Submitted by Holyman Preter on

Submitted by Holyman Preter on

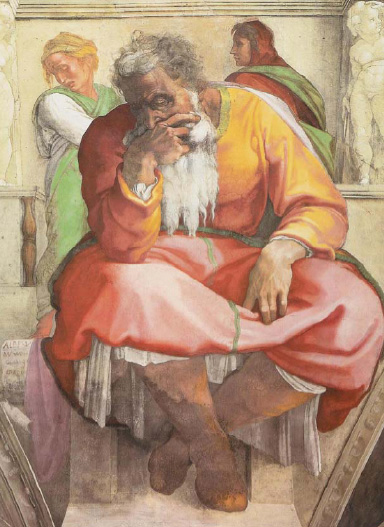

By Michelangelo - The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202.,

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=155641

While the internet was supposed to produce a bevy of incisive, free-wheeling discourse, it has instead begotten a never-ending series of almost invariably predictable debates. Spend enough time online, and you can begin to predict with striking prescience exactly how a particular discussion will unfold: if someone submits input A, they will get output B.

Case in point: whenever someone says: “Young people today are (insert negative trait here),” someone else will almost assuredly counter the contention by busting out this quote from Socrates:

“The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. Children are now tyrants, not the servants of their households. They no longer rise when elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.”

Ah-ha! Perfect proof that older people have always complained about youngsters and young people have always misbehaved! Things haven’t changed at all!

This particular internet debate “output” has always made me shake my head for a few reasons:

1. Alas, Socrates never actually said that. The quote in fact originated around the turn of the 20th century.

Even though the quote is completely spurious, the part of the point it is often marshaled to make is still true: people have always complained about young people. One can find somewhat similar sentiments in the writings of other ancient cultures, and I’ve read plenty of complaints about “young people today” in books from a couple centuries back.

2. However, while it is true that people have griped about the improprieties of youth since time immemorial, such quotes still do not prove the other part of the argument: that young people today aren’t any worse than they used to be. Here’s why:

Let’s say that on the hottest day in the summer of 400 BC it’s 90 degrees, and someone writes in their journal, “Boy it’s hot outside!” Then on a 95-degree day in 1700, someone writes down the exact same thought. Finally, on a record-breaking day in 2014, when the temperature soars to 100 degrees, someone declares, “Man, it’s hotter than ever!” If someone else were to counter this statement by saying, “Meh, look at these old journal entries — people have always complained about the heat,” that would not in fact prove that temperatures hadn’t gotten hotter over time.

Here’s another example more relevant to the original supposition: During the Jazz Age, dances like the Charleston and Lindy Hop were considered sexual and indecent. Even the Foxtrot, which now epitomizes class, came in for criticism for the amount of physical touching between partners. If someone today were to drop in on a high school prom and witness students bumping and grinding, they might deride such “dancing” as highly sexual. The fact that people once had the very same complaints about dances in the Jazz Age wouldn’t prove that today’s dances haven’t become more sexual. On the contrary, they demonstrably have.

3. Even if it isn’t true that young people have gotten any worse over time, criticizing them still serves a purpose — as does criticism of all ages of people, and society at large. Cultural critiques – issued in the form of the jeremiad – are actually what contribute to keeping the accusations untrue.

Allow me to explain.

What Is a Jeremiad?

A jeremiad is a form of rhetoric in which the speaker/writer sharply laments a society’s sins and shortcomings, and predicts that his people’s offenses will lead to their demise and collapse. It is a stern, ominous, sustained invective against the immorality of one’s culture – an attempt to reveal the sins everyone else is willfully ignoring.

As you may have guessed, the word comes from the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah, who believed he was called by God to prophesy that Israel would be destroyed in consequence for their failure to keep the Mosaic covenant.

While the jeremiad has its roots in religious preaching, over time it has expanded to encompass a variety of ethos and mediums. Jeremiads can take the form of poems, songs, novels, speeches, articles, and even movies. They can concern both spiritual and secular matters, and while we often think of them as conservative in bent, they can be progressive as well.

It’s also important to point out that while we typically associate this form of rhetoric with doom and gloom, jeremiads always have a layer of optimism as well; they are given in the hope that in showing the listener/reader how far they have fallen from the ideal, they will be motivated to strive for improvement. They look forward to a brighter day — a new golden age. Jeremiah himself, for example, did not only foretell Israel’s destruction, but prophesied that his people would eventually rise from the rubble to become even stronger than before.

The jeremiad has had a particularly significant place in American culture. Americans have long thought of themselves as a special people with a special mission, due to the way in which the country was created through a series of idealistic founding events. The country’s birth was woven with promises and principles that we have sought to recapture and live more perfectly ever since.

The Puritans were the first to conceive of the nation as a “city on the hill,” and jeremiad-type warnings about living up to this model accompanied such rhetoric from the very start. In the same sermon in which John Winthrop exhorted his fellow settlers to be a light to the world, he predicted that “if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken, and so cause Him to withdraw His present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world.”

When a new nation was officially created a century later, another founding took place, and the ideal for Americans to live up to became a kind of civil religion. The principles and promises of democracy – and the documents upon which they were recorded — took on a sacred weight. In the centuries since, cultural reformers and critics have frequently evoked the Constitution, and the bloody sacrifices made over the decades to protect it, to point out where we have fallen short, and to motivate citizens to close the gap between the current reality and what they argue was the founders’ original intent.

For this reason, the jeremiad has a long history as part of African-American culture. Reformers like Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King Jr. used it to illuminate the ways in which the Constitution’s guarantees of freedom and equality remained unfulfilled for blacks. They argued that things like the Civil War and the civic turbulence of the 1960s were a divine punishment for the sins of slavery and discrimination, and would not cease until Americans “repented” and made things right.

Throughout American history (and in countries around the world), the jeremiad has been employed by those on the left and on the right — ministers and labor union leaders, gun rights defenders and civil rights activists, feminists and masculinists — to decry those areas of culture in which they believe their people have fallen short. The jeremiad remains alive and well today, and while we may be tempted to turn away from them, we would do well to actively seek them out instead.

The Temptations to Tune Out

Jeremiads have never been popular with the masses in any age. Nobody likes to hear that they’re decadent and depraved; we’d much rather get a pat on the back and a hearty “well done!”

Yet while jeremiad-spewing prophets and reformers never achieve widespread acceptance, they do often gain a sizable following. There are always individuals who see truth in what these reformers say and embrace the chance to turn from their morally-bankrupt ways.

Yet I think there are several obstacles particular to our modern age of which we should be aware that may inhibit even these humble, open-minded types from giving jeremiads a fair hearing:

Our over-inflated sense of self-worth. While people have never enjoyed hearing that they’re not as awesome and upstanding as they think they are, there has never before been such a gap between the average man’s self-perception and reality. Thus jeremiads have never before been so likely to be greeted with disbelief and antagonism. We’re told that we’re special from an early age, and that no one has the “right” to say we’re not good enough. “We are good enough, and gosh darn it people like us! Anyone who thinks otherwise can go to hell.”

Our choice-abundant society. There was a time where people could quite literally get up on a soapbox and make themselves heard. There wasn’t an awful lot going on, so if the rabble-rouser was interesting enough (even if he made people furious, maybe especially if he made them furious), he could amass a large audience. Today the internet has completely democratized the ability to potentially get one’s rantings out to the masses, but at the same time, it has created millions of other options competing for people’s attention. With so many choices for listening or surfing, people are liable to tune out the person who convicts them in their weakness, and latch on to those who offer a more flattering message.

Our consumer-driven culture. The number of options vying for people’s time and money has led to every institution taking a consumer-driven approach and catering to, instead of challenging, people’s preferences. Even formerly hallowed institutions like colleges and churches have succumbed to this trend. If a professor says anything too inflammatory, students will protest his class. If a minister calls his congregants to repentance, they’ll just head to the megachurch down the road where the friendly pastor offers positive, affirming, Joel Osteen-esque sermons that make them feel good about themselves and about life. Jonathan Edwards could get away with telling his audience they were “sinners in the hands of an angry god” – there weren’t too many other options for church meetings in Northampton, Mass. Today’s spiritual seekers can shop around until they find a minister with a perspective that exactly aligns with their own.

One can even trace the disappearance of the jeremiad through hip-hop music. In its early days, hip-hop artists wrote songs that were sharply critical of culture and politics. But along the way they figured out that a mainstream audience didn’t want their music to engage big issues, but to help them forget their issues. And so the music went from “Fight the Power” to “Whistle While You Twurk.”

Our short attention spans. Even if a modern person can put aside their umbrage at being criticized and begin to engage a jeremiad, they are not likely to make their way all the way through it. In our TLDR culture, people actually celebrate their short attention spans, claiming that anything worthwhile can be condensed into something short and pithy. Were they to have lived in ancient times, they would have said, “Dude, Socrates, too much filler — can you give me the Cliff Notes version already?”

Our lack of a shared ideal. Jeremiads evoke a sacred founding or creation event – the moment in time when a people made a certain covenant or set forth a set of common principles. Jeremiads challenge people to live up to their own history. But today, there is little agreement on what the ideal way of living should be, and many feel like they should not be constrained by standards that were erected in a hazy past.

Our worship of the cool. We moderns like nothing more than being cool. Sophisticated. In the know. And jeremiads are anything but. Cool people laugh at anyone who preaches doom and gloom – who even hints that our culture might be weak and decadent.

The Daily Show, for example, is often a televised deconstruction of jeremiad-like discourse. A clip of someone with a supposedly ignorant/bigoted opinion is played and then carved up for yuks. I’m actually a regular watcher of the show, and usually enjoy it (which I’m telling you so you know I’m cool), and this comedic deconstruction can sometimes be quite incisive and serve an enlightening purpose. But it does represent well our culture’s current stance towards jeremiad-type rhetoric.

I say jeremiad-type, because in fact, what is usually skewered on the show is not the real deal, but modernity’s rhetorical medium of choice — the pseudo-jeremiad.

The Proliferation of Pseudo-Jeremiads

We all know the pseudo-jeremiad well. It dominates many blogs, 24/7 news channels, and talk radio programs.

The pseudo-jeremiad has many of the trappings of the traditional jeremiad – it angrily laments where our culture has gone astray, and predicts society’s demise if such trends continue. But it departs from the classical model in one key way: it blames other people, rather than those in the audience, for society’s problems.

A jeremiad is a challenge to one’s own people. It should convict the speaker’s or reader’s core audience as to their sins and shortcomings. It should shame them. If it doesn’t offend some of them or make some of them angry, it hasn’t served its purpose.

Pseudo-jeremiads, in contrast, flatter the speaker’s or writer’s audience. “We’re doing awesome, we’re in the know, but those other people are immoral ignoramuses who are ruining the world.”

Thus a liberal who tells his liberal audience that conservatives are a bunch of backwards bigots is not issuing a jeremiad; likewise a conservative that says that all liberals are effeminate pinheads isn’t offering a jeremiad either. But if a conservative or liberal went after his own political party for its excesses, that would be a jeremiad in the classical mold.

Pseudo-jeremiads aren’t necessarily a bad thing. Some can still be sharp and incisive, showing people the support behind their already-held beliefs, inspiring them to continue living those beliefs, and helping them see their beliefs in a new light. But one’s information “diet” should also be supplemented with pointed, piercing criticisms that challenge those beliefs entirely.

Why Should Every Man Engage with Hard-Hitting Jeremiads?

“Therefore, since the world has still

Much good, but much less good than ill,

And while the sun and moon endure

Luck’s a chance, but trouble’s sure,

I’d face it as a wise man would,

And train for ill and not for good.” –A.E. Housman

The general knock against jeremiads is that they’re nothing more than angry screeds that are often given by cranky, closed-minded old-timers who fear change, are overly anxious about “kids today,” and long for a time that never was. Jeremiads are frequently dismissed as gloomy diatribes that lack nuance because they only concentrate on the negatives of something, and miss the bigger picture by ignoring evidence that belie their claims.

Indeed, the truth does usually lie between the extremes on both sides of the spectrum, but, I would contend that jeremiads play a vital role in creating this between.

In any given society, you always have three groups of people — two on the extreme ends, and then the moderate middle. At one end you have the “eat, drink, and be merry” types who spurn any notion of society’s slide into decadence, and in fact embrace it. Then there is the crowd that spends all their time wringing its hands about rampant immorality and assuredly believes we are on the cusp of utter collapse.

In the middle you have the majority of folks, who worry about signs of cultural decay, but don’t think we’re on the wrong track with everything. Yet the existence of this moderate crowd is in fact contingent on their willingness to occasionally engage with jeremiads.

Actively seeking out arguments for moral indulgence isn’t necessary; every man, woman, and child has a built-in penchant to follow their natural desires, and we’re bombarded 24/7 by media images selling the desirability of giving in to our base appetites (restraint isn’t profitable for corporations). But if we wish to avoid sliding into moral decadence and mental decay, we do have to intentionally seek out rhetoric that offers the very opposite message. We need penetrating analyses that arouse us out of apathy and snap us out of our drift towards the path of least resistance. Even if we don’t end up agreeing with many of the contentions contained in a particular jeremiad, there is usually a kernel of truth to it that pricks the heart and convicts us in our weaknesses. Even when they initially offend us, or make us angry, they still, if we are humble, almost invariably lead to reflection on where we can improve. A sense of insecurity can truly be a positive thing, and questioning if we’ve gotten too comfortable individually and as a culture is absolutely vital to the health of both enterprises.

One can think of it like two separate pipes leading into the same faucet. Through one pipe flow the inclinations of the “natural man” that lead us to the path of least resistance; through the other comes the jeremiad that tells us we have fallen short and need to shape up. These two streams mix, and what emerges from the faucet is the Golden Mean.

Ultimately then, while the jeremiad’s lamentation of wholesale decay is rarely completely true, it is ironically this form of rhetoric’s existence that keeps it from being entirely true. Mark Twain said that “every civilization carries the seeds of its own destruction”; jeremiads are the caustic, but necessary herbicide that keeps those seeds from ever bearing fruit.

- 509 reads