Submitted by Prof. Cosmo on

Submitted by Prof. Cosmo on

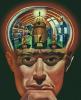

Speaking of hyperminds....

I want to distinguish two ways of being a group mind, since I know you care immensely about the cognitive architecture of group minds I'm a dork. My thought is that the philosophical issues of group consciousness and personal identity play out differently in the two types of case.

Synchronic:

Examples: Star Trek's Borg (mostly), Ann Leckie's ancillaries, highly interconnected nations (according to me), Vernor Vinge's tines.

Synchronic group minds are probably the default conception. A bunch of independent, or semi-independent, or independent-enough entities remain in constant or constant-enough communication with each other. Their communication is sufficiently rich or sufficiently well structured that it gives rise to group-level mental states in the whole. In the most interesting case, the individual entities are distinct enough to have rich mental lives but also the group is well enough coordinated that it also, simultaneously, has a distinctive, rich mental life above and beyond that of its members.

Diachronic:

Examples: David Brin's Kiln People, Linda Nagata's ghosts, Benjamin Kinney's forks.

In a diachronic group mind, communication is relatively rare but high bandwidth and transformative. Post-communication, the individuals inherit mental states from the others. In the most interesting case, the inheritance process is very different from just listening credulously to someone's testimony; rather it's more like a direct transfer of memories, plans, and opinions, maybe even values or personality. Imagine "forking" into three versions of yourself, going your separate ways for the day, and then at the end of the day merging back into a single individual, integrating the memories and plans of each, and averaging any general changes in value, opinion, or personality. Tomorrow and every day thereafter, you will fork and merge in the same way.

Tradeoffs Between Group-Level and Individual-Level Personhood and Autonomy:

As I have described it here, delay between information transfer episodes is the fundamental difference between these types of group minds: whether the minds are in constant or constant-enough communication, or whether instead they communicate only at long intervals. Obviously, temporal distance admits of degree, but this difference in degree creates structural pressures. If communication is infrequent, its effects have to be radical if it is to give rise to an entity sufficiently integrated to be worth calling a "group mind". If every day group of friends meets to exchange information and plan the next day's activities, in the ordinary way people sometimes do this, I suppose that in some weak sense they have formed a group mind. But they haven't done so in the radical science-fictional sense I'm imagining. For example, if there were five friends who did this, there would still be exactly five persons -- entities with serious rights whose destruction would we worth calling murder. For the emergence of something more metaphysically and morally interesting, the exchange has to be radical enough to challenge the boundaries of personal identity.

Conversely, if communication is constant and its effects are radical, it's not clear that we have a group of individuals in any interesting sense: We might just have a single non-group entity that happens to be spatially scattered.

In other words, to be a philosophically-interesting group entity there must be some sort of interestingly autonomous mentality both at the individual level and at the group level. Massive transformative communication (as in diachronic merging of memories and values) radically reduces autonomy: If communication is both massively transformative and very frequent, there's no chance for interesting person-like autonomy at the individual level. If communication is neither massively transformative nor very frequent, there's no chance for interesting person-like autonomy at the group level.

Consciousness:

Our intuitive judgments about group-level consciousness are probably pretty crappy (as I've argued here and here). But our general theories about consciousness as they apply to the group level are probably even crappier (as I've argued here and here). At the same time, whether the group as a whole has a stream of conscious experience over and above the consciousness of its individual members seems like a very important question if we're interested in its mentality and whether it deserves moral status as a person. So we're kind of stuck. We'll have to guess.

Plausibly, in the diachronic case there is no stream of consciousness beyond that of the merging individuals. When there's one body at night, there's one stream of consciousness (at most, if it's dreaming). When there are three bodies off doing their thing, there are three streams of consciousness. We might be able to create some problematic boundary cases during the merge, but maybe that's marginal enough to dismiss with a bit of hand waving.

The synchronic case is, I think, more conceptually challenging with respect to consciousness. If we allow that minimally interactive groups do not give rise to group level consciousness and we also allow that a fully informationally integrated but spatially distributed entity does give rise to consciousness, it seems that we can create a slippery slope from one case to the other by adding more integration and communication (for example here). At some point, if there is enough coherent behavior, self-representation, and information exchange at the group level, most standard functionalist views of consciousness (unless they accept an anti-nesting principle) should allow that each individual member of the group would have a stream of experience and also that there would be a further, different stream of experience at the group level. But it's a tricky question how much integration and information exchange, and with what kind of structural properties, is necessary for group-level consciousness to arise.

Personhood:

One interesting issue that arises is the extent to which an individual's beliefs about what counts as "self-interest" and "death" define the boundaries of their personhood. Consider a diachronic case: You are walking back home after your day out and about town, with a wallet full of money and interesting new information about a job opportunity tomorrow, and you are about to merge back together with the two other entities you forked off from this morning. Is this death? Are "you" going to be gone after the merge, your memories absorbed into some entity who is not you (but who you might care about even more than you care about yourself)? In walking back, are you magnanimously sacrificing your life to give your money and information to the entity who will exist tomorrow? Would it be more in your self-interest to run away and blow your wad on something fun for this current body? Or, instead, will it still be "you" tomorrow, post-merge, with that information and that money? To some extent, in unclear cases of this sort, I think it might depend on how you think and feel about it: It's to some extent up to you whether to conceptualize the merging together as death or not.

A parallel issue might arise with synchronic groups, though my hunch is that it would play out differently. Synchronic groups, as I'm imagining them, don't have identity-threatening splits and merges. The individual members of synchronic groups would seem to have the same types of rights that otherwise similar individuals who aren't members of synchronic group minds would have -- rights depending on (for example, but it's not this simple) their capacity to suffer and think and choose as individuals. They might choose, as individuals, to view the group welfare as much more important than their own welfare (as a soldier might choose to die for sake of country); but unless there's some real loss of autonomy or consciousness, this doesn't threaten their status as persons or redefine the boundaries of what counts as death.

Eric Schwitzgebel

http://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2018/07/two-ways-of-being-group-mind-synchronic.html

- 579 reads