Submitted by SHABDA - Preceptor on

Submitted by SHABDA - Preceptor on

Harmony As The Goal Of The Universe

Anyone who is even slightly familiar with the theory of harmony knows that every dissonance tends towards becoming a harmony. If it is true that harmonic relationships in music reflect the harmonic and mathematical relationships in the planetary system as well as in the cosmos, the microcosm, the biosphere, and all the other fields we have talked about, then this rule must be valid also outside of music: All dissonances gravitate towards becoming harmonies. It would fill the pages of a thick book to carry out this thesis in all the different fields. Hence this chapter will limit itself to a small body of evidence.

Let us begin with music itself. Its history could be written from the viewpoint that music consists of the continuous discovery of new harmonies, of novel consonances and harmonic possibilities. In the beginning phase of man's perception of music, only monophonic melody lines were felt to be "euphonious." The first step toward developing harmonies was the discovery of the octave. In the Western world, this step was taken during the era of Hellenism, Its fundamentally new aspect was the possibility of connecting a tone of the melody line with another one and to experience this connection as harmonious. The next steps (still in late Hellenism and the early Middle Ages) were the discoveries of the fifth and fourth intervals. Throughout the Middle Ages, the third was considered to be a dissonant (even---according to medieval musicians---satanic) interval. The first natural thirds (and, by the way, also the first natural sixths, the reversed third) appear around the year 1300, mostly in love songs, for instance in Guillaume de Machaut's "Mirror of Narcissus," as well as in the songs of the troubadours of Provence in southern France. They were then considered avante-garde and gave rise to heated discussions. Today we hear the epitomy of conservative euphony.

In the course of the fifteenth century, the major scale won general recognition, first as the C modus, derived from the system of the old church scales, which contained all five "natural" consonances. Even today, the prominence of the major mode as opposed to the minor one usually is explained by the greater wealth of consonances in the major scales.

Staring with Johann Sebastian Bach, the entire development of Western music can be interpreted as increasingly intense (and successful ) search for consonances in those intervals and chords previously considered to be "unharmonious" and "dissonant." Again and again in this development, the line we drew in chapter 4 between the more consonant and the more dissonant sounds was crossed---even by Bach himself, with his fondness for chromaticism. In the nineteenth century, finally, only the intervals of the second and the seventh (above all the minor second and the major seventh)remained as "intervals of displeasure." Debussy found chromatic "consonance" even in these, particularly in the most critical of these intervals, the minor second. And the especially sticky tritone, the "flattened fifth," has become indispensable perhaps since late Beethoven, but certainly since Wagner. In his Craft of Musical Composition, Hindemith attributed a key position to it. The fact that it also holds a similar position in jazz, particularly since bebop, has already been mentioned. Modern concert music had reached a point in the 1950s, where composers felt that dissonances could be achieved only by so-called clusters (the simultaneous sounding of all tones across the entire keyboard). In a few years' time even these were turned into "euphonies" of sorts, for instance by the Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki, his German colleague Bernd-Aloisn Zimmerman and especially by Gyorgy Ligeti of Hungary in his compositions for organ. Ligeti's work Volumina is a truly touching example of iridescent beauty achievable by a series of minor seconds. Ligeti said about Volumina:

Chordism, configuration and polyphony have been obscured and suppressed, but underneath the sound surface of the composition they remain secretly effective as if they were deep below a water surface. . . .Figures without faces are created as in paintings by Chirico, immense expanses and distances, and architecture consisting of scaffolding only . . . . Everything else disappears in the wide empty spaces, in the "Volumina" of musical form.

Ever since the beginning of modern concert music, the question has been asked why, in all cultures where music plays a role (that is, in all cultures), the great musical creations limit themselves to a comparatively small arsenal of tones. In experiments made at the University of Illinois in Chicago, Richard Norton found the extent of the reservoir of tones that the human ear can clearly differentiate:

We found that, depending on the length of tone, on the time elapsed between hearing different tones and on the state of mental fatigue of the listeners, musicians and non-musicians alike were able to hear far more than one thousand "just noticeable differences" (JND's, as the experts in acoustics put it) between the lowest and the highest audible tones. Precise experimentation resulted in 1,378 "just noticeable differences" between these musically "raw tones."

The conclusion to be drawn from this simple but somewhat fatiguing experiment is that the human ear is an astounding sense organ whose potential has never been realized in music. Thinking of the music of the Western world as well as in other cultures, we realize that all of us, musicians and music lovers, are rather idle people when it comes to making music, considering the giant potential which the ear, in fact, has. Even the modern piano has only 88 keys which seem to be entirely satisfactory to both composers and listeners. What are eighty-eight tones (more or less) out of more than thirteen hundred? After thousands of years of human history, do we have to admit, with a certain amount of embarrassment, that we use only five per cent of the available tones when we make music? Why have we limited ourselves to the twelve tones of the chromatic scale, which we keep duplicating in so-called octaves in order to create that object, full of meaning and emotions, which we call music?

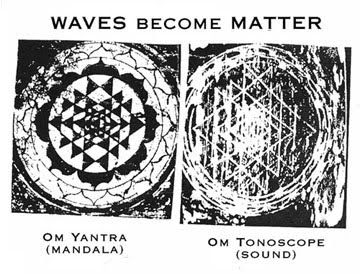

One of the answers to this question (as I have mentioned) lies in the hearing disposition of the human ear. The ear "prefers" whole-number relationships. Another (similar) answer results when we relate the "music" discussed in chapters 4 and 5 ( the "music" of the macrocosm and of the microcosm) to our human music. We are aware by now that music is more than music. It is cosmos and atomic microstructure, earth and stream, plant and leaf shape, human and animal body, to such an extent that the French-American composer and musicologist Dane Rudhyar was able to write: "The physical world of human experience resembles a giant sounding board." Everywhere on this board, this instrument with its truly cosmic dimensions, there are the same harmonic proportions. Precisely these proportions are the fountain of "music" in the narrower sense(the audible music of our human cultures) and define the arsenal of its tones. Whenever these tones are not struck exactly, they are "heard correctly" in the sense laid out at the end of chapter 5. Those areas not open to "corrective hearing" are excluded. That is the reason, Rudolf Haase has suggested, why the so-called quarter tones, which fall precisely into the gaps between the "areas of corrective hearing," have never been able to prevail in music.

What is tonality? Richard Norton answered: "Tonality is the decision against the chaos of tones created by those thirteen-hundred JND's we discovered in the acoustics lab."

That means, music is unthinkable without an act of choice. From the wealth of "possible" tones, from that which Norton calls the "chaos of tones," only few tones are chosen in order to prevent chaos, exactly those tones that exist also in the cosmos and in the organic forms of nature. It is the same act of choice that we heard about in chapter 4 as a perogative of mind and spirit.

This "act of choice" can also be referred to, with an expression taken from nuclear physics, as "quantizing." We (nature, spirit, mind) choose in quanta. This, too, becomes apparent on the mono chord and in the overtone scale. When the finger slides upward on the string, a preference of certain tones is sounded: "Nature itself makes a choice. The tones jump from one to the other, so to speak. They are not a part of a continuum but rather a series of quanta." Kayser points out that the same thing happens on a valveless horn. "It is very difficult for the player to produce pure intermediate tones. In reality, the tones jump from the basic tone to the octave, then to the fifth, then again to the octave, etc." Thus nature does not do "what we want but what it wants. I can slide up or down with my finger as carefully as I want to, if it strikes a spot where the string ' doesn't want it,' the effort is in vain. Thus it is obvious that nature makes a choice or, to put it another way, that it 'creates norms.'"

Kayser also points out that Max Planck, the founder of quantum mechanics in modern theoretical physics, did extensive research on the mono chord and problems of acoustics. In an essay published in 1893 entitled "Die naturliche Stimmung in der modernen Vokalmusik" (Natural Tuning in Modern Vocal Music), Planck wrote:

According to the postulate of quantization, the discrete intrinsic values of energy lead to certain discreet intrinsic values of the period of vibration. This happens in the same way on a tense string fastened at both ends. The difference between them is that on the string the quantization is conditional on an exterior factor, the length of the string, where here it is conditional on the quantum of energy resulting from the differential equation itself.

Wilfried Kruger (to round out the picture) even succeeded in finding a basis for tempered tuning in nuclear physics. The question as to which of the different possible tunings is the correct one has a long history. It has become customary to look down upon the "equal temperament" as something "artificial" and "violent" and "mathematically constructed." The basic idea of tempered tuning, however, lies in the division of tonal space into identical subspaces. This corresponds to Planck's quantum mechanics, according to which effects can be produced only as a multiple of a smallest unit no longer open to further division. Thus, the "quantum mechanics" of the microcosm correspond to the "quantum harmonics" of equal temperament. "The tonal space, in actuality, is an atomic space."

Only through tempered tuning was the miracle of modulation possible. Only through it are transpositions easily executed (and we have already learned that the possibility of transpositions exists everywhere in the universe). Above all, though, only after the introduction of equal temperament in the seventeenth century began that true musical explosion, that immense boom of music in the Western world that numbers among the greatest phenomena in the cultural history of humankind.

It is important to realize that the tendency toward harmony, immanent in music, in a way is nothing else but a reflection of the same tendency outside of music, in almost all fields. As George Leonard notes: "In 1665 the Dutch scientist Christian Huygens noticed that two pendulum clocks, mounted side by side on a wall, would swing together in precise rhythm. They would hold their mutual beat, in fact, far beyond their capacity to be matched in mechanical accuracy. It was as if they 'wanted' to keep time."

Science has taught us that this phenomenon is universal. Two oscillators pulsating in the same field in almost identical rhythm will tend to "lock in," with the result that eventually their vibrations will become precisely synchronous. This phenomenon is referred to as "mutual phase-locking" or "entrainment." Entrainment is universal in nature. In fact, it is so ubiquitous that we hardly notice it, "as with the air we breathe," as Leonard put it. It is a physical phenomenon, but it also is more than that, because it informs us about the tendency of everything that vibrates --- in other words, everything-to swing together, to lock in. It informs us about the tendency of the universe to share rhythms, that is, to vibrate in harmony. Leonard continues:

To get the feel of entrainment, you might try playing with the "vertical" and "horizontal" knobs of an old television set. Every set contains horizontal and vertical oscillators that position the scanning electronic dot that forms the picture. These oscillators must match the signal coming from the station very precisely; otherwise the picture will move sideways or vertically. Fortunately, you don't have to create a perfect match. When the frequencies come close to one another, they suddenly lock, as if they "want" to pulse together....

Living things are like television sets in that they contain oscillators. In fact, we might say that living things are oscillators; that is, they pulse or change rhythmically....There is an electrifying moment in the film "The Incredible Machine" in which two individual muscle cells from the heart are seen through a microscope. Each is pulsing with its own separate rhythm. Then they move closer together. Even before they touch, there is a sudden shift in the rhythm, and they are pulsing together, perfectly synchronized.

The Boston scientist William Condon has shown that this "harmonization" or "entrainment" also takes place when two people have a good conversation. All of a sudden, their brain waves will oscillate synchronously. In fact, Condon was able to show that the brain waves of students listening to their professor's lecture will largely oscillate "in harmony" with those of the lecturer. Only when this takes place do those present perceive the atmosphere in the lecture hall as "good."

George Leonard found an especially impressive example of such entrainment in the relationship between preachers and their audiences, particularly in the sermons and addresses of prominent pastors, as for instance Martin Luther King, Jr. A sermon is perceived as "successful," "electrifying," or "exciting" only when the brain waves of the members of the audience vibrate synchronously with those of the preacher.

Similar observations were made between mothers and their children, husbands and wives--in short, the most diverse groups of individuals for whom harmony is a goal.

Another scientist, Paul Beyers of Columbia University, documented on film and analyzed human interaction in greatly varying cultures---those of Americans, Eskimos, African Bushmen and New Guinea Aborigines. In each case, he found rhythm sharing. Byers wrote: "Synchronized heartbeats have been reported between psychiatrist and patient. Female college roommates sometimes find their menstrual cycles synchronized."

As Leonard points out:

In music, the miracle of entrainment is made explicit. The performer's every gesture, every micromovement, must be perfectly entrained with the pulse of the music, or else the performance falls apart. Watch the members of a chamber group---how they move as one, become as one, a single field. We have become accustomed to such miracles: the extraordinary faculty of jazz musicians to "predict" precise pitch and pattern during improvisation....The miracle springs not so much from individual virtuosity...as from the ability of a large group of human beings....to sense, feel, and move as one.

This tendency to feel and move as one can also be observed among large flocks of birds or schools of fish. The flock or school is constantly changing, yet it remains miraculously well ordered, its form still "harmonious." For decades, Western functionalistic-mechanistic thinking led science to assume that large flocks must have a "leader." Today we know that "alpha animals" exist only when two or three birds or fish fly or swim together. When the number of fish or birds becomes larger, the group itself becomes a "being." Professor Brian L. Partridge of the University of Miami, a specialist in the behavior of animals in large groups, wrote that "in a certain sense, the entire school is the leader, each individual being part of the followers." The group is " more like a single organism than an accumulation of individuals....In all probability, it is as if each member of the school knows where the others are going to move....The fact that they never collide is fits this hypothesis." The commands come from the group as a whole, not from a single animal. In this sense, the group is the "being"; and in this way people close to nature have always seen large flocks of birds, as one "being" moving in the sky in constant change and yet "keeping in form."

It is highly interesting in this context that collisions are, in fact, very rare occurrences in nature. Compared with the frequency of collisions among human beings, they are surprisingly infrequent, even in much denser populations, as in the bustle of an anthill, the termite nest or a beehive, in compact cultures of bacteria, in the blood vessels of humans or other mammals, or in compact flocks of birds, which are able to change direction all at once even while flying at high speeds. So rare is the occurrence of collision that we may conclude that "collision" is largely a human phenomenon. We have "unlearned" to feel (that is, do not listen to)the "harmonization" and "entrainment" of our own "flocks" or "schools." Possibly this has to do with the fact that in many instances human behavior is largely controlled by the rational left-brain hemisphere.

Resonance phenomena, entrainment, and related phenomena have been discovered in the most diverse fields, in architecture, in electronics and acoustics, in psychology and psychotherapy, in biology and chemistry, in medicine and pharmacology, in physics and astronomy.

Entering into harmonic relationships is the goal not only of music. It is the goal of atoms and molecules, of planetary orbits, of cells and hearts, of brain waves and movements, of flocks of birds and schools of fish and---in principle---of human beings. All of them (or better:the cosmos, the entire creation) have harmony as their final goal. They are all moving to realize Nada Brahma.

The phenomena of entrainment and synchronic discussed in the present and fifth chapter can also be understood in terms of rhythm. Rhythm is "harmony in time." Rhythm and harmony complement each other. The inclination toward rhythm includes the inclination toward harmony.

Gunther Hildebrandt of the Institute for Ergophysiology at the University of Marburg writes: "The human organism is not only constructed according to harmonic principles but also functions with them." Similarly, Haase explains: "It has been found that the rhythmics of the human organism function utterly harmonically---that is, the frequencies of pulse, breathing, blood circulation, etc., as well as their combined activities. We can observe that these rhythms are strictly coordinated, primarily in terms of the numbers one through four, which are able to form the intervals octave (1:2), fifth (2:3), fourth (3:4), twelfth (1:3), and double octave (1:4)."

As Haase points out, interrupting these rhythms with their whole-number proportions causes illness in the human body. "Particularly in cancer cases we observe a total irregularity of all rhythms. Apparently the cancer cell causes a withdrawal from the temporal harmony of the body functions."

Haase, too, refers to rhythm as "temporal harmony." In the final analysis. it is a matter of interpretation whether we experience the numerical proportions that are found in so many phenomena of the organic and inorganic world as harmony or as rhythm. Harmony is rhythm is harmony is rhythm.

Rudolph Haase's description of cancer as a state of "rhythmic chaos" touches upon another important point. The cancer phenomenon ought to be seen against the background of the fact that any individual cancer is only part of a much more encompassing cancerous disease that we encounter throughout the modern world, in society, urbanization, economy, ecology, politics, in the military arms race, the medical system, and dozens of other fields. Cancerous growth is a state of mind. Since it takes place in the head, it causes new processes of cancerous proliferation in all areas affected by human consciousness. Anyone who has seen Lagos, Sao Paulo, Mexico City, Calcutta, or Tokyo is familiar with the phenomenon of cancerous urban growth, for example. Yet this is a problem that is limited neither to the Third World nor to large cities. Examples can be found in smaller communities as well---say, an American town such as...but I hesitate to write the name of the town i was thinking of, because there are people living there, human beings, to whom I would be saying: You are living in the middle of a cancerous ulcer. For we have the same attitude toward cancerlike growth in public life as toward the physical disease: we try not to talk about it.

On any transcontinental flight you can see how the cancerlike spread of cities and suburbs, of industrial parks and projects has seized the earth like an epidemic. It is like a scabby white crust creeping over what remains of our green land.

Even more obvious are cancer phenomena in the field of economics. World economy in the 1970s and 1980s has literally been dominated by them. That is why the tried-and-true economic systems have failed and why, in almost all cases, the prognoses of even the most experienced experts and scholars in economics and politics have turned out to be wrong. Processes that according to our conventional causal concepts should exclude each other are coupling together to produce novel combinations such as growing industrial investments plus simultaneous mass unemployment. Or declining capital flow along with growing inflation. Or simultaneous economic growth and recession. Precisely this is the nature of malign proliferation: it can be neither controlled nor predicted. It simply grows wild.

Cancerous growth is a problem also in the political and administrative apparatus, as anyone will recognize who has read about the giant bureaucracies in the capitals of the West (and the East!), from the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., to the Common Market Center in Brussels to the KGB Headquarters in Moscow. Departments constantly create new departments, subdepartments keep splitting into ever new offices and special divisions that question one another's existence, go to war with one another, cancel one another out so that not even the chiefs of staff really understand the administrative structure of their outfit -- which in turn drives them to invent new structures, departments, divisions and ---"cells." All we have to do is exchange a few words, and the description of the bureaucratic cancer turns into a description of cancerous growth in the human body.

The same is true about administration in industry. In large companies, you often find that the central administration is opposed by administrative apparatuses of the company's various subdivisions. In this situation, communication would seem to be of utmost importance. In reality, however, communication is replaced by a flood of paper, by forms to be filled out. Often enough, division chiefs, department heads, administrative personnel, and secretaries spend more of their time filling out forms than doing their actual work---forms that frequently disappear in somebody's files as quickly as they are completed. Computer-written documents and graphs, whose language and system most people fail to understand, wander from one desk to another as if they possessed a life of their own, as if they were ghosts. Insiders exchange knowing glances: Just write anything, it doesn't matter; don't worry, we don't understand it either. And they all know that the really important processes, which most of them want to keep going in spite of everything, are self-controlled, and that with a little bit of common sense you somehow make it. What I have described here is precisely the struggle between the uncontrolled wild growth and the core of health that is characteristic of the clinical picture of cancer.

Almost anyone who is a part of contemporary professional life is familiar with such processes of cancerous growth. The disease of cancer exists not only in the human body. It exists everywhere. Which means it is impossible to overcome it as long as we fight against it only in the human body. Let us remember our description of cybernetic networks. There is an entire network of causes for cancer that goes far beyond the field of medicine into the sphere of consciousness. The school of medicine that is stuck in the causal thinking of the nineteenth century (the belief that there is one and only one cause for any particular illness) is unable to solve the problem, as we know by now. We need to concentrate on the network --- not only the network of cancerous cells in the human body but also the cancerous network in our consciousness. The formation of chaotic rhythms.

I previously noted the poet Novalis: "Every disease is a musical problem." The realization that cancer has to do with malfunctions of rhythm, resonance, vibration, and harmonic "tuning" is not only an aesthetic-philosophical finding. It is a discovery in line with the state of the art in modern cybernetics.

"Harmony as the Goal of the Universe": the seven words that form the title of this chapter have to do with a teleological (from Greek telos, "goal")idea, with the idea of finality. Harmony is the goal. In order to reach this goal, harmony has to grow. We began our deliberations in chapter 4 with harmonic structure of our planetary system as discovered by Johannes Kepler. Already that context made clear that structure is a goal. Whatever theory one adheres to about the genesis of our solar system, one thing is obvious: the planets, whether they were pulled in by the sun or cast out into space by the prime mass of the sun or "bred in the primal cosmic broth," cannot have been revolving around the sun in harmonic orbits from the beginning. They must have "found" these orbits after millions or billions of years. Which means, the harmony of the orbits was a (finally reached) goal. This is what is so extraordinary---that in spite of billions of possibilities, the goal was reached with such remarkable determination.

Let us return to the discipline from which the word harmony takes its primary meaning, to music. We have seen that harmonies had to be "discovered." This took hundreds of years during which different musical and harmonic systems were found, kept for awhile, and discarded, until (around the time of Bach) the system was reached that today is largely considered to be the valid "occidental" system. From this point of view it can be seen as "goal." Almost all cultures and peoples tend to adopt it as a whole or at least in part as soon as their musicians become familiar with it. It is often said that this is an undesirable process of "Westernization" or even "Americanization" in the wake of American pop music. At first glance this may be so, but at the core of the matter there is something quite different. The musicians (and the ears) of the world experience the teleological nature of the Western system of harmony. They have no problem doing this, because the crucial characteristics of this system are embedded like "germ cells" in all music of all people.

Let's look at the word germ for a moment. There is nothing harmonic in germs, seeds, or sprouts. The plant has first to develop before its harmonic beauty reveals itself to our eyes, in the leaf shapes and in the blossoms. The growing process of a plant from germ to fruition is a constant reminder that harmony is a goal to be reached.

Part of the idea of a goal is consistency. One reaches a goal, and then one stays there, at least long enough to decide on a new goal. In the periodic table of elements, those elements are least consistent and stable that have a surplus of protons and neutrons. Harmonically, this "surplus" means that the particular elements possess particles that do not (or very fragmentally) fit into the harmonic overall structure of the system. It is as if they have too many "particle tones" that are "alien to the scale" and "alien to the major triad." Therefore they decay in radioactive processes, aiming for a different, more stable state. Their state becomes "more stable" when it becomes "more harmonic." The less harmonic these elements are (for instance, plutonium, uranium, actinium, thorium), the more radioactive they will be, which also means, the more dangerous they are for man. The smaller the "harmony" of the atomic structure, the greater the danger for life. This is similar to what we discovered about cancer. By the end of the present chapter we will see what truly astonishing consequences the idea of harmonic finality can have. Before continuing with this train of thought, however, we must consider the opposite force: entropy.

In opposition to harmonization as the goal of the universe stands the second law of thermodynamics. In brief, it states that what develops is not harmony (structure, order, differentiation) but quite the opposite, disorder and chaos: entropy. Entropy therefore seems to characterize the final state toward which the universe is developing, its death in the lowest energy state possible, its "caloric death" and sinking into an undifferentiated "caloric soup."

More and more frequently, however, science has been confronted with the question why---if entropy develops so irresistibly---the final state of general chaos was not reached long ago. In fact, certain theoretical models suggest that it should have been reached millions of years ago. Biologists in particular have become quite outspoken opponents of thermodynamics. For a long time---indeed, until Prigogine solved the problem---it was difficult to combine the findings of evolution (the "simple" fact that life exists and is in a continual process of differentiation and development) with entropy.

In the work of Jean E. Charon, an important role is played by so-called negentropy. Entropy as we said, means the disintegration of order and differentiation. Negentropy, however, negative entropy, is the cosmic force opposed to entropy. It holds the promise of increasing order and differentiation, of a constant development not only of life but of the entire universe, of the microcosm as well as the macrocosm.

For Charon the electron is to the microcosm what the black hole is to astrophysics. Both the electron and the black hole are characterized by totally curved space and by curved time. This means that the time of electrons and of black holes is opposite to our "material" time, which moves on a straight line from past to present to future. This, in turn, may imply that if entropy grows in the "material" world, then in the world of electrons (and black holes) precisely the opposite force might grow, the force of negentropy. This, then, could be the place where order and differentiation are on the increase, where the principle of development toward a higher state is valid (which, in the final analysis, is development toward a higher state of consciousness).

Until recently it was believed that the development of negentropy was characteristic of life. No doubt negentropy is a principle in the cell, in genes and DNA molecules. Now, however, there seems to be evidence that this expansion is a much more encompassing principle, a principle of electrons and photons. In no way can it be limited to the sphere of life. Charon writes:

Only when one has understood and accepted this standpoint, one begins to realize how the spiritual standard of the entire cosmos is progressively on the upgrade. This takes place by the primal matter passing through many successive "life experiences." For more or less extended time periods, the primal matter will be part of mineral matter, then of living or even of thinking creatures. All the information stored in the course of these successive life-experiences cannot be lost.

The evolutionary tendency of electrons is analogous to that of human beings. Whatever our cultural and educational background may be, all of us feel that our lives become "better" the more we devote it to the source of cognition and love. In this sense, we have been "programmed" by evolution. To be sure, I should not have used the word "analogous." There is no "analogy" when you look at things precisely. We are our electrons. Charon: "My thinking is the thinking of my electrons. It is not merely analogy but identity."

The electronic "prime matrix" (the space within an electron) can be imagined as a honeycomb. Each cell of a honeycomb is either "empty" or contains a photon---with the characteristic inclination to reach higher spin states. The fact that electrons, as microcosmic particles, are smaller in size than we can imagine does not speak against their unimaginably large capacity for information storage. Consider how dense matter is inside an electron. We have learned that it is similar to the density of black holes, that is, to the mass of the sun concentrated in an object about 3.5 to 6 miles wide. Also consider their temperature---millions or even billions of degrees. Besides, nothing is really imaginable. The honeycomb is just an auxiliary concept. No structure is conceivable in curved space that would make any sense in the spatial context of our human three-dimensional space. The honeycomb cells would have to be packed much more densely, in a manner more complex and more complicated than would ever be possible in a beehive. One more reason for the immense information storage capacity of the electron is the fact that photons have zero mass. In other words, the number of photons in an electron is almost unlimited since the mass of the electron is so incredibly dense.

Think of the number of electrons we have talked about. A simple computation made by Charon shows that even in this moment, toward the end of the twentieth century, each one of us, with each breath we take, exhales or inhales a few dozen of the same electrons that Julius Caesar expelled with his last sigh at the moment of his assassination in 44 B.C.E. Our assumption that an electron stores everything that has taken place since the beginning of the universe does not just apply to some random electrons way out in the depth of cosmic space. A few of these "oldest" electrons are in each one of us. And each one of us, therefore---the repetition is intentional---has electrons that have been part of Jesus or the Buddha or other great saints and seers in history, electrons that are charged with their photon information, their photon cognition, their photon love. In each one of us, on the other hand, are also electrons that have been in (and are thus programmed by) people like Hitler and Stalin, Himmler and Eichmann and other arch-criminals of mankind. Indeed, even from this vantage point we seem to be headed toward the realization of the seers and wise men of Asia and Egypt that everything is in us---the same realization that is suggested by modern theoretical physics, holography, and the other phenomena we have discussed.

To stretch our imagination even further: Each particle---each of the millions of "matrix boxes"---has its own spin, and all these spins vibrate together in the whole-number proportions of the overtone scale. This, then, is the prime model of mind and spirit, the prime model of "cognition," "reflection," "deed," and "love": an enormous chord, a chord that is "tuned" to the "keynote" of Max Planck's energy quantum.

Negentropy, the counterforce of entropy, increases not only because the spin matrices of the electrons become more and more differentiated through "cognition," "reflection," "deed," and "love." It also increases insofar as the number of black holes (and also, following certain theories, the number of electrons in the cosmos) constantly increases. For a long time now, astronomers have felt that the black holes with their temporal progression running counter to entropy are becoming more and more numerous in the course of the history of the universe. Their appearance is one characteristic indicating a late stage of development. In fact, according to one cosmological theory, everything in the vicinity of a black hole ---close enough to be attracted by it---will disappear from this world forever, only to reappear in a "counterworld." Thus, a black hole can be seen as an embryo of a new universe. A universe of negentropy? of spirit?

The following cosmological model now moves into the range of the possible: Each spin state can be interpreted as a tone of an overtone scale.Each spin contains all prior whole-number spins, as each tone of an overtone scale contains all other tones. According to the cosmological model of the " complex theory of relativity," it is conceivable that only at the end of time (Charon has computed that this state will come in approximately 20 billion years) will all spins have reached their highest spin state. And just that is the process of differentiation and development: the higher the spin, the higher the state of consciousness. To be sure, there are particles of the highest category even today, but they are rare. In this way, we have found a new interpretation of evolution: The further it progresses, the more spins will reach the highest point of their development. The endpoint of evolution will be achieved when all spins have reached this highest level. What the French philosopher and anthropologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin called the "Omega point," the attainment of the highest cosmic consciousness---could it be understood as a harmonic process? Note the quotation marks. It is too early to postulate all this, but we must ask the question, since certain findings of particle physics point in exactly that direction.

Again and again I have used the expression harmonic. Originally, we all understood it in the context of harmonics in music, of the laws of overtones. But have we not come to a point now (if we weren't already there at the end of chapter 4) where we must differentiate the term harmonic? The entire cosmos, reaching to the depths of pulsars and black holes, the subatomic world down to the electrons and photons, the world in which we live, leaves of plants, animal and human bodies, and minerals---is all that supposed to be structured according to the laws of the musical theory of harmony and to swing by them? Must we not assume that things are exactly the other way around, that harmonics in music were formed according to the structural laws of our world, of the macrocosm and the microcosm? Do expressions like harmonic or overtone scale not have a narrowing effect, limiting things too much to the field of music? No doubt the word harmonic has to be understood, in the sense of this chapter, not merely as the fact that the world is structured according to the musical theory of harmony, but rather as an increase in harmony of the entire cosmos. This is to take the word harmony in its widest sense, encompassing the "harmonious" relationship that are desirable between all human beings as well as musical "harmonics" or the "harmonics" of the spin of particles. This understanding makes "harmony" (for example, that between humans) a task for all of us. The more we obey this command, the more decisively will we be on our way to the "goal" that is the theme of this chapter, to a "finale" (another musical expression) of truly cosmic-musical dimensions.

More than once in this book, we have referred to age-old wisdom of Asia that "Everything is One." Or, as it is stated in the Upanishads:"The spirit down here in man and the spirit up there in the sun in reality are only one spirit, and there is no other one." The harmonic structure of the universe---in the final analysis, what is expressed by the words Nada Brahma---may well be the most striking and convincing indicator for the unity of the world that we inquiring human beings, with our limited perception, can find. Beyond that, there is only one path, the path pointed out by the seers of the East and of mysticism: to experience the unity itself, to hear Nada Brahma Itself.

"When you blot out sense and sound, what do you hear?" You hear primal sound, you hear Nada Brahma. at some point in time, somewhere along the path to the goal you will hear It. We have found that Nada Brahma is there, even from the viewpoint of Western rationalistic science. Doesn't there have to be some sort of sensory apparatus that is able to perceive all these sounds permeating the universe? For what other reason would they exist? Music is inevitably made for ears, even if it is meant for ears beyond the two fleshy extensions on either side of the human head. Our "ears" (note the quotation marks) must transcend their limits, because the "music" we have been talking about is also transcendent. "He that hath ears to hear, let him hear" (Matthew 11:15).

- 6981 reads