Submitted by Striker on

Submitted by Striker on

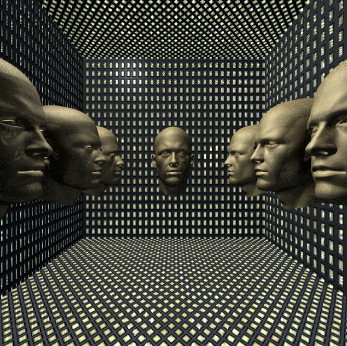

Automata and artificial intelligence ...

“The human being is a self-propelled automaton entirely under the control of external influences. Willful and predetermined though they appear, his actions are governed not from within, but from without. He is like a float tossed about by the waves of a turbulent sea” – Nikola Tesla

Why create artificial intelligence? We don’t want to work and we don’t want to die, but more than that, we want answers to life’s mysteries, the most elusive of those mysteries being our own consciousness. More than a perfectly rational decision-making engine we want a salve for our existential insecurity. Through the course of human history, we have envisioned ways to construct a superintelligence that would remove our uncertainty. Is it not curious that whenever we conceptualize an intelligence superior to our own and do not endow it with divinity, we divorce it from the body? Trapped in our fragile shells, tormented by the pain of existence as a physical organism, we long for the purity of thought we imagine could only reside in a “talking head”, be it the brazen heads of the alchemists, the dream of an artificial brain, or the cable network news analyst. We regard the body as a trap for reason, subject as it is to those pesky biological imperatives. Our senses fool us. We’re guided by our heart’s passions. Our thirst and hunger drive us to madness. But the talking head eschews these worldly concerns, has no wants and needs, rather exists only to be an oracle.

The head is traditionally the seat of wisdom. At the end of the mythological Norse Æsir-Vanir War, a hostage exchange goes sideways, and the Vanir wind up beheading an Æsir negotiator named Mímir, sending his head back Asgard. Odin did a little Teutonic magic, and preserved Mímir’s head so he could continue to consult him as a trusted and knowledgeable advisor. Presumably labor laws now prevent this kind of exploitation. Before his unfortunate decapitation, Mímir was considered a fount of wisdom, but after, the head alone was credited with the revelatory abilities and the possession of information about other worlds. 12-13th Century Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla (Chronicle of the Kings of Norway), describes the technical process by which Odin prepared Mímir’s noggin’ for employment. “Odin took the head, smeared it with herbs so that it should not rot, and sang incantations over it. Thereby he gave it the power that it spoke to him, and discovered to him many secrets” (Sturluson, 1844, p218-219).

Pope Sylvester II (946-1003 A.D.), originally known as Gerbert of Aurillac, had a lot of scholarly talents, from astronomy to mathematics, introduced the decimal numeral system to Europe, reintroduced the abacus, and just so happened to be the first French pope. Another of Gerbert’s many claims to fame was his reputed creation of a brazen head, instructions which he found in a stolen secret tome from Moor-occupied Spain. “He cast, for his own purposes, the head of a statue, by a certain inspection of the stars when all the planets were about to begin their courses, which spake not unless spoken to, but then pronounced the truth, either in the affirmative or negative” (William of Malmesbury, 1889, p181). Now, I’m reasonably impressed with any fellow who can make a metal head that answers questions, but one of the common threads that reappears in the alchemists’ and sorcerers’ dabblings in brazen heads is that the head knows the truth. It’s why you create it after all.

After Gerbert, the list of brazen head makers is long and includes the Roman poet Virgil, English scholar Robert Grosseteste, Doctor of the Church Albertus Magnus (Thomas Aquinas, his student, was said to have destroyed it when it wouldn’t shut up and was interfering with his concentration), philosopher and theologian Boethius, alchemist Johann Georg Faust, physician and astrologer Arnaldus de Villa Nova, and “Doctor Mirabilis” himself, Friar Roger Bacon, who reportedly created his brazen head with the express purpose of asking it whether it made sense to make Britain impregnable by ringing it with a wall of brass. A bold, and likely cost-prohibitive maneuver, but what price freedom, eh? Unfortunately, Bacon and his fellow engineers were so exhausted from constructing the head that they supposedly fell asleep and missed the decisive answer. Apparently, brazen heads do not like to repeat themselves.

We’ve been constructing bodiless intelligences for at least a thousand years now, hoping to hit upon that particular combination that reveals the meaning of life, and I suspect our latest obsession with creating artificial intelligence is likely just the latest reflection of this crusade. Perhaps we wouldn’t mind smart cars, smart agents, smart refrigerators, mechanical chess masters, Jeopardy winners, and free-thinking robo-servants/soldiers/adult toys to keep us company in this lonely universe, where we’ve seen no other signs of intelligent life, but deep down we figure if we can create a conscious mind not dissimilar to our own, but faster and free from our worldly cares, are we not gods? And shouldn’t gods have prophets? Talk about tautological theology. We’re not sure about the existence of the gods anymore, and consequently we have to make our own oracles, just in case they never get around to answering our prayers or explaining themselves. As David Byrne of Talking Heads fame said, “Patience is a virtue, but I don’t have the time”.

References

Snorri Sturluson, 1179?-1241. The Heimskringla. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1844 ed.

William, of Malmesbury, approximately 1090-1143. William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the Kings of England: From the Earliest Period to the Reign of King Stephen. London: G. Bell, 1889.

Read more at https://esoterx.com/2016/06/13/talking-heads-automata-and-artificial-intelligence/

- 1100 reads