George Sylvester Viereck. From this vantage, Crowley spun a web of influence among German diplomats and spies and garnered the secrets of propaganda, sabotage and Berlin’s support to Irish and Indian nationalists. According to George Langelaan, a future British intelligence officer who later befriended Crowley in Paris, the Beast believed that he had played an indirect part in the sinking of the Lusitania by helping to convince gullible Germans that such brazen and bloodcurdling tactics would frighten the Yankees into curtailing trade with the Allies.8 It was no coincidence that back in London Admiral Hall hoped to push the Germans in the same direction.

The presumed source of Crowley’s influence with German schemers in the USA was his skill as a propagandist and his improbable profession of Irish nationalism (he not being in the least bit Irish). However, his reputation and connections as an occultist must have played some part as well. For instance, Viereck took at least an amateur interest in occultism and his penchant for orgiastic sex hints at an affinity for the sex-magic rites of the Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO), the esoteric body of which Crowley claimed to be the anointed head in America.

A “magickal” connection is even stronger in another German Crowley cultivated in New York, Hanns Heinz Ewers, who had at least some acquaintance with the OTO. Ewers was a serious student of the occult and a writer whose works reflected a fascination with the supernatural and sexual perversion.9 He also was a veteran agent of the German secret service and after coming to the US in 1914, Ewers undertook a series of secret missions to Spain and Mexico.

In the latter place, Ewers encountered another German mystic involved in clandestine affairs, Heinrich Arnold Krumm, better known as Dr. Arnoldo Krumm-Heller. Thanks in part to his masonic and Rosicrucian pedigrees, Krumm-Heller had finessed a position of influence near pro-German Mexican President Venustiano Carranza. In 1916, Krumm-Heller quietly passed through the New York area on his way back to Germany as a special emissary of Carranza. Unfortunately for him, someone tipped-off the British authorities, who pulled Krumm-Heller off the boat and sent him back to the States. Once again, that someone most likely was Crowley who could have pried the secret from a too trusting Ewers. In any case, someone kept Maj. Thwaites very well informed about Ewers’ contacts and activities.

It may be significant that Ewers, Viereck and others in the German secret apparatus were members of a quasi-masonic fraternal order called Schlaraffia. Ewers, in fact, was one of the organisation’s top officers. Outwardly, the society was dedicated to fellowship and good times, which did not rule out some members taking a deeper interest in occult matters. American and British intelligence pegged Schlaraffia as a “Secret German Propaganda Society” tasked with doing Berlin’s work “in a silent, secret way.”10

Crowley’s credibility among Germans like Ewers may have been enhanced by his association with a venerable member of both the German occult and intelligence milieus, Theodor Reuss. Reuss’ work for Berlin’s secret services dated back to the 1880s when he infiltrated the Socialist League in London. His chosen trade of journalist, as in so many other cases, provided a handy cover for intelligence-gathering of one sort or another. Reuss made London his home base for several years before 1914, where he probably acted as a talent-scout or recruiter for German intelligence.

Reuss also had a passion for joining or forming occult secret societies. His most notable association was with the above-mentioned Ordo Templi Orientis. Reuss became head of the Order around 1905, and in 1910 he recruited Aleister Crowley into its ranks. Two years later, he proclaimed the Beast head of the London branch. One can only wonder as to whether Crowley’s enlistment in the OTO included an overt or covert effort to draw him into Germany’s service. Might Crowley’s association with Reuss have been encouraged by someone in Britain’s secret service? Perhaps the OTO link was one reason that Feilding and Hall picked him for the New York job.

Crowley maintained contact with Reuss during the war. The latter, after a brief stint with German counter-intelligence (hunting English spies on the Dutch border), surfaced in neutral Switzerland where he schemed to entice expatriate radicals and other avant-garde types into the German net. His main such effort was the “Anational Lodge and Mystic Temple” which hosted a Congress at Monte Verita (a counter-culture haven in southern Switzerland) in the summer of 1917. Reuss featured Crowley’s Gnostic Mass in the ceremonies, but in New York Crowley quietly denounced Reuss’ efforts to the British and the Americans. For example, the Beast assured New York State Deputy Attorney General Alfred Becker that Reuss was an “out and out German” and a dangerous propagandist “whom he always thought might have some considerable official position in Germany.”11 He even hinted that Reuss had made a secret wartime visit to New York.

One more German of occult stripe with whose name Crowley’s ended-up linked in intelligence reports was Rudolf Steiner. He is best known as the founder and guiding light of Anthroposophy, the spiritual movement he founded after splitting with Annie Besant’s brand of Theosophy. Steiner’s wartime connection to the Beast is alleged in reports attached to Crowley’s MID file. Crowley and two other men, George Winslow Plummer, head of the Societas Rosicruciana in America, and a British mystic, the Rev. Holden Sampson, reportedly belonged to an “occult German order, the head of which is Dr. Rudolf Steiner in Berlin.”12 More ominously, they were supposed to be able to communicate with Steiner “without using any cable or telegraph system in public use.”

The precise “occult order” referred to was a mystery at the time and still is. Steiner was never head of the OTO, and the description does not fit Anthroposophy. The best that MID could determine was that it was some sort of Rosicrucian group. Of course, maybe it never existed at all, and Steiner’s followers could insist that their leader would never have sunk so low as to become involved in anything smacking of espionage.

However, Steiner devotees might be more bothered by a 1923 report titled “Rudolf Steiner and the Anthroposophical Society” also found in the American MID files. The document appears to be of British origin and is an addendum or response to previous MI6 communiqués about Steiner. There is no indication of the author’s identity, although he or she was well-versed in Steiner’s business and other affairs. It is not out of the question that Crowley was involved in its concoction one way or another. The gist of the report states:

“[Steiner’s] early training as a Jesuit, when he was probably initiated into occult secrets, of which this body makes a special study… and his friendship with Lenin in Switzerland in 1909; were all preparing him for a career of subtle, underground political intrigue, cleverly disguised under the cloak of religious illumination, which was to make him in future years such a dangerous power to Church and State.”13

Naturally, such accusations are not proof, but the document is evidence that Steiner and his ventures were matters of curiosity and suspicion to both American and British intelligence.

The above barely scratches the surface of Crowley’s 1914-19 escapades, but we need to look elsewhere to find further evidence of his and others’ involvement in espionage.

In the wake of WWI, the Beast established a small spiritual community/mystical school, dubbed the Abbey of Thelema, in an abandoned farmhouse near Cefalu on the northern coast of Sicily. In 1922, Italian authorities expelled him from the country, allegedly because of the unorthodox sexual practices at the Abbey. Oddly, they made no effort to shut down the place or give the boot to anyone save him. In 1926, an apparently deranged British woman named Violet Gibson tried to assassinate Italy’s new dictator, Benito Mussolini. The Fascist police discovered a link between the would-be assassin, Theosophist circles, and the above-mentioned Annie Besant.14 This spurred Italian authorities to take another look at papers seized from Crowley’s residence at Cefalu. Among them, a subsequent report noted, were documents from the “special espionage service” of the British Government and reports to same concerning conditions in Italy.15 The Beast seems to have been up to his old tricks.

Other materials linked Crowley to the British Consul in nearby Palermo. His name was Reginald Gambier MacBean and, as might be expected, he was a member of more than one occult organisation. First and foremost, he was a passionate follower of Besant and Theosophy. He held the allegiance as far back as 1917 which had once prompted an investigation by MI5. Shortly after Crowley set-up shop at Cefalu, MacBean assumed the title of Grand Master of a restored Memphis-Mizraim Masonic Lodge in Italy. According to Crowley, this esoteric branch of Freemasonry was aligned with the OTO. The question remains as to whether Theosophists, MacBean or Crowley had anything to do with the attempt on Mussolini, but there were more than enough tangled threads to make any sensible Fascist policeman suspicious.

Next, in 1928, Crowley’s name surfaced in correspondence between the India and Foreign Offices regarding the Russian artist, Theosophist and suspected Soviet asset, Nikolai Roerich. Arthur Vivian Burbury, who recently had spent three years as an MI6 man inside Britain’s Moscow Embassy advised that:

“As to possible sources about Roerich – his connection with Russia, Thibet… Theosophists… and various ‘secret’ organisations… leads me to think that information as to him might be obtained from an (undesirable) Englishman who has curiously intimate knowledge of all such things. His real name is Aleister Crowley.”16

Just how or when Burbury came to be acquainted with the Beast is another mystery, as are Crowley’s sources of information regarding Roerich. Nevertheless, it does demonstrate that however “undesirable” Crowley may have been in some circles, he still counted as a useful informant in others.

This much is certain: whatever his personal involvement, Roerich’s Central Asian expeditions during 1925-28 were backed and infiltrated by Soviet intelligence. The Kremlin’s chief agent-on-the-spot was Yakov Blumkin, an adventurous trouble-shooter who was himself alleged to be a student of the occult. Behind Blumkin stood the sinister chekist Gleb Bokii and his “parapsychologist” ally Alexander Barchenko, both men steeped in occult lore and practice.17

Around 1936-37, Crowley entered into a curious relationship with Maxwell Knight, head of the MI5 branch that handled “subversives” and their contacts with foreign agents. The basis of this relationship usually is presumed to be Knight’s keen interest in the occult, especially “black magic.” However, it seems probable that Knight also tapped the Beast’s vast reservoir of knowledge for more practical purposes. For example, in what arguably was Knight’s greatest counter-intelligence coup, the infiltration and breakup of a pro-Nazi ring during the early part of WWII, he employed at least one agent specifically chosen to exploit “interest in spiritualism, clairvoyance, astrology and anything to do with the occult.”18

In truth, Knight’s interest in Crowley began years earlier. His onetime agent Joan Miller recalled a rumour around MI5 that Knight’s former wife had perished “in some sort of occult misadventure in which the notorious Aleister Crowley was involved.”19 The tale is apocryphal; the unfortunate Mrs. Knight died from an accidental (?) drug overdose. But that does not rule out she or her husband having had previous knowledge of the Beast. In the early ‘20s, Maxwell was the “director of intelligence” for the British Fascisti, and in that capacity he worked very closely with a certain George Makgill. Makgill was obsessed with uncovering nefarious cults and conspiracies, one of which he was convinced was headed by the horrid Mr. Crowley.

Last but no means least, there is the vague if persistent tale that Crowley was involved in the affair of Rudolf Hess, the high-ranking Nazi who flew to Scotland in early 1941 on an ill-fated peace mission. The basic story comes from Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, who at the time was an officer in British Naval Intelligence and right-hand-man to NID’s chief, Admiral John Godfrey. Fleming later confessed that one of his unfulfilled wartime schemes was to have Hess, a man strongly influenced by occult beliefs, interviewed by Aleister Crowley.20 According to Fleming, the Beast was more than willing, but the one who stepped forward to kill the idea was none other than Maxwell Knight.

Interestingly, immediately after the war’s outbreak, Crowley had received a note from Fleming’s boss, Admiral Godfrey, extending his greetings and summoning Crowley to an interview at the NID offices.21 Godfrey directed the Beast to a Commander C. J. M. Lang. A veteran intelligence officer, Lang was then connected to the NID section dealing with the interrogation of POWs. Yet another story, though no more, claims that Crowley ultimately did encounter Hess at a hush-hush MI5 interrogation facility known as Camp 020 or Latchmere House.22 If so, did Max Knight quash Fleming’s plan because he had his own plans for Hess and Mr. Crowley?

In conclusion, the preceding by no means exhausts the connections between Crowley, intelligence and the wider occult realm. The names of George Gurdjieff, Jack Parsons, Nikola Tesla and even Crowley’s “widow,” Patricia Deirdre Doherty, could be invoked along with many others.

Hopefully, this brief article offers a glimpse into what was – and no doubt still is – a significant cross-pollination between the two spheres, a connection about which much remains to be learned.

Dr. Richard B. Spence - https://www.newdawnmagazine.com/articles/the-magus-was-a-spy-aleister-crowley-and-the-curious-connections-between-intelligence-and-the-occult

© Copyright New Dawn Magazine, www.newdawnmagazine.com. Permission granted to freely distribute this article for non-commercial purposes if unedited and copied in full, including this notice.

© Copyright New Dawn Magazine, www.newdawnmagazine.com. Permission to re-send, post and place on web sites for non-commercial purposes, and if shown only in its entirety with no changes or additions. This notice must accompany all re-posting.

Footnotes:

- A. Crowley, Magick Without Tears. New York: Ordo Templi Orientis, 1954, pp.61-62, or www.hermetic.com/crowley/mwt/mwt_09.html.

- Ibid., Moonchild. London: Mandrake Press, 1929, 308, or www.hermetic.com/crowley/moonchild/mc22.html. “Sir Anthony Bowling” was Crowley’s alias for Everard Feilding.

- Ibid., The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autohagiography. London: Mandrake Press, 1930, p.120.

- US National Archives, Military Intelligence Division (MID), General Summary, Intelligence Officer, West Point, N.Y., 23 Sept. 1918, p.4.

- Thwaites, Velvet and Vinegar, London: Grayson & Grayson, 1932, pp.233-240.

- Commonly assumed to stand for Ordo Astrum Argentum or Argenteum Astrum (“Silver Star”) though the true meaning is known only to initiates.

- Compton Mackenzie, Greek Memories. London: Chatto & Windus, 1939, pp.29-34.

- George Langelaan, “L’agent secret, fauter de paix,” Janus (#2, Sept. 1964), pp.49-51.

- On Ewers’ career see Wilfried Kugel, Der Unverantwortliche: Das Leben des Hanns Heinz Ewers. Duesseldorf: Grupello Verlag, 2001.

- MID, 10516-474/31, “In Re: Hans [sic] Heinz Ewers,” 24 June 1918.

- US National Archives, Department of Justice, Bureau of Investigation, Old German Files, Case # 365,985, Report of Agent O’Donnell, 30 July 1919.

- MID, 9140-808, Office of Naval Intelligence, “German Suspects,” 10 July 1917, etc.

- MID 9140-808, 21 April 1923.

- These events are presented in novelised form in Claudio Mauri’s La Catena Invisibile: Il giallo del fascismo magico. Milan: Mursia, 2005.

- Marco Pasi, Aleister Crowley e la tentazione della politica. Milan: FrancoAngeli, 1999, pp.175-176, pp.196-199.

- Phil Tomaselli to author, 18 Dec. 2003, extracted from July 1926 correspondence between the India Office and the Foreign Office Library.

- On these people and connections see Aleksandr Andreev, Okkul’tist strany sovetov. Moscow: Eksmo, 2004, Oleg Shishkin, Bitva za Gimalei. Moscow: Eksmo, 2003, and Markus Osterrieder, “From Synarchy to Shambhala: The Role of Political Occultism and Social Messianism in the Activities of Nicholas Roerich,” paper presented at the international conference on “The Occult in 20th Century Russia,” Berlin, March 2007.

- Bryan Clough, State Secrets: The Kent-Wolkoff Affair. Hove: Hideaway Pub., 2005, p.31.

- Joan Miller, One Girl’s War: Personal Experiences in MI5’s Most Secret Section. Dingle, Eire: Brandon Books, 1986, p.45.

- John Pearson, The Life of Ian Fleming. London: Companion Books, 1966, pp.117-118.

- Martin Booth, A Magick Life: A Biography of Aleister Crowley. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2000, p.395.

- P. R. Koenig, “Crowley Met Rudolf Hess,” www.groups.yahoo.com/thelema93-1/messsage/2733, 31 August 2000.

- 964 reads