Submitted by Rabilis the Alc... on

Submitted by Rabilis the Alc... on

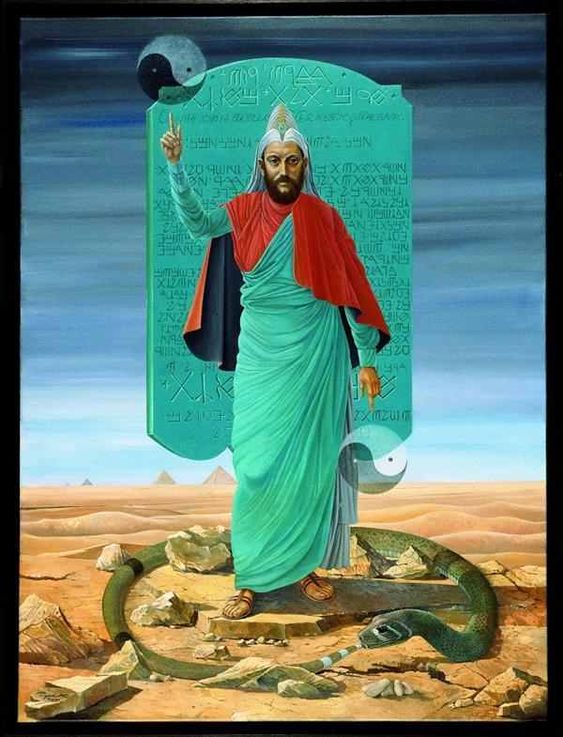

The Seven Principles of Hermes Hermes Trismegistus The Emerald Tablet via http://illuminatizeitgeist.tumblr.com

In the 7th century the Arabs started a process of territorial expansion that quickly brought them empire and influence ranging from India to Andalusia. Fruitful contacts with ancient cultural traditions were a natural consequence of this territorial expansion, and Arabic culture proved ready to absorb and reinterpret much of the technical and theoretical innovations of previous civilizations. This was certainly the case with respect to alchemy, which had been practiced and studied in ancient Greece and Hellenistic Egypt. The Arabs arrived in Egypt to find a substantial alchemical tradition; early written documents testify that Egyptian alchemists had developed advanced practical knowledge in the fields of pharmacology and metal, stone, and glass working. The first translations of alchemical treatises from Greek and Coptic sources into Arabic were reportedly commissioned by Khalid ibn Yazid, who died around the beginning of the 8th century. By the second part of that century Arabic knowledge of alchemy was already far enough advanced to produce the Corpus Jabirianum— an impressively large body of alchemical works attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan. The Corpus, together with the alchemical works of Al-Razi, marks the creative peak of Arabic alchemy.

As is typical in the chain of transmission of ancient knowledge, the origins of alchemy are steeped in legend, and the links of this chain are either mythical or real authorities in the fields of ancient science and philosophy. The doctrines on which Arabic alchemy relied derived from the multicultural milieu of Hellenistic Egypt and included a mixture of local, Hebrew, Christian, Gnostic, ancient Greek, Indian, and Mesopotamian influences.

The presence of the Arabic definite article al in alchemy is a clear indication of the Arabic roots of the word. Hypotheses about the etymology of the Arabic term al-kimiya hint at the possible sources for early alchemical knowledge in the Arab world. One of the most plausible hypotheses traces the origin of the word back to the Egyptian word kam-it or kem-it, which indicated the color black and, by extension, the land of Egypt, known as the Black Land. Another hypothesis links kimiya to a Syriac transliteration of the Greek word khumeia or khemeia, meaning the art of melting metals and of producing alloys.

A third interesting but far-fetched etymology suggests that the word al-kimiya derives from the Hebrew kim Yah, meaning “divine science.” The idea of a connection between the origins of alchemical knowledge and the Jews was widespread among medieval Arabic alchemists, who saw in this etymology a possible confirmation of their belief. These alchemists tended to attribute the mythical origins of alchemy alternately to the angels who rose against God, to the patriarch Enoch, to King Solomon, or to other biblical characters who taught humankind the secrets of minerals and metals. This interpretive strategy dignified the origins of alchemy and attributed alchemical books pseudepigraphically to authorities of the past, providing a safe mechanism for spreading alchemical knowledge, which could otherwise be persecuted for its proximity to magic.

In contrast with the modern term alchemy, the word al-kimiya lacks abstract meaning. Rather than designating the complex of practical and theoretical knowledge we now refer to as alchemy, it was used to describe the substance through which base metals could be transmuted into noble ones. In Arabic alchemical books al-kimiya tended to be a synonym of al-iksir (elixir) and was frequently used with the more general meaning of a “medium for obtaining something.” Expressions like kimiya al-sa‘ada (the way of obtaining happiness), kimiya al-ghana (the way of obtaining richness), and kimiya alqulub (the way of touching hearts) testify to the broad meaning of this word. What we now call alchemy was called by other words: san‘at al-kimiya or san‘at al-iksir (the art or production of the elixir), ‘ilm al-sina‘a (the knowledge of the art or production), al-hikma (the wisdom), al-‘amal al-a‘zam (the great work), or simply al-sana‘a. Arabic alchemists called themselves kimawi, kimi, kimiya’i, san‘awi, or iksiri.

The contribution of Arabic alchemists to the history of alchemy is profound. They excelled in the field of practical laboratory experience and offered the first descriptions of some of the substances still used in modern chemistry. Muriatic (hydrochloric) acid, sulfuric acid, and nitric acid are discoveries of Arabic alchemists, as are soda (al-natrun) and potassium (al-qali). The words used in Arabic alchemical books have left a deep mark on the language of chemistry: besides the word alchemy itself, we see Arabic influence in alcohol (al-kohl), elixir (al-iksir), and alembic (al-inbiq). Moreover, Arabic alchemists perfected the process of distillation, equipping their distilling apparatuses with thermometers in order to better regulate the heating during alchemical operations. Finally, the discovery of the solvent later known as aqua regia—a mixture of nitric and muriatic acids—is reported to be one of their most important contributions to later alchemy and chemistry.

Arabic books on alchemy stimulated theoretical reflections on the power and the limits of humans to change matter. Moreover, we have the Arabic alchemical tradition to thank for transmitting the legacy of the ancient and Hellenistic worlds to the Latin West.

Theoretical Assumptions

The alchemical authorities most often quoted as sources in Arabic alchemical texts were Greek philosophers, such as Pythagoras, Archelaus, Socrates, and Plato. During the Middle Ages, Aristotle himself was considered the authentic author of the fourth book of Meteorologica, which deals extensively with the physical interactions of earthly phenomena, and of one letter on alchemy addressed to his pupil Alexander the Great. Arabic language sources also quoted Hermes, the supposed repository of the knowledge God gave to man before the Deluge and to whom legend attributes the famous Tabula smaragdina (Emerald Tablet); Agathodaimon; Ostanes, the Persian magician; Mary the Jewess (probably 3rd century), for whom the bain marie (akin to a double boiler) is named; and Zosimus of Panopolis (3rd–4th centuries), believed to be the author of an alchemical encyclopedia in 28 books. Indeed, Zosimus is said to have introduced religious and mystical elements into the alchemical discourse: his books meld Egyptian magic, Greek philosophy, Neoplatonism, Babylonian astrology, Christian theology, pagan mythology, and doctrines of Hebrew origin in a highly symbolic writing full of allusions to the interior transformations of the alchemist’s soul.

Arabic alchemists largely worked from an Aristotelian theory of the formation of matter in which the four elementary qualities (heat, coldness, dryness, and moisture) generate first-degree compounds (hot, cold, dry, and moist), which, in turn, combine in pairs, acquire matter, and generate the four elements: hot + dry + matter = fire; hot + moist + matter = air; cold + moist + matter = water; cold + dry + matter = earth. Everything on earth consists of varying proportions of these four elements. A particularly clear explanation of how alchemists made sense of Aristotelian theory can be found in the pseudo-Avicennian treatise De Anima in arte alchimiae (Basel, 1572), an alchemical work probably of Arabic origins that survives only in Latin translation. According to this treatise, every existing body is a compound of the four elements: if a body is defined as cold and dry, this means that the qualities of coldness and dryness predominate, while heat and moisture occur in minor proportions and thus remain concealed. An external cause—either natural or artificial—could generate a change in the structure of the body, rebalancing the natural proportion of its external and internal qualities, thereby changing its appearance. The alchemist in his laboratory seeks to artificially overturn the balance of qualities in the body he is trying to transmute by adding or removing heat, coldness, dryness, or moisture.

Arabic natural philosophy similarly accepted the classical theory of the formation of minerals in mines. This explanation held that two different movements take place in the depths of caves as the caverns are heated by the sun: particles of water (cold and moist) rise to the surface and generate vapors (bukhar) when they make contact with air (hot and moist); particles of earth (cold and dry), however, rise to the surface and generate fumes (duhan). The meeting of vapors and fumes creates quicksilver, if the vapors predominate, or sulfur, if the fumes predominate. Gold is generated when quicksilver and sulfur are pure and in a balanced proportion, and the soil and astral conditions are positive. Imperfections in any of these conditions create metals of progressively lesser value. An impressive description of the formation of metals in caves can be read in Epistle 19, on mineralogy, of the Rasa’il Ikhwan al-safa’ (Epistles of the Brethrens of Purity), a 10th-century encyclopedia of science, religion, and ethics attributed to a group of philosophers influenced by Neoplatonism and Pythagorism.

The alchemist’s goal, to be achieved through study and practical expertise in the laboratory, was to reproduce these natural processes in a shorter period or to interfere somehow with the natural processes to produce “natural accidents.” The alchemist’s knowledge was, therefore, often compared to the creative power of God (for instance, in the 10th-century treatise Rutbat al-hakim, by Al-Majriti) and represented the highest level of knowledge attainable by humans. Yet Arabic alchemists were, for the most part, able to harmonize alchemical doctrines with Islam. The belief in a pure and absolute version of monotheism led Islamic theology to assume the existence of a single creator: according to classical Islamic philosophy, God is the creator of everything that exists and is the direct cause of every action that takes place in the sublunary world. Since only God can create a change—a fasl (differentia specifica, substantial difference)—alchemy, with its aim of changing the internal nature of metals and stones, could have been considered religiously unacceptable. In the 12th century, however, the alchemist Al-Tughra’i proposed an intriguing solution: since nothing can be created unless God wants it to be so, the alchemist simply prepares matter to receive the fasl God will bestow.

Perhaps because of alchemy’s association with divine knowledge, Arabic alchemical treatises persistently appeal to secrecy: alchemists should avoid the transmission of recipes to greedy people whose main aim is to obtain riches rather than wisdom. As would their European followers several centuries later, Arabic alchemists used rhetorical tricks to conceal the secrets of the art from the uninitiated. In the introductory essay to his translation of the first 10 books of Jabir ibn Hayyan’s Kitab al-sab‘in (The Book of the Seventy), Pierre Lory underlines the author’s habit of “scattering knowledge” (tabdid al-‘ilm) by intentionally presenting alchemical procedures out of order so that only the initiated could understand how to read the text. Alchemical authors used a highly enigmatic language, marked by abundant metaphors and technical and allusive terminology, to describe their processes and ingredients. Like the Hellenistic alchemists before them, the Arabic alchemists referred to a metal by the name of the planet that was thought to exert influence over it, so that recipes included Moon for silver, Mercury for quicksilver, Venus for copper, Sun for gold, Mars for iron, Jupiter for tin, and Saturn for lead. Modern readers must bear in mind that even when the names of the alchemical ingredients appear identical to those used in modern chemistry, they rarely designate the same substance.

Read more by Gabriele Ferrario: http://www.chemheritage.org/discover/media/magazine/articles/25-3-al-kimya-notes-on-arabic-alchemy.aspx?page=1

- 1954 reads